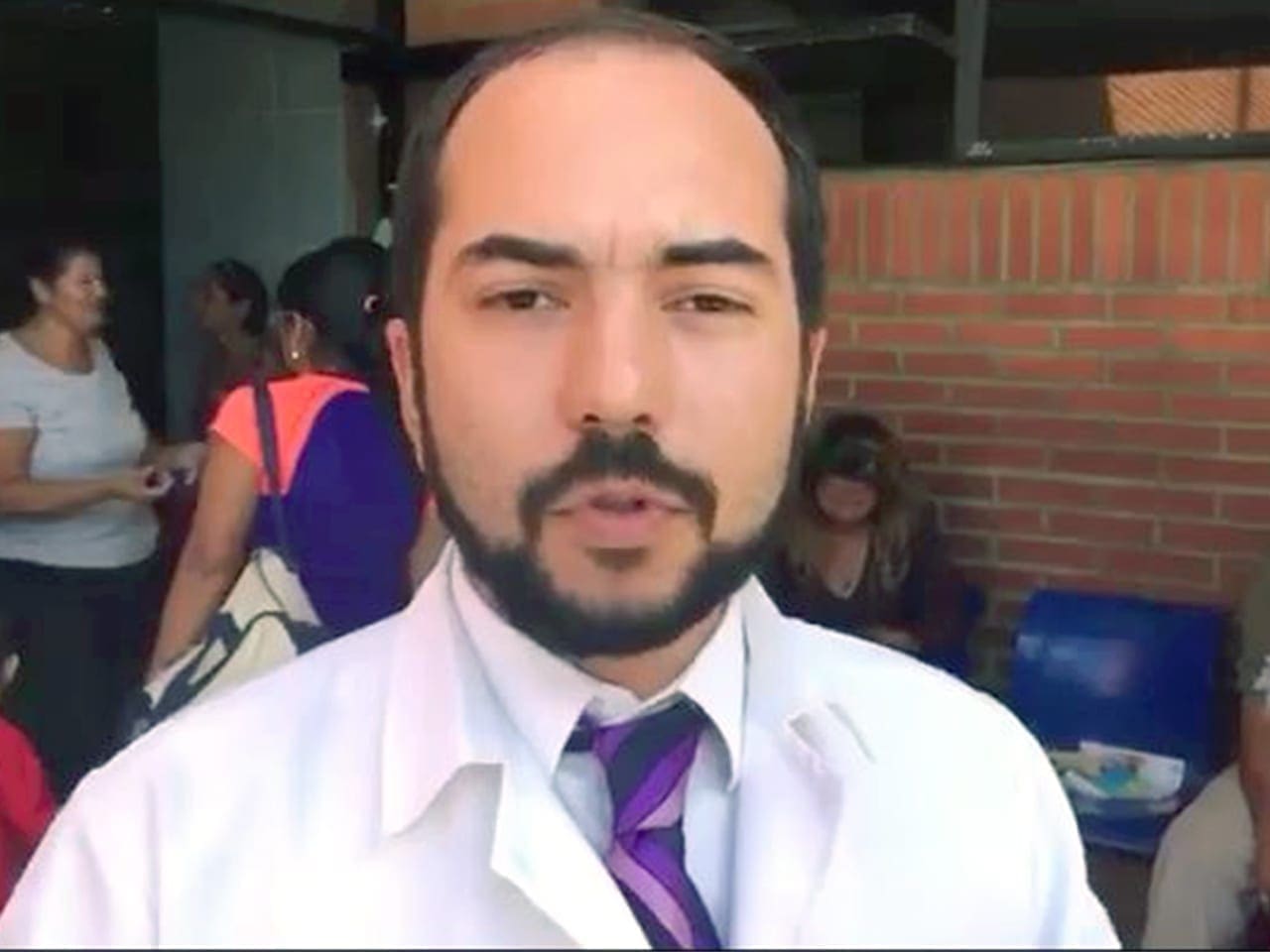

Fighting COVID-19 with few resources

Doctors in Venezuela must fight through horrible conditions and the grief of losing colleagues to Covid-19 while treating patients.

- 5 years ago

October 23, 2020

BARCELONA, Venezuela — Many people are surprised when I tell them that I still practice medicine at the Anzoátegui State Hospital. When they ask me the reason, I can only say that I don’t have any other option other than to resist.

