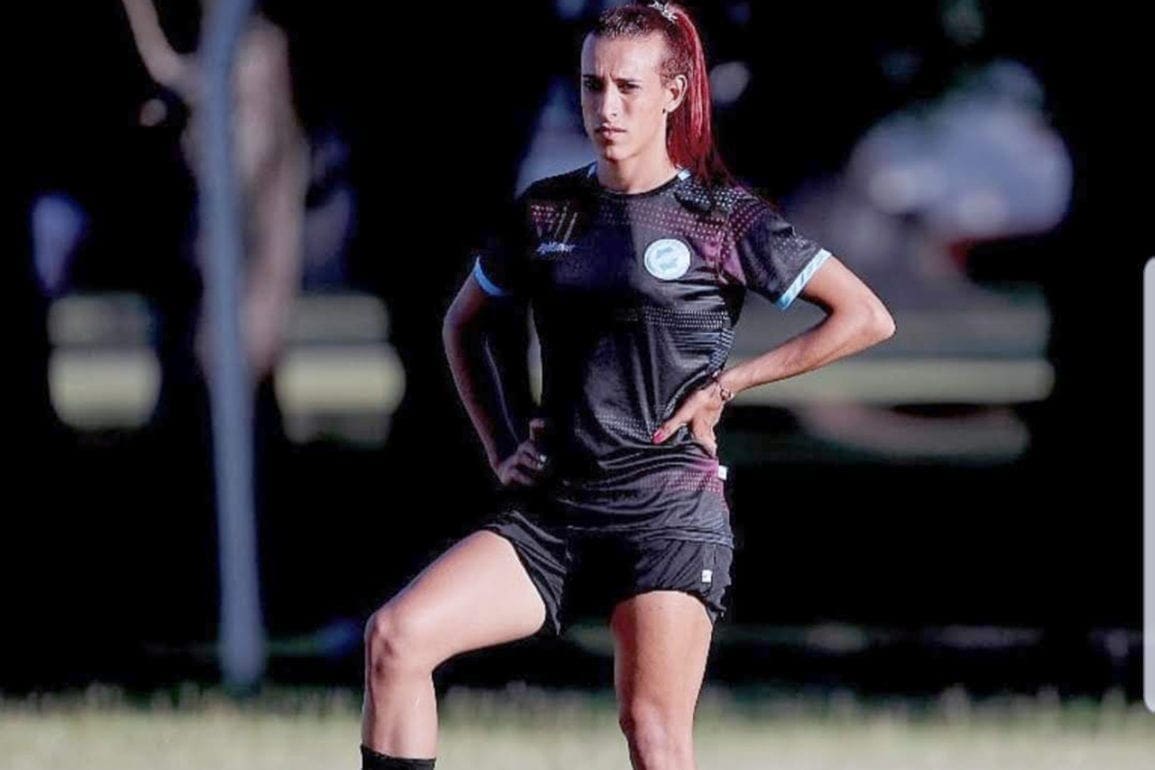

Transgender nurse smashes glass ceiling

Despite meeting all the requirements, my superiors tried to stop my candidacy. The discrimination I seemed to escape returned once more to halt my dreams.

- 5 years ago

June 17, 2021

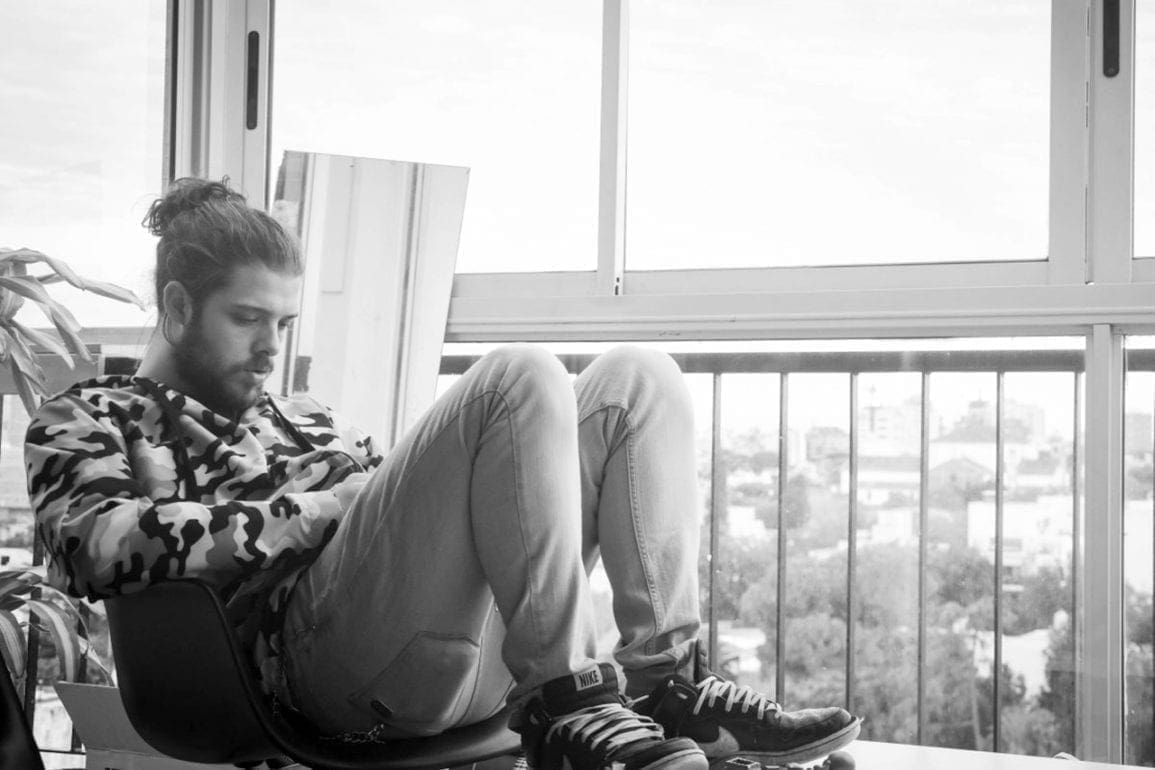

BUENOS AIRES, Argentina — I faced discrimination and fought to become the country’s first transgender head of nursing residency in Buenos Aires, Argentina.

