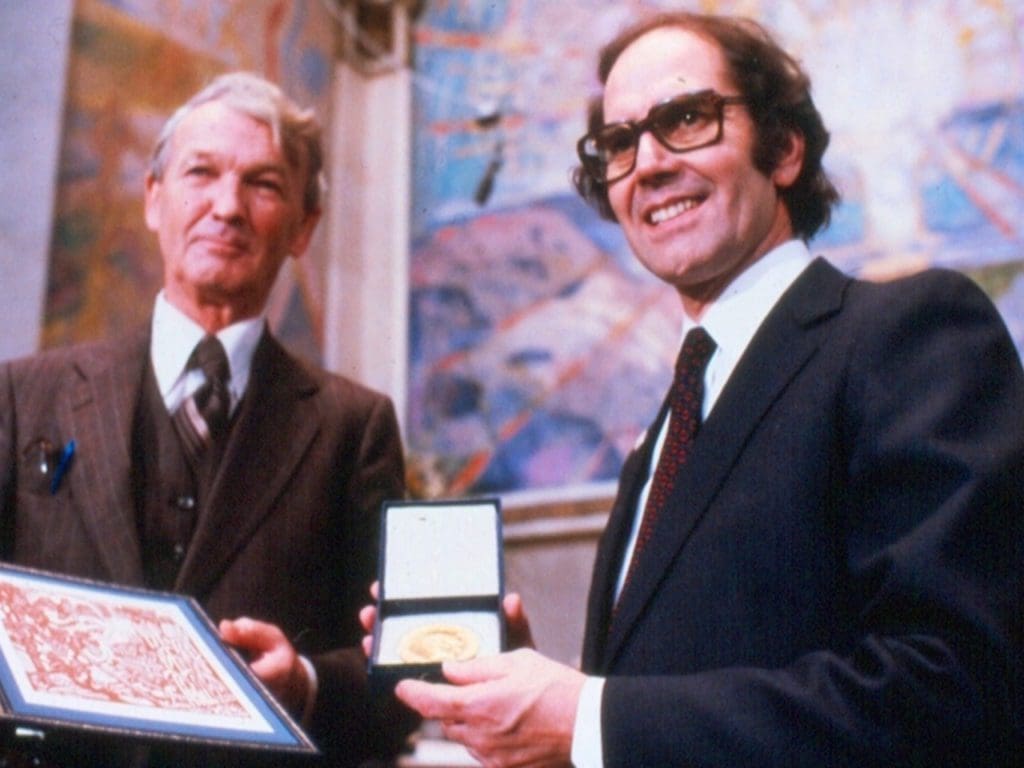

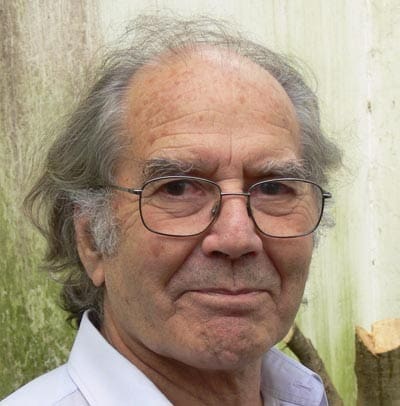

Nobel Peace Prize winner survived torture by Argentinian police

In his Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speach, Aldolfo Perez Esquivel said “The lights and shadows of life must be shared”.

- 4 years ago

September 14, 2021

BUENOS AIRES, Argentina – On April 4, 1977, I renewed my passport at the Central Department of the Argentine Federal Police.

I was working with the Peace and Justice Service, a Latin American movement that advocates for peace and human rights through active nonviolence. We were fighting the oppression of the Latin American people by military dictatorships.

At the Department of Police, without a judicial process, I was arrested. I never imagined this would become the worst moment of my life. I was detained and tortured for 14 months.

Anguish consumed him

Torture is an archaic practice. It destroys you physically and attacks you emotionally and psychologically. The profound desolation and humiliation are worse than the physical pain.

[As a political prisoner], my captors often sought to humiliate me; to break me mentally and physically. In the worst moments, I felt infinite anguish. I was paralyzed, drowning in confusion. Guilt often followed for getting to that point.

I took refuge in a single photo I had of my family. My heart broke as I longed for them. I wondered all the time how they were doing.

While I was in “the tube,” a very small, dirty, smelly cell, an officer told me, “God will not save you.”

Prisoners murdered on the “flight of death”

When I mention the “flight of death,” my skin prickles, and my eyes fill with tears. On these trips, the military threw people out of airplanes. Despite all the torture I endured, I never thought I would witness such a heinous, dehumanizing, and heartless situation.

During the ascent, they did not say where I was going. I realized the aircraft was flying in circles because I recognized the cities of La Plata, Montevideo, and Colonia.

Without hesitation, I dared ask what would happen to me. They gave no answer. I tried to keep myself psychologically whole, but death stood close. Despite my anxiety and sense of helplessness, I worked hard to maintain my sanity and connect with my ideals.

After two hours of circling, the plane landed at the El Palomar Airbase. The weather was getting colder and [the atmosphere] more tense.

I breathed a sigh of relief [to have survived the flight], yet I was exhausted and disgusted, being witness to so many crimes.

Captive escapes Argentinian government awarded the Nobel Peace Prize

Two days before the 1978 World Cup, hosted by Argentina, my captors unknowingly set me free.

[That day], I left unit nine, and the agent escorting me stopped to load gasoline. He took off my handcuffs, left a gun on the seat, and got out of the vehicle. My mind was filled with questions.

Although I wanted to take the gun and flee, I knew many prisoners got killed in alleged escape attempts. I decided to expose my hands and, when the officer returned, I told him I hadn’t noticed the weapon.

We continued on our way and I felt uncertain. Several miles later, in the middle of a field, a green Ford Falcon stopped. The officer told me to get out. Almost without breathing, I fled – my gaze lost and semi-paralyzed.

I cannot remember what happened in the following hours. My next memory is coming home and hugging my wife. I was detained for 14 months and kept on surveillance for another 14 months after that.

I found out international organizations had pressured the government to release me. The government didn’t want to comply. While imprisoned, the guards would tell me, “You will leave here with your feet forward,” [an Argentinian expression meaning you will leave dead or in a coffin].

Several years after my captivity, I was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. After having survived so many transgressions, my reward arrived. I received it with great pride and joy.

I trust my people to remember what happened, who did it, and what their motives were. Knowing history directs us toward progress. It ensures we do not allow these events to happen again.