I live in a country collapsed by hyperinflation, crime, poor public services, malnutrition, diseases already eradicated in other parts of the world, and extremely low wages. As if that weren’t enough, at the health center where I work, I suffer from a lack of food, medicines, and medical supplies.

Ten per cent of the residents left the hospital because they could not bear the working conditions, the Covid-19 pandemic, not to mention the salary of just $2 USD a month. Going to work represents an almost impossible task for me due to the lack of public transport and fuel supply.

A hospital without water

If I had to identify the most serious deficiency that I suffer at Dr. Luis Razetti, I would say it is the scarcity of water. How does a hospital work without water? It is true that the tanks in the health center can store more than a million liters, but the service is irregular and poor.

The hospital is a complex made up of three buildings, one with nine floors and two with six, and in all of them, there are dozens of damaged pipes and bathrooms, which is why a good part of the water is wasted.

And I mentioned water as the most serious problem, but it is not the only problem in a hospital that has already more than 40 years old.

Several bathrooms are unusable, the smell of stagnant water is unbearable. Some areas are dark due to the lack of adequate lighting and pushing a stretcher around these places is a challenge. Also, many air conditioners do not work — in a region where the daily temperature exceeds 30 C — and of five elevators only two work intermittently and do not reach all floors.

Even so, after a lot of pressure and without stopping working, the government installed an exclusive water tank for doctors like me, who are dedicated to treating patients with Covid-19. Before that, I was unable to wash my hands, use the toilets, or shower after attending people with coronavirus. Of course, to wash up I must bring my own soap because the official budget does not cover that expense.

Hanging on for the people

The hospital has some supplies and medicines thanks to the people who live in the area around the place. The medical center is located between the cities of Barcelona, Puerto La Cruz, and Lecherías. People and civic organizations donate gloves, masks, medicines, and other equipment. We survive thanks to charity.

There are women who daily bring nutritious meals. Without them, it would be impossible for me to get through a full day’s work with only two sardines, a little rice, a portion of instant mashed potatoes, and two fried arepas.

No doctors

The second great deficiency is the lack of personnel. In 2011 the health center had 6,500 workers, today there are only 2,700 left. Although I am a traumatologist, I must take care of hypertensive people or diabetic crises.

However, this is little compared to what the rest of the Razetti staff do. Theoretically, there should be around 50 people in the cleaning department for every eight-hour shift. However, sometimes there is only one heroic person dealing with hospital waste, for the entire complex of three buildings.

This amount of waste normally consists of pads, needles, and scalpels, dressings, sanitary napkins, bandages, gloves, probes, all of them used and contaminated. The odors emanating from these biological waste create an unbearable environment to work. On the other hand, the morgue cellars are damaged and the smell of decomposing corpses is disgusting.

Sent last goodbye

For me, one of the most difficult moments is assimilating the death of my colleagues who, like me, are also trying to resist in the midst of a global pandemic accompanied by an economic and social crisis that is hitting the country.

I recently sent my last goodbye to a friend, Dr. Gracialis Rangel from the Emergency and Disaster Service, who battled for days in intensive care with symptoms associated with Covid-19. Like me, Gracialis had aspirations, dreams, goals, objectives. I wonder “What for?” It is impossible not to put yourself in her shoes and not feel that blow so hard and so close.

The worst thing is that the death of Gracialis was the first of many. I have no chance of recovering from one strike when another immediately happens.

One of the advantages of forming a network with the family and friends of sick colleagues is that we all collaborate to get the treatment they need.

For example, a 100 mg vial of Enoxaparin, costs $ 5 each. Each patient needs a blister twice a day, which is an entire salary from that sick doctor, spent in the morning, and another salary at night. Together we participate in campaigns to search for medicines and we accompany family members until the recovery or death of the colleague.

It is hard for me in this country context to get up and talk about everything that I go through in the midst of this hospital and health crisis. I really feel bad about what is going on here. We suffer persecution from the government when we raise our voices and that persecution can finish in dead.

I like to think that people don’t die when they leave this world, they die when we forget them and it is particularly unfair that I forget my colleagues who have given their lives for others. I can not permit myself to stop remembering them.

Tears become a self-defense weapon to keep on working for the others. In the midst of these painful circumstances, I had the opportunity to connect with families of sick and deceased colleagues, which allowed me to create a network of financial, but also moral and spiritual support.

Despite the pain and suffering that I go through every day, I prefer to focus on resisting and participating in campaigns that are being carried out in order to get some supplies and medicines.

The only way to be grateful is to strive to do my best job and continue to resist.