Former interpreter for US, Canada left behind in Afghanistan

I closed the shop and rushed to my house. The bodies of my children and wife lay buried under the debris. My father, brother, and neighbors helped me carry my dead family out of the rubble.

- 3 years ago

October 5, 2021

ANDAHAR, Afghanistan ꟷ A wooden box—secured by rope and thrust in the trunk of the convoy’s armored vehicle—contained the body of my fellow interpreter. The smell of his decaying flesh emanated out of the unburied coffin.

Three days earlier, an improvised explosive device had detonated beside our convoy on the way from Kandahar to the Nawa District.

The other interpreters and I were accompanying a supply team of American, Australian, and Canadian soldiers to train the Afghan National Army on radio maintenance.

The explosion killed my platoon sergeant and the interpreter and injured two other soldiers. An airlift transported the military personnel back to base, while the dead interpreter remained with the convoy.

Eventually, the Afghan National Police picked up his corpse and returned it to his relatives.

Years of Service an Afghan interpreter ends abruptly

I became an interpreter in Afghanistan to support my parents, wife, and children. For four years, I served the U.S. 82nd Airborne Division and 4th Infantry Regiment in the Ghazni Province.

I worked hard to increase my technical skills and in 2011, joined the Coalition Advisory Team in Kandahar, where I lived most of my life. Then I was assigned to the 205th Hero Corps, a radio maintenance facility.

In early March 2012, my father fell seriously ill. I left my post with a convoy mission to the Urozgan Province to be by my father’s side.

My father survived his illness, but the short trip to the hospital turned into a three-day ordeal. When I called my commanding officer to explain, he fired me.

Having been relieved of my work with the U.S. military [after five years of service], I opened a shop in Kandahar City. We believed the Western-backed government in Afghanistan was there to stay.

Taliban takeover leaves former ally in fear for his life

On Aug. 13, 2021, a plane soared over the city as explosions rocked downtown. I stepped out from behind the counter of my shop to see commotion erupting in the streets.

My neighbor ran up to me and said a Taliban incursion was sweeping the country. My home had been struck by mortar fire.

I closed the shop and rushed to my house, where the bodies of my dead children and wife lay buried under the debris. My father, brother, and neighbors helped me carry my dead family out of the rubble and perform an Islamic ceremony.

We washed the bodies, covered them in a cloth, and prayed together. I could not sleep for three days. My brother took me to a doctor who prescribed medication, which helped restore me to sanity.

Like everyone trying to get out of Afghanistan, I went to Kabul in search of the Canadian and U.S. embassies. They were already closed, so I applied online for refugee status in Canada and headed to the airport.

Crowds of what looked like a million people like me swarmed the front of the airport as the Taliban soldiers fired warning shots in the air. I saw the Taliban rip up people’s documents as the guards held off the crowds.

An explosion rocked the airport and sent us all fleeing for our lives. I returned to Kandahar to be with my parents and sibilings.

Rumors swirled about of the Taliban killing former employees of western governments. Since then, I’ve been in hiding in my parents’ house.

I applied for refugee resettlement in Canada over a month ago with no reply. Our only hope now is the world won’t forget my family’s sacrifices.

I know the danger of telling my story, yet I believe it my only way out.

