Seeing the forest for the (illegal) trees

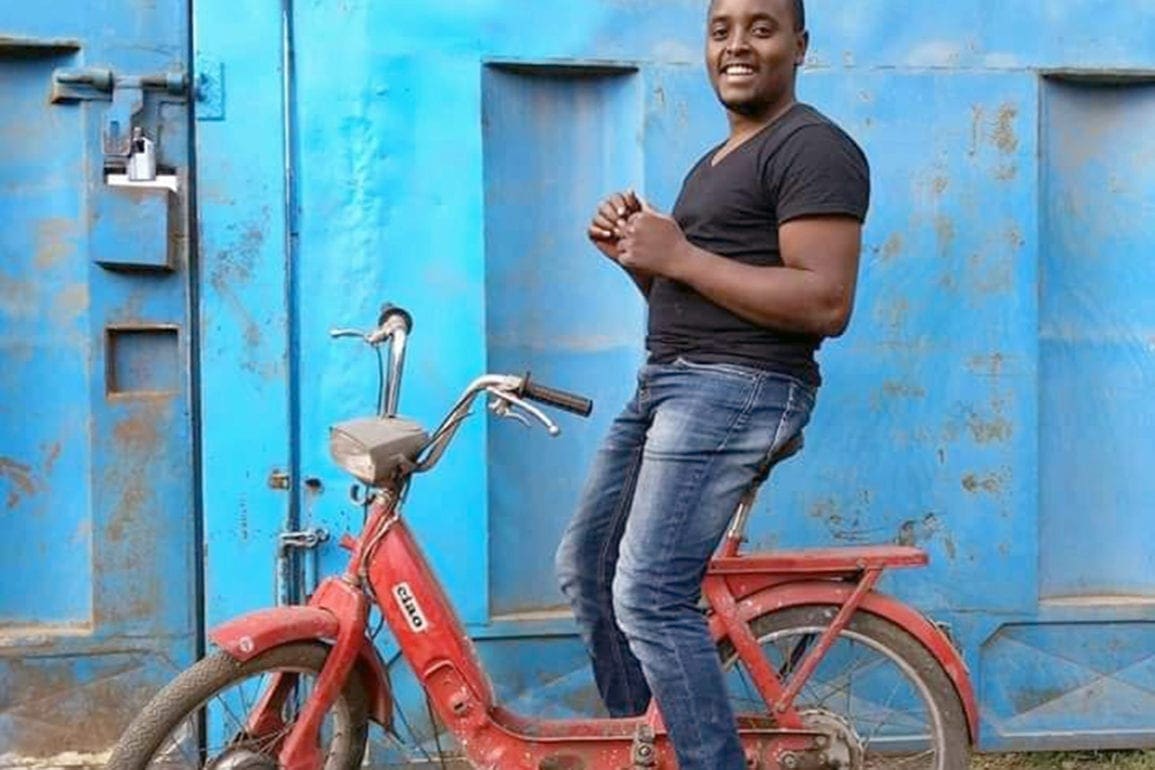

I started illegal logging several years ago, and I have managed to survive. It is risky because I have to be swift and slippery to avoid the law.

- 5 years ago

May 19, 2021

LOLGORIAN, Kenya — In Kenya, illegal logging can result in a severe penalty, but I do it to put food on the table and educate my children.

I started illegal logging and charcoal burning several years ago when I lost my job, and I have managed to survive.

I thank God that as of now, I am able to make a living. It is risky because I have to be swift and slippery to avoid the law.

I was introduced to this business by a friend when I could not farm because of the scarcity of land in my village.

Quick mentorship

Before I started my own business in the forests, I worked for my friend to learn the things I needed to know. He wanted me to understand how to work with the authorities and avoid them when required.

Logging in these forests calls for networks that can let you off the hook if caught by the police or forest service officers. I learned and perfected this art.

I can now set up as many furnaces as I need in this forest and hide them, even with smoke emanating from the fires.

Illegal activities in the forest

Other loggers are burning charcoal like me and some are cutting down trees solely for timber and fencing posts.

Each one of us has to pay a bribe to continue our activities. Those of us who deal with charcoal pay an amount set by the officers manning the forest.

In this forest, you have to follow the rules of the jungle because the penalties are severe.

We come in with power saws, axes, and blades to cut down trees that are under protection. Sometimes it is hard to believe that the authorities hear power saws grinding in the forest, but turn a deaf ear.

‘Legal’ illegal behavior

This occurs because we paid for our existence in the woods, and our illegal activities are ‘legalized’ by these payments.

I work with police that should be protecting the forest, but become like business people. They are the ones selling trees to loggers like me and many others.

Some police bring in their own workers, and they are the ones cutting down trees and selling timber and posts. You will not see them selling the timbers in timber yards or transporting them.

As for people like me, our only option is to keep logging.

This work has no time for rest. I only rest when my furnace is burning, but I still have to be vigilant to safeguard it from bursting into flames.

No rest for the wicked

I also have to be keen because customers come into the forest at night. I need to hear them when they are approaching in case the cellphones do not work. That means there is little or no sleep in this business.

