Kenyan mother grieves child stolen in hospital

Kenya has one of the highest rates of child trafficking in Africa, largely because of the vulnerability of the country’s young mothers.

- 5 years ago

August 23, 2021

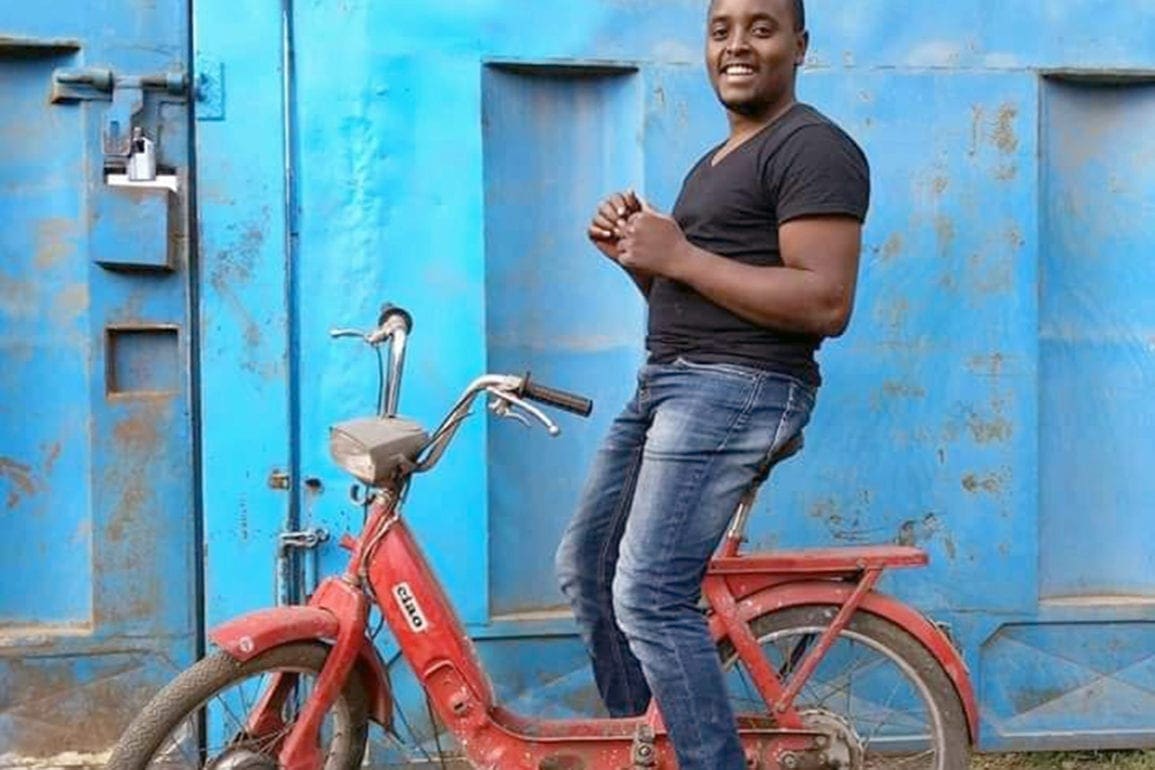

RUAKA , Kenya —I gave birth on June 4, 2018, at the government hospital in Kiambu County. We were discharged two days later, and I returned with my newborn son Nixon to my home in Ruaka [25 minutes southwest].

After two weeks, Nixon could barely move his bowels and when he did, he was in pain. I returned to the pediatrician where my son was born, but due to a nurses’ strike in Kiambu, they could not help me. The doctor referred me to a hospital in Nairobi.

My husband arrived at 2:00 p.m. to facilitate the hospital transfer. We hired a taxi, left the hospital, and traveled to Nairobi. While the drive is only 31 minutes south, due to traffic jams in the evening hours, we did not arrive until almost 7:00 p.m.

By then, the pediatrician had left, and we had to wait for another doctor on the night shift to arrive. Desperation set in, but my husband was patient and comforting.

At about 8:30 p.m., one of the nurses notified us that the doctor arrived and guided us to his office. A number of tests were carried out and they gave my son two injections.

Around midnight, the doctor informed us my son had no underlying conditions, but the severe constipation required medication to fully recover. He urged me to admit my son to the hospital for two to three days so that medication could be administered.

Without a second thought, we admitted my son.

Children housed separately from their mothers at the hospital

Nairobi is a vibrant city with public transportation readily available. My husband left the hospital and promised to visit the following day, while I stayed.

One of the nurses guided me to the ward but there was a complex rule in the facility that really baffled me. Mothers were kept in a different room from their children. We were only allowed to visit our children to breastfeed or to feed and wash them while changing diapers.

I questioned the nurse, “Why separate us? I want to sleep with my child.” She rudely responded, “This is the rule here and many other places. Explore and learn things.”

