Doctor reflects on fear and panic of pandemic’s initial days in El Salvador hospital

With many of the initial COVID-19 cases, patients did not receive humane treatment because panic and dread took over. One can judge and say the medical teams involved are bad, neglectful people; however, fear blinded them.

- 4 years ago

March 23, 2022

SAN SALVADOR, El Salvador—All my life I wanted to be a doctor. It seemed to me like a way to help others without needing great means.

If I were born a thousand times, without hesitation, I would always study medicine. I would choose it even knowing what I would experience during the last two years of the COVID-19 pandemic.

As someone with lupus, diabetes, and hypertension, I was the perfect candidate to stay at home during the pandemic.

Though I know no one is indispensable, I also knew they would need my help as an epidemiologist. I know how to use the protection tools to deal with the virus, and the government channeled resources through me to prevent the spread of COVID-19. Therefore, I decided to stay to help.

COVID-19 comes to El Salvador, and we are unprepared

The first four months of the pandemic were terrible.

One of the things I remember most from spring 2020 was the great flow of misinformation prevailing both outside and inside the hospital. Uncertainty about whether the virus had already entered El Salvador loomed over every conversation between the medical staff.

These rumors upset and scared people, but our lack of resources within the hospital and our great ignorance around the virus caused my colleagues the most concern.

All the information passed through my hand; the tremendous pressure of this responsibility weighed me down.

When officials finally confirmed the first COVID-19 case within the country, it cemented an atmosphere of fear and to a certain extent, dejection, at work. I heard comments asking how we were supposed to protect ourselves, protesting that we weren’t prepared and even stating that they would refuse to treat COVID patients without the proper gear.

The responses reflected people’s anxiety more than a desire to actually protect themselves. Other times, they overreacted, acting like the virus could spread through visual contact alone. It made me feel like they didn’t actually believe or respect the safety guidelines I announced, and like I didn’t have enough authority to push back on these incorrect assumptions.

The first case that tested positive inside the hospital was a senior physiotherapy student. I was the one in charge of breaking the news to her. I felt like crying when I saw her sitting in my office—she reminded me so much of my daughter.

At that time, we only had 12 biosafety suits for the entire hospital. We used bleach to disinfect facilities and utensils that came into contact with an infected patient. We resorted to creating our own biosafety gear; at one point, I made around 100 plastic aprons for the cause.

Likewise, we did not have fans, something that greatly affected both patients and doctors due to the hot, humid climate in El Salvador. The hospital also had inadequate space to care for people infected with the virus.

Hospital beds dwindle as patients increase

When I treated the first case of COVID-19, I was afraid but felt confident that nothing and no one could take my life apart from God.

Approximately 22 days after treating the first patient infected with the virus and requesting more resources from the Ministry of Health, we received more equipment to care for patients and protect medical staff. However, it was still not enough.

We initially sent critical COVID-19 patients to a different hospital, but it eventually collapsed and stopped receiving new patients. We then had to admit these critical cases ourselves.

The number of patients with Covid-19 began to increase, and soon we ran out of hospital beds. People were forced to wait for care in the corridors, then wheelchairs. Eventually even those ran out. It reached a point where we were helping people in the parking lots.

We worked hard so no one was left on the ground. We all experienced terrible and painful moments, doctors and patients alike; no medical professional wants to not be able to offer all the comforts a person deserves in times of sickness.

Isolation causes anguish as patient deaths rise

At the same time, our rate of patient deaths rose accordingly. We had only a small area for holding deceased patients, and it filled quickly. With no more space available, many corpses were left outside. It was terrible.

The hospital didn’t allow family members to identify their deceased loved ones; we just sent them directly to the cemetery.

One of the most painful moments for me was having to deny family members from seeing their loved ones. On one heart-rending occasion, a 38-year-old woman arrived, crying and begging me to see her husband. I started crying myself, but I couldn’t let her see him.

Though we are trained to see patients die, we do not get used to it. That would mean we stopped being human.

‘Blinded by fear’ while trying to care for COVID-19 patients

With many of the initial COVID-19 cases, patients did not receive humane treatment because panic and dread took over. One can judge and say the medical teams involved are bad, neglectful people; however, fear blinded them.

