Bone marrow donation with rare mutation cures man’s cancer and his HIV

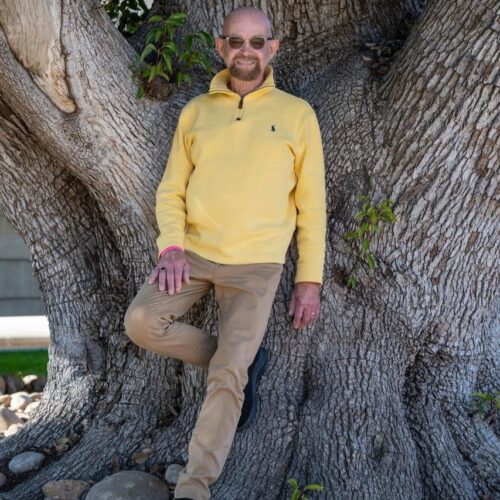

Sometimes, I still feel shocked to be alive. Every day, I acknowledge what I overcame. It makes me increasingly grateful for my daily life.

- 4 months ago

April 7, 2024

CALIFORNIA, United States ꟷ As only the fifth person in the world to achieve remission from HIV, every day I stop and think, “I don’t know how I can be so lucky.” I never imagined from my first HIV diagnosis in 1988 that, one day, I would be cured. I believed the HIV virus would remain with me until the end of my days. Today, I feel incredibly grateful for the life I lead, and I maintain a mission, to help those still in the healing process. I am proof that it is possible.

Read more cancer stories at Orato World Media, or dive into pieces featuring women and members of the LGBTQ+ community in our Sex & Gender category.

Contracting HIV: fighting for his life while battling the social stigma

In the early 1980s in San Francisco, HIV spread like a lethal cloud. We thought it primarily infected people from the LGBTQ+ community, like me. People spoke of a “pink plague” and I watched friends contract the virus and pass away. My heart broke. Feeling overwhelmed, I sought a change of scenery – to escape the death that seemed to haunt me. I went to live with a friend in L.A. for a few years.

When I began to feel sick, I distracted myself from it, fearful of testing positive for HIV. At that time, it felt tantamount to a death sentence. Then, my father died of cancer, and it changed my thinking. “If he had known earlier,” I thought, “he could have done something.” So, in 1988, I took the test, which revealed a low cell count and a positive result for HIV. Frankly, I did not feel surprised, and true to form, I faced the diagnosis with optimism. I never thought, “I’ll die in a year or two.” I focused on living each day.

At that time, the ignorance and social stigma around HIV and AIDS created fear. Many friends stayed away from me, worried about contagion. No one knew what to do. Year one proved the most difficult. The strong medications knocked me down completely. At times, I faced nonstop diarrhea, confined to my home. Yet, I remained determined to survive.

I put myself in the hands of science, volunteering to test new drugs as they emerged, unwilling to give up on myself. As I wove a new network of support, something amazing happened. In 1992, I met Arnie, my now husband. He also tested positive for HIV, and we became a great support for one another.

Man with HIV faces another devastating diagnosis: leukemia

Over the years, my life normalized as treatments became less aggressive and invasive. While I maintained my optimism, I believed the virus would always be with me. I never imagined being cured. When I learned about Timothy Ray Brown, the first person to be cured of HIV, I felt utterly shocked and filled with hope. I began to believe a cure was possible.