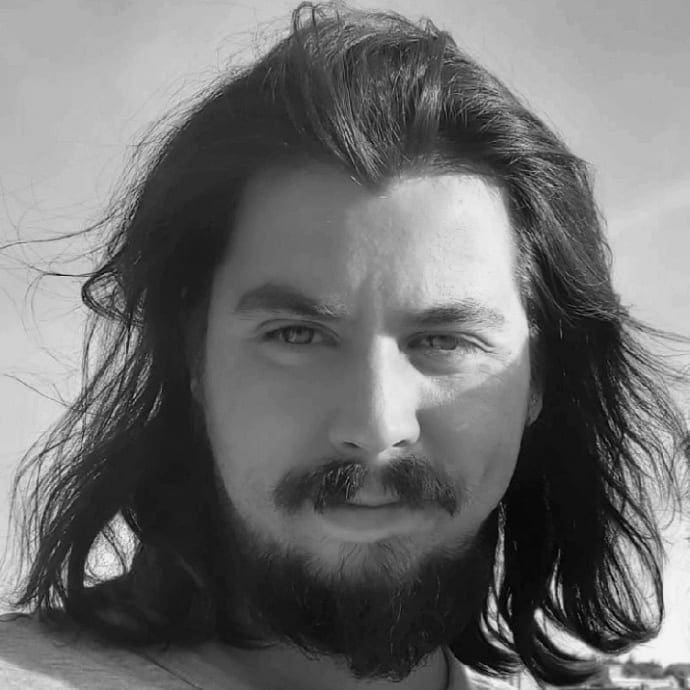

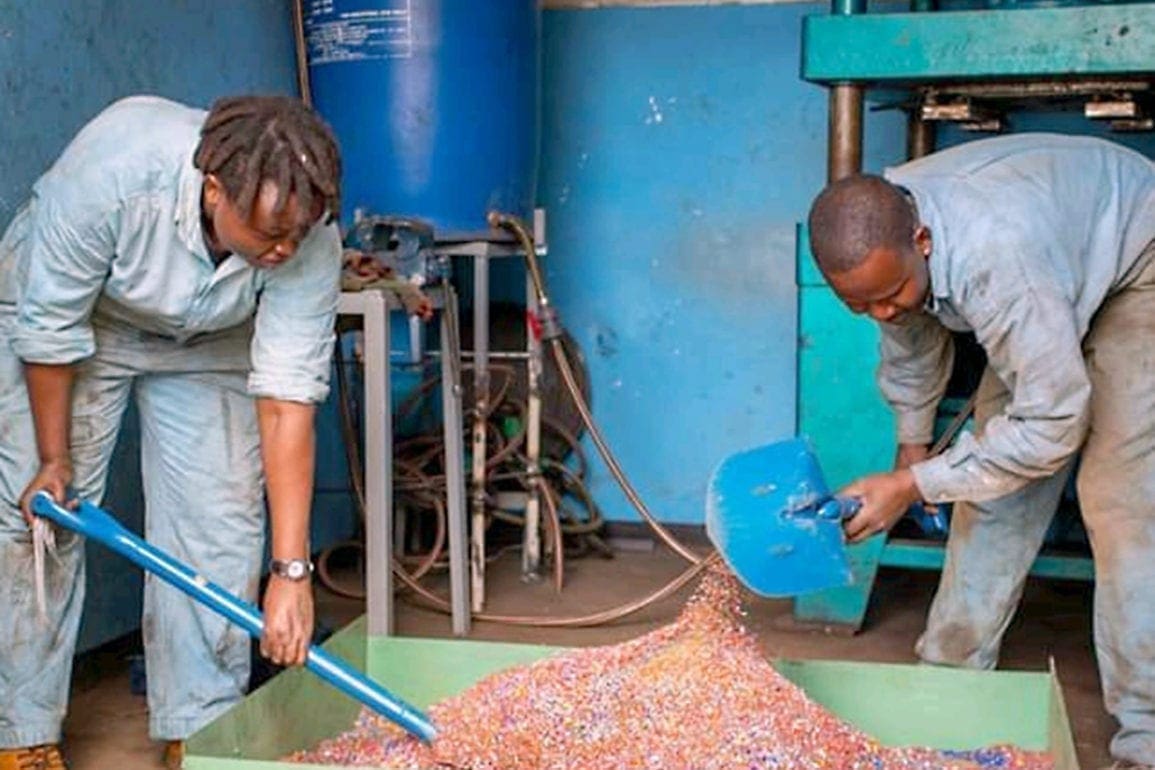

He now fears for his life in Kandahar | Photo courtesy of Abdul Ghafoor Khpalwak