Kosovo War refugee feels adrift between two homes

I feel like I can’t reconcile the two halves of my heritage. I have a lot of Spanish in me, in my character, and in my way of acting. I also have a lot of Albanian. Those two parts of me are always in conflict.

- 4 years ago

March 29, 2022

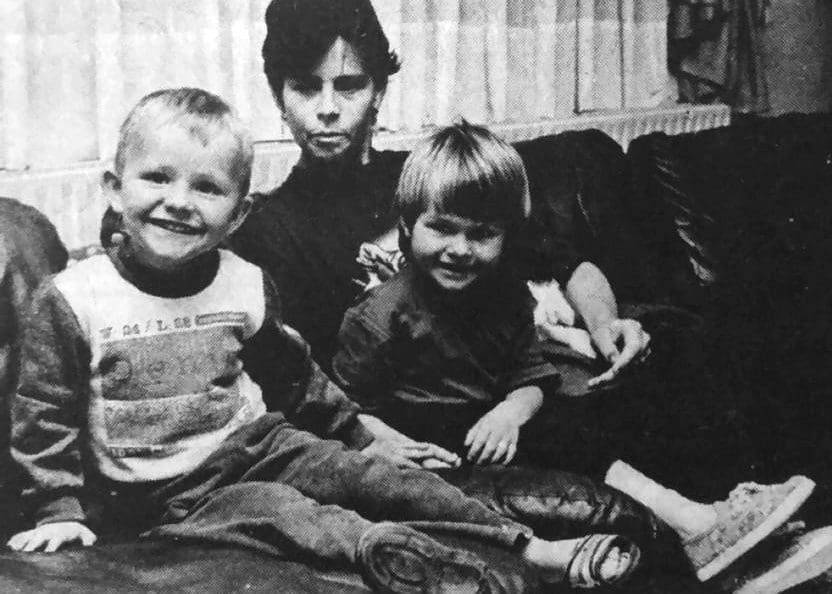

PDOJEVO, Kosovo: It all started in 1999, when I was 3 years old. I remember my mother carrying my brother and holding my hand. I have memories of my father’s sister with us, but not my dad.

The war in Kosovo started in 1998. Serbian troops were massacring entire Albanian families, so we had to leave Pdojevo, the town where we lived at the time. We fled to Macedonia, and from there, my aunt decided we would go to Spain.

Starting a new life in Spain

I have few memories of arriving at a refugee camp in Ávila without my father—in truth, a newspaper clipping reminds me that we were there. My father joined us there about a month later.

Marist brothers served the refugees there, who were all fleeing the war like us. One offered our family the opportunity to go with him to Madrid, to the Cardenal Cisneros University in Alcalá de Henares. We accepted, and my father got a job and accommodation at the university.

I remember that I had no problems adapting. I was very young, and it was easy to learn Spanish. I speak better Spanish than Albanian. I remember playing hide and seek under the university tables with my brothers when we were little kids, and the affection the administrative staff treated us with. My earliest memories begin there.

Other Albanian families left after the war; we were the only ones who decided to stay. We had to renew our residence permit every year and travel with the documentation stating that I am from an unknown country, since Spain doesn’t recognize Kosovo’s sovereignty. I remember the endless explanations at airport passport control.

I perfectly remember my 13 years in Spain, my entire childhood and adolescence. I was happy there, and I consider it my country. I never experienced any difficulty adjusting to my new home, or any racist comments towards me or my family, though I do remember how difficult it was for the teachers to pronounce my name when they took attendance.

However, in 2011, my father was fired from his job while we were on vacation in Kosovo. I remember thinking: now what?

Both Albanian and Spanish, yet neither at the same time

Johannes Anyuru wrote, “I wonder if I was destined to spend half my life in a place where they were unable to pronounce my last name and the other half in a place where I was unable to speak the people’s language.” That’s how I felt when I had to go back to Kosovo.

Although I was born here, I grew up in Spain, and when I had to go back I didn’t understand anything. I was forced to live in another world. There are very few people who can understand how I felt; how lost I was when I arrived.

My brothers and I spoke Albanian passively; we understood it, but we didn’t speak it or write it. I was already in high school when I learned to write the language that was supposed to be mine, by copying my deskmate. In that same institute, where my brothers and I were always “the Spanish.”

I feel like I can’t reconcile the two halves of my heritage. I have a lot of Spanish in me, in my character, and in my way of acting; I also have a lot of Albanian. Those two parts of me are always in conflict.

Exiled from a beloved home

I know that I am not the only one who has gone through this: returning to a country I once fled, though I no longer consider it mine. However, the rest of the “returnees” can at least come back to that refuge to visit; they can see their childhood friends or even look for work or study in the country they called home for so long.

But not me. Neither my brothers nor I can. Nor any of the refugees who were in that camp in Ávila. Spain insists that I belong to an “unknown country” and bars me from entry.

What was our home for 13 years has made it clear to my family that we are no longer welcome.