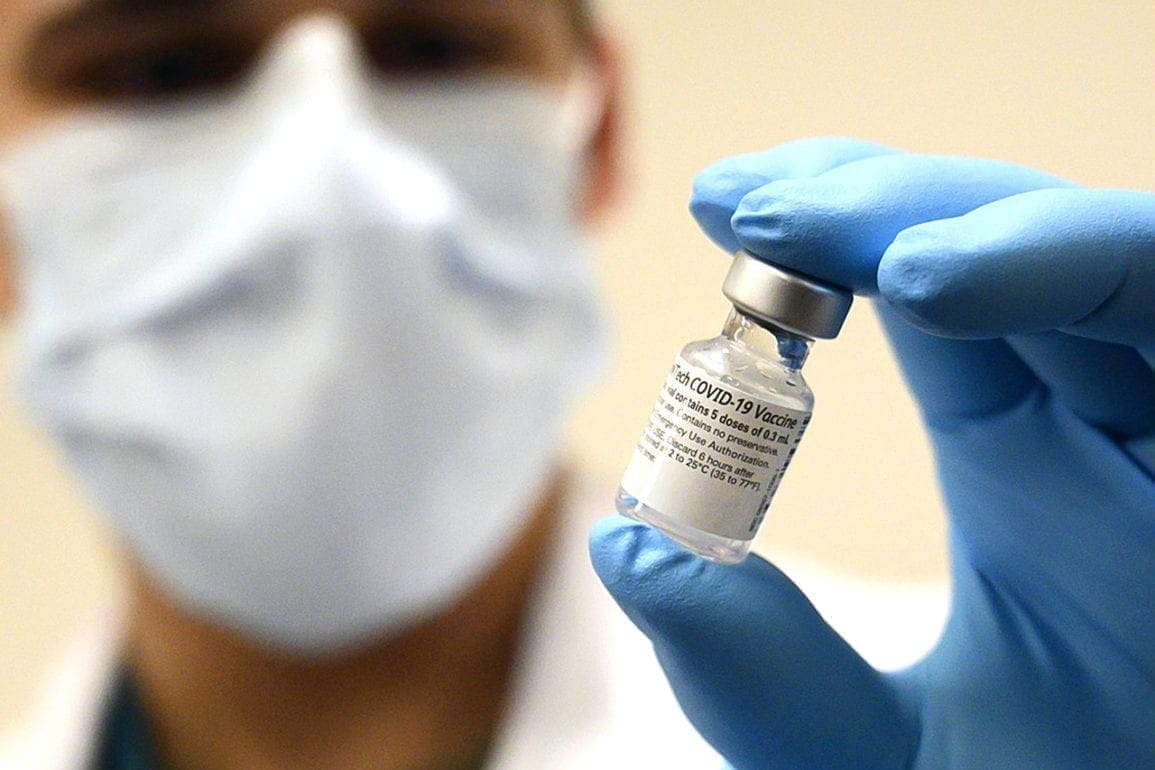

In 2018, 30 years after my HIV diagnosis, I attended my regular routine of doctor appointments and blood tests every three months. At one such appointment, I expected the normal results in my blood pathology, but something had happened inside of me. With the numbers off, doctors sent me to a hematologist and performed a painful bone marrow biopsy.

[Eight years after Timothy Ray Brown was cured of HIV], I was diagnosed with myelodysplastic syndrome, which later turned into acute myeloid leukemia. I maintained my usual optimism and began adding doctor appointments to the list. I did not fear death, but I also had little hope of a cure from cancer. Once again, I gave myself over to science and trusted the doctors to help me survive.

Though I believed my optimism to be foolproof, dark thoughts began to creep in my mind, like a sneak attack. I regretted my fate and questioned the reasons why I had to face yet another life-threatening illness. In moments like those, I shook the thoughts from my mind and focused on the next task. “Follow direction and let the professionals do their jobs,” I thought.

For five months, I received bone marrow transplants and chemotherapy sessions at the hospital. Nervousness and fear began to overtake me. I worried the treatments might fail and to control these feelings, I meditated, attempting to reach a state of serenity. The learning process this time felt long and arduous.

Going public and giving back: the movement for a cure

In 2021, about three years after my cancer diagnosis, the doctors delivered great news: my leukemia went into remission. After so long, I felt like I could breathe again. Despite my desire to always remain positive, I realized I had been holding onto anguish for far too many years. I simply contained the uncertainty.

Four times during treatment for leukemia, I endured bone marrow biopsies, and they always revealed the presence of cancer cells. The last time, my biopsy came back clean. Overcome with a sense of relief, it felt like the most beautiful day of my life. I wanted to move forward on all the things I set my mind to. Then, another piece of news arrived.

A short time later, the doctors informed me that not only had I beat cancer, but my HIV went into remission. I felt elated. From my diagnoses to living for years with HIV and cancer, the experiences shaped my personality. Empathy has become a major pillar in my life. I understand people’s suffering and maintain a desire to walk with them.

Millions of people live with HIV and I want to give them hope, to raise funds for HIV research, and to do the most important work of my life. After going into remission, I decided to come out publicly. My story circulated the media, at first labeling me as only “The City of Hope Patient.” As the months passed, I wanted to pin that medal on my chest and put my name to the story. Now I attend conferences, give speeches, and tell my story to help those fighting their own disease.

Sometimes, I still feel shocked to be alive. Every day, I acknowledge what I overcame. It makes me increasingly grateful for my daily life. Every now and then, I stand in astonishment, looking back on the days I got the news that I beat HIV and cancer. All I can think is, “Wow… how awesome!”