Potato farming, past and present: Colombian farmer tries to survive despite increasing obstacles

The hardest thing about living in the countryside is the dedication required in terms of time and money. It is hard to go into debt in order to be able to buy all the supplies a crop requires, but many small farmers like me have no other alternative.

- 2 years ago

May 18, 2022

LA CALERA, Colombia—I’ve been growing and harvesting potatoes since I was a young boy. It’s hard and dirty work, but it is how my family survived. I’ve returned to the fields in an attempt to help support my family, but things are no easier.

Potato farming is in my blood

My father came to La Calera, a town near Bogotá, when he was 32 and immediately began to grow potatoes. At that time, all the land belonged to a single hacienda (plantation or estate) called “El Encenillar.” It had four owners, but over the years they began to divide the land out and sell those plots. My dad and the rest of the growers in this part leased those lands to be able to grow crops.

Thanks to hard work, around 1958 or 1959, my father bought 6 fanegadas (equivalent to about 9.5 acres). He told me that this land had cost him 20,000 Colombian pesos (about $5 USD), which he paid little by little. He eventually had to sell half a fanegada to finish paying.

My family consists of 11 siblings: nine men and two women. The older children helped my father in the fields, and my mother used to cook for the farmworkers on a wood stove. As a result, today she suffers from health issues with her lungs.

My father stopped growing potatoes because of his age; it is hard, back-breaking work. None of my brothers continues with farming, only me—however, I cannot dedicate myself exclusively to that either.

Working the fields as a child

When I was a child helping in my father’s fields, we could only take the load out in a yoke of oxen or on the back of beasts; it was a journey of half an hour there and half an hour back. There was no way to get the load out by truck since the only roads were bridle paths the mules themselves forged. Now, those same paths are unpaved roads.

I was 8 when I started helping my dad. Since I was still little, they put me to pick the “riche,” which is the last potato left from the crop. First, the thick potato is collected, then the medium/second highest quality, and then the riche, which is the smallest, and used to feed the pigs. When I was older, I had to herd the mules that carried the loads of potatoes.

I also had to carry out my mother’s home-cooked food to the workers by foot. Loaded with heavy pots of food, I walked those same bridle paths as the mules four or five times a day.

Cultivating the potato could take three weeks to a month, depending on the amount planted. Similarly, the harvesting process depended on the fanegadas or the amount planted. A mule could carry 250 pounds of potatoes in a load, and we typically harvested up to 30 loads.

The growers themselves had to sell their cargo of potatoes directly at Corabastos, the largest wholesale market and central supply center in Bogotá. To sell there, we had to arrive at 3 a.m., which meant leaving the farm with our loads at 1:30 a.m.

The traders were—and are—the ones making the money. They buy from the farmers without any negotiation.

Facing obstacles of plague, poison, and lost crops

As for me, I’ve seen ups and downs while farming for myself. I managed to plant up to 20 loads some years, but because of the cost of maintaining the crop and the dedication it requires, that was the most I could handle. I lost a lot of money, and it went very badly.

In 1994 I had done well with crops that I planted on rented land. So the following year, I rented more and planted six loads of potatoes. Little did I know that would be the year everything changed for the worse thanks to the arrival of the Guatemalan moth.

A plague that abounds in summer, these moths decimate the potato crops, leaving the plants completely black and inedible in 15 days. My crops in 1995 were a total loss.

To prevent the pest from damaging the crop, we have to spray pesticides several times while the plants grow. Back when my father farmed, the potato did not require as many chemicals as it does now. We diluted a chemical in water and used a yoke of oxen to disperse it.

Nowadays, the fungicides are much stronger—it feels like all we eat are chemicals. But if we do not spray them, the harvest will not prosper, and nothing will grow.