When the first COVID-19 case appeared, it was part of my duties to decide how to handle it at the hospital; how we should treat a patient suspected to have the virus when they arrived. However, some of my colleagues did not want to assume their responsibility of caring for these people. We often had to pressure them to do their jobs. No one wanted to get involved because they were afraid. Fear dogged my every step as well, but I knew my duty.

Many doctors and nurses rented a house together so as not to put their families at risk while caring for the influx of COVID-19 patients. However, I lived in a house where everyone was a doctor: my daughter is a gynecologist, my husband is an epidemiologist from another hospital, and my sister worked in a medical unit.

At one point, my daughter was admitted to another hospital for suspected COVID-19. She and other patients were locked in a ward with the windows closed. All this, because the staff feared the virus infecting them too. My daughter, being in healthcare herself, treated her fellow patients even as a patient herself. People were dying, but medical personnel never came to help.

When I had to go to work knowing my daughter was hospitalized, I felt overwhelmed and so worried that she could die at any moment. Adding to my distress, I was the first person at my hospital who had a family member with suspected COVID-19; I began to feel rejection and discrimination in my job, and colleagues even branded me as irresponsible.

Paradoxically, many colleagues didn’t follow basic biosafety guidelines, despite their worries about being infected.

Transporting an infected patient in an ambulance can be very suffocating; considering the enclosed vehicle and airtight protective suit, the hot, tropical climate only added to the discomfort. As a result, some medical personnel took off their suit too quickly and without taking care to prevent infection.

These initial months were exhausting and laborious—I felt like they took years off my life.

Transforming from doctor to patient

Eventually the medical staff began to get infected, and I was one of them. I thank God the health system was more organized and prepared by the time when I got sick.

My first symptom was a fever and fatigue. I decided to take an X-ray discovered I had mild pneumonia.

One day at 3 a.m., my daughter woke me up and told me I was breathing irregularly and that she was taking me to the hospital.

They took care of me right away. I was in a very bad state at the time; pneumonia filled both my lungs, and my glucose levels were unbalanced. Luckily, thanks to the fact that days before I had increased my dose of steroids, I did not feel seriously ill.

The hospital treated me as a suspected COVID-19 patient, and three days later, I tested positive. They admitted me to a room where there were 5 men—I was the only woman.

My fellow patients were in critical situations. They had oxygen at 10 liters per minute, but still they complained they wanted more air. I watched as they suffocated. Meanwhile, they gave me 3 liters of oxygen per minute, which was enough for me.

That room was air-conditioned and super icy cold, to hamper viral growth. They placed a very thin sheet on me, which barely covered me but still warmed me up.

While admitted, I had lots of time to think. I thanked God that my children were grown up and had careers, and that I had already paid for my house.

Feeling I had nothing to live for, I just waited for the will of God.

Forever changed by brush with COVID-19

Though I was ill, one just doesn’t stop being a doctor. Each oxygen tank only lasted 2 hours, and every time I saw that one of my roommates was about to run out, I went out to call the nurse.

When someone in our room died, the nurses slowly removed the bodies so that we wouldn’t listen and become scared. But as a doctor, I knew what was happening.

Even though we were dying, we all still ate. I often looked out the window and to raise the spirits of my roommates, I always announced when the food cart was coming. But on one occasion, because we were distracted by eating, we did not realize that one of us had died.

The doctors prayed the Our Father to us every morning. It is always good to remember the greatness of God.

Nothing is worth more than life. Nothing is worth more than being with your parents, children, wife, or husband. Sometimes we make life bitter for little things; we complain because the food is cold or too hot. When you are between life and death, you do not remember if you have curly or straight hair or are tall or small.

Though I recovered from my illness, I feel it has forever changed me. No one who has been through this pandemic can remain the same.

Embracing a new way of doing things

Now, two years into the pandemic, things have changed for the better.

We are well organized and have enough biosafety supplies for the number of patients we receive. We have proper equipment and plenty of sanitizing supplies.

The hospital has designated spaces for COVID-19 patients, and when an infected person arrives, we are able to provide the relevant medicine.