I was confused and asked her how I would know where to find my child. She explained, the child will be allocated a small, numbered bed, where he will be well covered and warm. She said I could visit him there.

I was taken to a room housing many infants in numbered beds, while others were in incubators. The nurses pampered the children and called their mothers when the need arose.

The good conditions, and the many young toddlers there, helped me to trust and accept the situation. They kept my little boy at bed 17 and I was taken to the general ward for mothers where I was allocated a bed too.

The rooms were not far from each other and there were no restrictions on how many times I was allowed to visit my son, but only five mothers were allowed in the infant room at a time.

I finally settled in and went to sleep at 1:30 a.m. I woke up at 5:00 a.m. to breastfeed my son. He was in good condition. While changing his diaper, he had gone to the bathroom, which made me feel great.

I went back to the ward to rest for another hour.

Newborn son comes up missing in hospital ward, nurses deny it

By this time, the facility seemed like a perfect place. I received a good breakfast, which is uncommon in Kenyan hospitals. The day continued and I regularly visited my son. I fed and changed him, while the nurses administered medication.

I communicated with my husband by phone to reassure him everything was well and there was no need to panic. He returned at 4:00 p.m. to check on us. The first day ended well, and we had two more days to go.

Then, on August 3, I experienced the most painful day of my entire life. It was the evening of the second day. At 8:40 p.m. I woke up in my bed and went to the infant ward to check on my son.

I went to bed number 17 and found a child that was not mine laying there. My son was only a month old, but I knew what he looked like. He had his father’s creamy hair and chubby face.

“Nurse, help me,” I yelled out in a panic. Other mothers who were close by came first, thinking the child had developed complications.

“What’s wrong,” they asked. I didn’t reply and started crying out, “I need my child.” The nurse came in angrily and ordered everyone out for causing a disturbance. The nurse instructed me in a harsh tone to be silent. I would not.

“I want my child. This is not mine. Give me my child, please,” I pleaded. One of the nurses tried calming me down, which worked for a few seconds, and I was able to make them understand someone had taken my child and placed another one in his bed.

They thought maybe the child was still in the room but in a different bed. I was taken through the beds but did not see my son, I screamed louder and the nurses resorted to forceful claims that I was in shock my child was very sick.

This was an attempt to calm the other mothers who had started questioning what was happening.

I urged them to allow me to call my husband. They resisted at first, but eventually agreed. My husband thought I was going crazy and tried calming me down. He thought I was confused and doubted me, but he promised to come to the hospital.

The child who had been placed in my son’s bed went unclaimed after two hours. Whoever stole my little boy organized the perfect crime.

DNA results confirm that an infant was kidnapped and trafficked

When my husband arrived, he looked very somber and confirmed to the management that the boy in bed 17 was not our son. He demanded answers.

The management was reluctant to cooperate, so my husband rushed to the police station. At 11:00 p.m., Kenyan police officers arrived at the hospital. By then, I had passed out and later learned I was sedated.

The hospital claimed they sedated me to calm me down and avoid distracting others at the hospital. The police took a statement from my husband and requested to see the CCTV footage from the hospital cameras.

Despite all of this, the police said the matter could not be handled overnight. I had to record a statement the following day to begin an investigation.

The next day the police assured us that we would get our child back soon if he was indeed stolen.

The child who was placed in my son’s bed added a twist to the crime. The police wanted DNA samples to ascertain if he was our son. They requested pictures of our baby, but neither my husband nor I had smartphones or pictures of us with our son.

The thieves must have observed me to determine I was a good target, likely due to my poverty. I feared that since corruption continues to be a huge problem in Kenya, that the hospital management and police were delaying the invitation to manipulate the results.

We did not want the hospital conducting the DNA test, but we could not afford a private test. I was in utter despair, but my husband remained so strong.

If we had money, we could access the media or famous personalities to help us. Locals offered to post on social media sites, describing the lost infant, and those posts went viral, but my son was not found.

The DNA results were hurriedly released three days later and were negative. The boy in the bed was not my son. With media pressure mounting, the police confirmed this was a case of child kidnapping and trafficking. The hospital, though reluctant, finally admitted the child was lost while in its care.

No answers for grieving mother

There are so many unanswered questions. How did an infant leave the children’s ward? Why was the kidnapper never caught on camera? Where were the guards and nurses? Who is the child that was placed in bed 17 and why was he left behind?

Eventually, the mystery child’s parents were tracked down. His mother was a street beggar. It became clear the child was used to facilitate the kidnapping of my son, and that a desperate mother was paid to use him.

Replacing my son with another child was a means to walk from the hospital freely and delay anyone from noticing a child was missing for several hours.

The police continue to pursue the case. The kidnapping was a major blow to the hospital, but it continues to operate.

I gave birth to another son on September 3, 2020. He is a comfort to me, but I continue to look for Nixon. I visit media offices and organize rallies but nothing has changed in three years now.