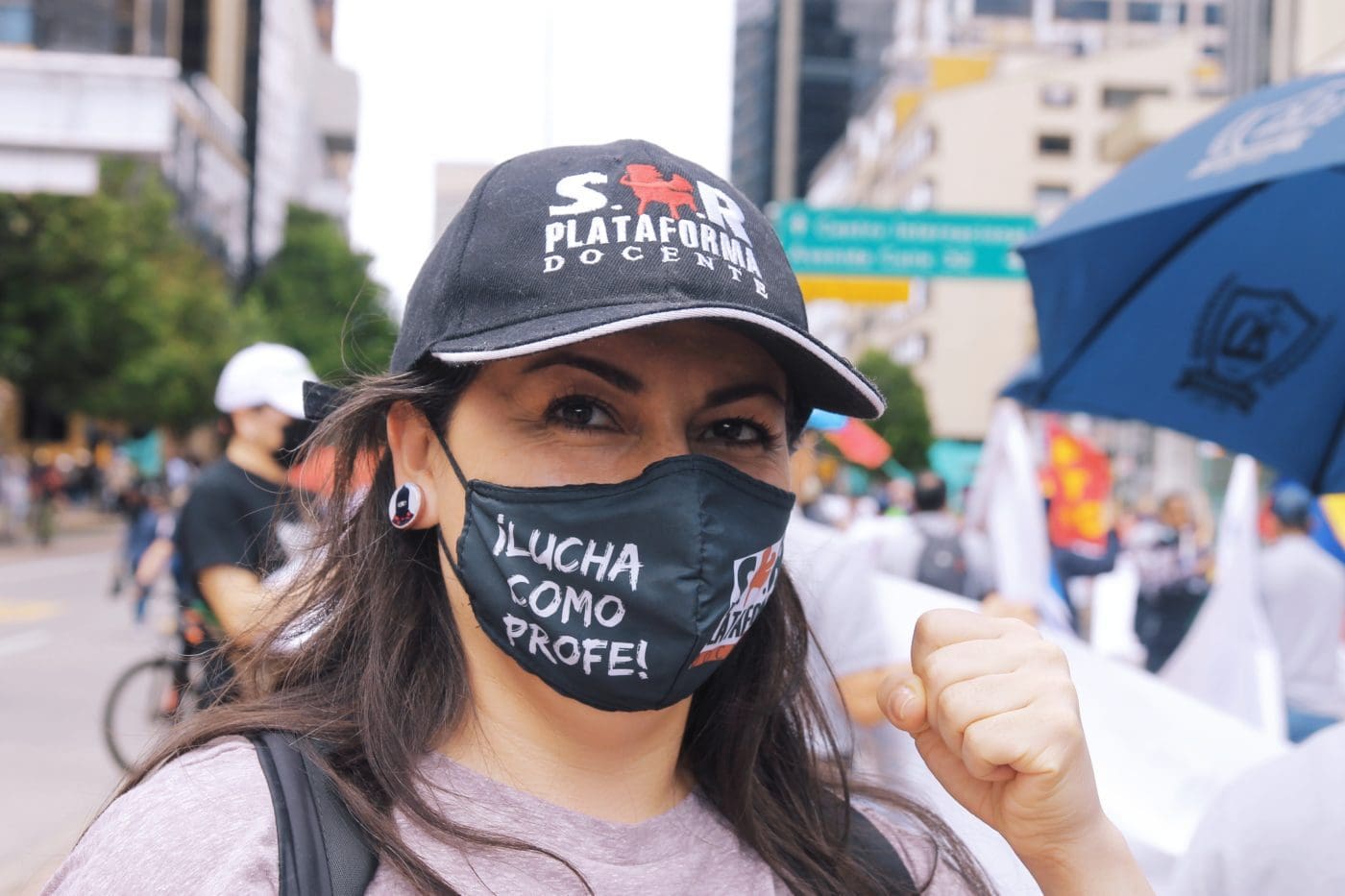

Continuing the fight to farm and make a living

The last big crop I did was in 1998, and I worked another job for stability. After many years of not growing, this year I did it again, but on a small scale. I have a piece of land behind my house, and there was enough space to plant two loads. I also cut grass for a golf club.

The hardest thing about living in the countryside is the dedication required in terms of time and money. It is hard to go into debt in order to be able to buy all the supplies a crop requires, but many small farmers like me have no other alternative.

The farmers who are part of an association receive some support from the government such as tractors, fertilizers, or seeds, but it’s minimal compared to all the expenses. Those of us who are not must take out of our pocket to pay for everything.

In addition, the earth itself has changed. There is less land to farm because the country has become built up; there is more cement than crops. Climate change plays a role too—there used to be several nacederos o nacimientos, (water springs), but now they are scarce. When it is very hot, the rainwater that has fallen is lost. In the past, the water did not dry up.

Despite the factors weighing against me, I hope that this year things work out and I can earn some money.

All photos by Mariana Delgado Barón