However, if someone arrives in poor condition, we stabilize the patient and then transfer him/her to the national hospital of El Salvador. The infrastructure is in place once more.

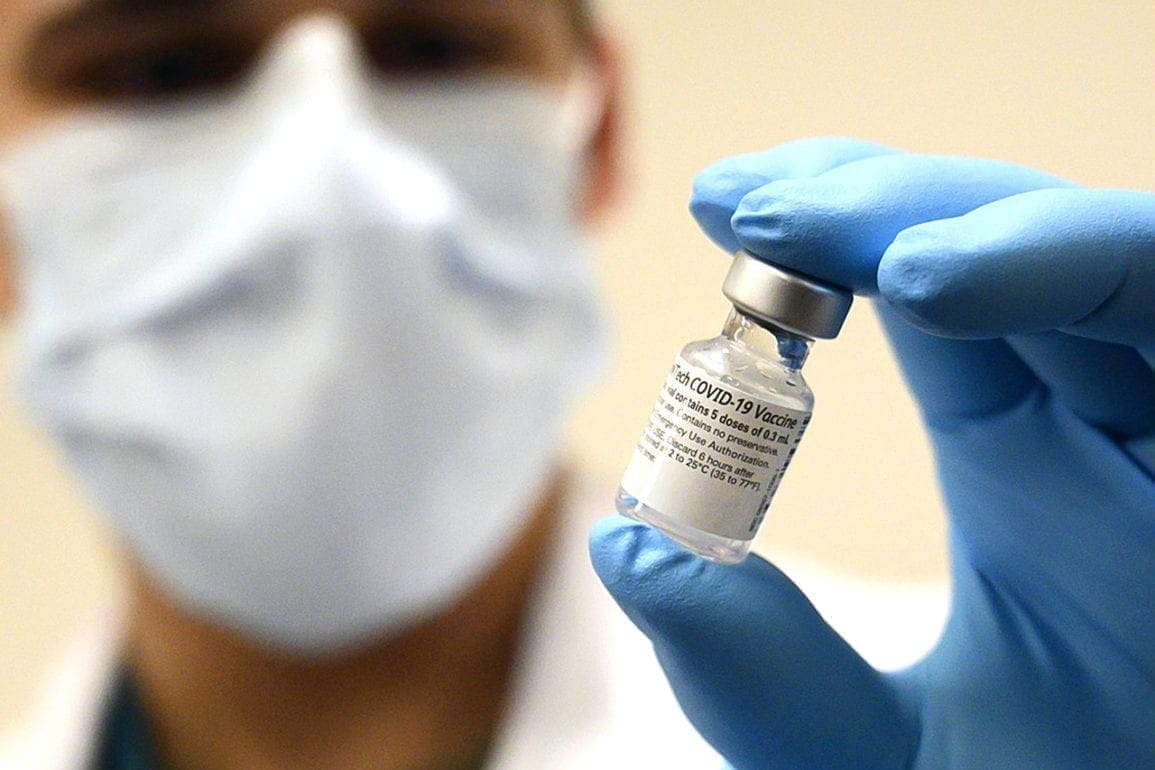

We are finally all vaccinated, which means the fear and anxiety that had plagued us is gone.

Finding hope and looking to the future

On one occasion, we saw in the news that in the United States, some nurses and doctors cut their hair to put on the biosafety suit more quickly; since the hair increases the risk of contamination.

Inspired, a hospital employee who had a hairstylist friend invited him in to cut women’s hair at our hospital for the same reason, to reduce contamination. Many lined up for a haircut with no hesitation; I found it so moving and one of the most beautiful experiences of the pandemic.

I have no doubt that many families still wonder whether they buried their relatives in those early days. Hospitals did painful things that won’t soon be forgotten, but I find comfort that it was due to ignorance, not malice. If another pandemic comes, things will be different, because we know better now.

The healthcare system does not have power over life, but it does have the power to fight for death to be with dignity. I feel happy because I tried to do my job and helped as much as I could.

We all come out psychologically touched. However, I am grateful to God that I am alive; for not having died in the pandemic. That was my main and greatest learning: God is faithful.