To reach this goal, I faced my superiors, who called me a transvestite and said I lowered the status of the hospital’s hierarchy by occupying the position.

My suffering, however, did not begin on the job.

Tough childhood

My childhood was impossible. It hurt in school for my classmates to call me by my birth name, which did not match how I perceived myself. It made me blush and become embarrassed.

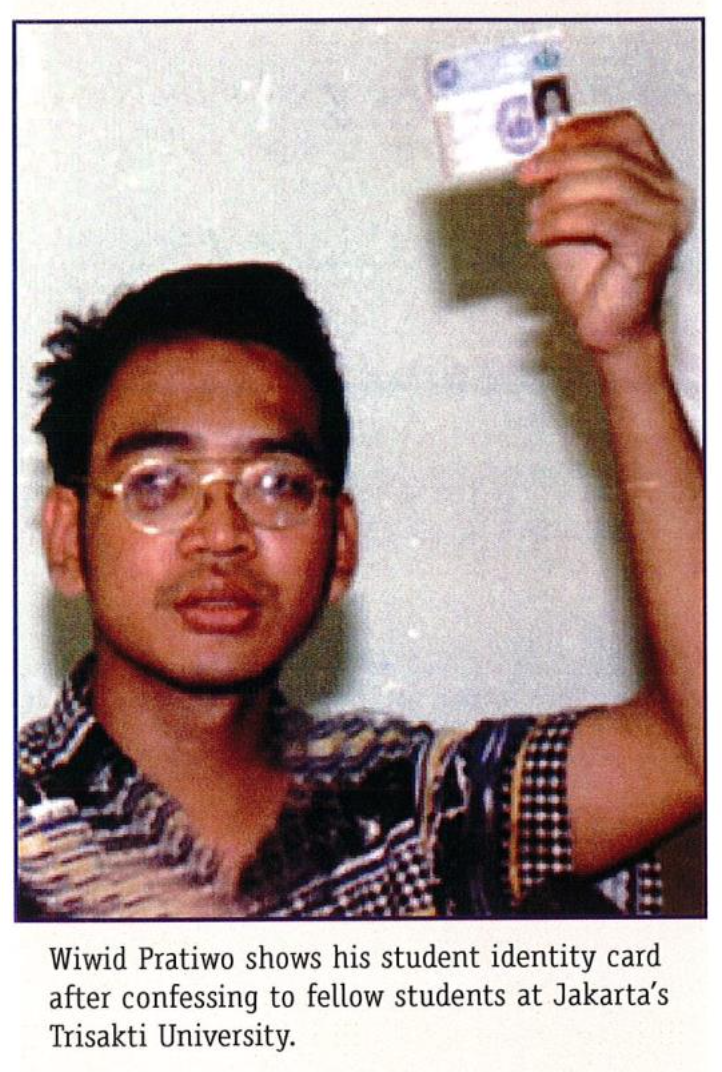

As I grew older, it became harder to handle those uncomfortable situations. When I would hand someone my official documents, they often looked at me contemptuously because the way I dressed didn’t match my name.

Eventually, I stopped going to medical appointments and doing paperwork. I dropped out of school several times until I finally finished high school at an adult college.

I immediately entered the infirmary, following in the footsteps of my sister Paula, with whom I share this vocation.

There, I competed with 200 nurses and finished among the top ten positions. This result allowed me to choose primary care as my specialty.

Despite meeting all the requirements, my superiors tried to stop my candidacy. The discrimination I seemed to escape returned once more to halt my dreams.

I pushed forward anyway and, finally, achieved my goal.

The law, my shield

Speaking about the difficulties in my life, I use the past tense. I had a tough life.

One of the steps I took towards inclusion in society was to change my gender on my official documents.

In 2012, in Argentina, the Gender Identity Law was enacted, and my life changed.

Thanks to the Law, I was able to get my new identification and finish high school – the place I had left because of discrimination.

Once my documents coincided with how I perceived myself, the teachers respected me, and there was a legal framework. They did test the limits. My teachers would, at times, use my last name, Esteban, to annoy me.

A changing world

What happened to me is news, but it should not be. Inclusivity should be a regular part of life.

Little by little, people like me are gaining more space, although the segregation of different groups still forces some people to the sidelines.

In the transgender community, we have been marginalized in all areas of our lives, including our work. For many of us, that means the only option left is to earn money through things like prostitution.

Part of the lower life expectancy for the people in my community is the lack of healthcare due to discrimination.

My role, help the community

One of my goals is to help the transgender community by creating campaigns to return to the clinics.

Today, there are no transgender patients who come to the health center. That is why I want to create guides for each of the spaces to know where they have to go.

In addition, I would like to motivate them to check-in for their vaccines, receive advice on contraceptive methods and sexually transmitted diseases, and obtain routine check-ups.

Currently, we have incorporated rapid testing of sexually transmitted diseases into follow-up appointments. This achievement gives me great happiness and pride because it reaffirms my vocation as a nurse every day.

I hope that my story is the first of many and that it is increasingly common for transgender people to occupy different vital positions in society.

I hope that more and more of us enter the public health system.