I am lucky that my customers come with hundreds of donkeys or motorbikes, so I can hear them when they are approaching.

At night, there are officers handling roadblocks along the road. These officers also get their bribe to allow charcoal sellers to proceed to their destination.

Charcoal sellers, who are my customers, have to pay a hundred shillings for every donkey. In fact, you have to pay for each donkey carrying charcoal at every roadblock.

Bribes factor into pricing

These bribes affect the price per sack of charcoal because you must factor in all of the payments.

The whole system works like any other market where taxes are cascaded downwards.

A large percentage of indigenous trees are hardwoods. This type of wood is in high demand and almost every carpenter wants them.

Indigenous trees produce good quality products compared to other breeds like eucalyptus and cyprus.

High demand means that a logger in the forest can make a killing from their market monopoly.

Indigenous tree sellers are also connected to Kenya’s forest service police. These police officers control the number of businesspeople in the industry because they also sponsor them. They patrol the forest and set the prices for illegal timber and charcoal.

High demand

While I am not saying the government knows we are cutting down trees, it is common knowledge that people here use charcoal or firewood in their kitchens.

No one uses a different source of fuel apart from these two. There is no electricity and no one can afford alternative methods like gas and generators.

Everyone is trying to minimize cost and that means they have to come and buy charcoal. That is how I get to earn a living.

We even sell our charcoal across the border to Tanzania. Charcoal from indigenous trees is top quality. That propels its demand above charcoal from other trees.

How I buy immunity

To continue logging in these forests, I have to pay for my stay, so I do. These police officers that guard the forest will not listen to you if you do not have money to bribe them. In my case, I pay them to access the forest where the trees are big enough to meet my financial targets.

An eighth of an acre goes for four thousand shillings, but they can extend that when the area has fewer mature trees. I am at a level now where I bribe based on the number of furnaces that I erect.

I pay one thousand shillings per furnace, and I find it cheaper because I erect oversized furnaces intending to produce as many sacks of charcoal as possible.

For sustainability in this business, I have to lower the cost of a bag of charcoal to allow my customers to get some profit after bribing cops along the roadblocks.

Symbiotic relationships

That sense of symbiosis is the reason I sell a bag of charcoal for as low as three hundred shillings.

By the time my customer gets to the final user, the cost of that same bag escalates to over 1,500 because the last buyer has to carry all the bribes paid along the way.

Sometimes I ask the police to escort my customers out of the forest because they came for goods at night. It is risky to walk for such long distances after dark because of the insecurity in the whole region.

In some instances, one has to dodge wild animals like hyenas that attack donkeys. With a small payment, police can escort you safely to the other end of the forest.

Sometimes I take advantage of the police accompanying their own products out of the woods, and have my customers tag along.

This way you get security and, at the same time, police at roadblocks will not give you a hard time. It is a kingdom that operates like a fiction movie, but it is real life.

What happens when I fail to bribe?

Being in good standing with forest guards is what I must do to continue this work. A slight mix-up can be disastrous to my business.

I have learned to survive in this jungle with its strict rules.

Here, punishments bring you down economically or even kick you out of business. One time I failed to pay my bribe and the police on patrol pricked my furnace, let air in, and poured petrol into it.

The whole furnace burst into flames, and I could not get one bag of charcoal out. As I said, it is a jungle with its rules, and I have to abide by them to survive. I pay the bribes as early as possible to avoid unnecessary losses.

Being an illegal enterprise, nobody cares about the pain you have to endure when you incur losses. Everyone here is rough and somewhat inhuman.

RELATED: App helps Kenyans report illegal logging

Getting kicked out

I have seen police kick people out of business because of slight misunderstandings. Failing to raise a bribe due to some financial stretch led to several loggers getting kicked out.

That is what I fear the most because I do not have anywhere else to run to if they kick me out. It is not easy to come back when they kick you out since they are the same people to let you in.

The same police officers that you have been working with can arrest you and send you to court for cutting down trees.

Every time I imagine being in court as a respondent against the government, I pay the bribe and enjoy peace in the rough jungle.

This job has separated me from my family. I only see them briefly each month then rush back to the forest to keep working.

I do not regret doing this work

I do this job to meet my family’s needs. This life is better than being a thug out there. I do not hurt anyone with this job, I only break the law, but I am not alone in this.

Remember, even those that are mandated to protect the forests are here logging, too.

The economy of this country is also a hurdle I cannot just leap over in the name of doing what is right.

Life is hard out here, and as long as I have not killed anyone or stolen from anyone to earn a living, I think illegal logging is better than other crimes.

Doing the crime

I understand that what I do amounts to environmental crime. It is a criminal offense in the sense that we have evicted several wild animals that use these forests as their home.

This work means I am hiding from the Kenya forest service members and the Kenya wildlife service. I hope that I will find another job to avoid having to live in a hideout like a wild dog.

If I ever get caught by the strict police officers, those I work with in the forest will step aside as I get arrested.

Rules are straightforward. You must carry your cross. If you are caught they can lay unimaginable pain on you. You die alone.