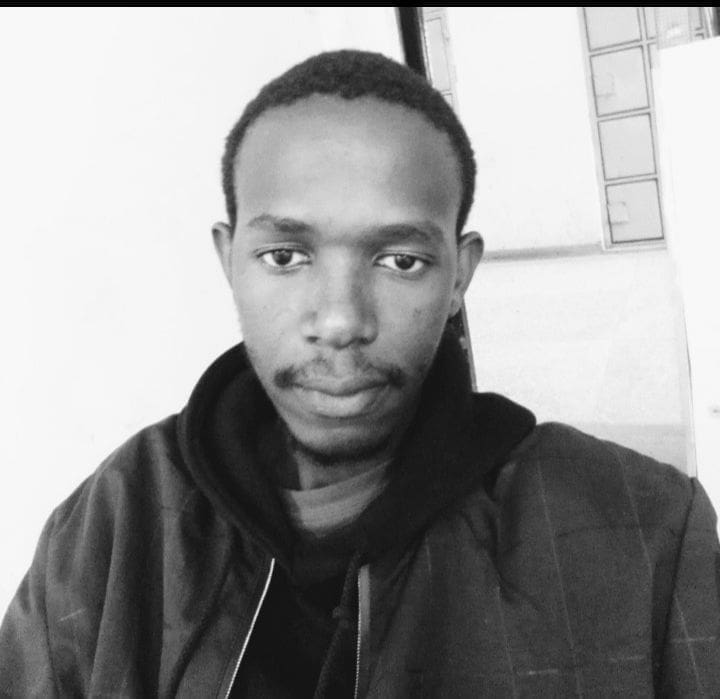

Fashion designer from Kenya slum danced to pay for fabric, featured in Vogue

After some of our dancers were mistaken for thugs and killed, my mom urged me to pursue something else. Today, my fashion designs have been recognized by Beyonce, Bruno Mars, and other celebrities.

- 2 years ago

June 6, 2022

NAIROBI, Kenya ꟷ Born and raised in Kibera slum, my single mother cleaned and took odd jobs to support me and my siblings. As a sponsored soccer player, I paid for school fees, but lack of finances eventually forced me to drop out. Despite our challenges, I pursued my creative passions. Today, I am a leading fashion designer in Kenya.

The struggle from high school dropout to trained fashion designer

In high school, my soccer sponsorships dried up and I stayed out of school for months. With my free time, I started a dance crew. We practiced every day in Kibera, dancing and offering spoken word performances. Many young, desperate people in the slum lose their lives to drugs and crime. We spoke out at events, weddings, and political rallies. The money I made helped my family.

We dressed in hip clothing and donned dreadlocks. Soon our dancers were mistaken for thugs. Some were killed. A fear rose in me as my mother urged me to pursue an alternative means of survival. Self-reflection consumed me for months.

Having built up a savings, I took the money and enrolled to take the final high school examination. Busy trying to work and support the family, I did not prepare enough and disqualified for university. Enrolling in a technical course proved to be my only remaining option. I persisted.

After practicing with local tailors doing clothing repairs, in 2015, I applied for a scholarship at the Buruburu Institute of Fine Arts through the Maisha Foundation. Hopeful, I presented a series of costumes I made. The panelists liked my work enough to select me. In a year’s time, I learned costume design and marketing, and earned a certificate in fashion design.

Early fashion designs in Kenya create foundation for future success

Back in Kibera, I faced continued financial struggles, working hard just to raise enough money for a sewing machine and fabric. Though hope seemed to dwindle, one day Ken Okoth, a former member of parliament, gave me a sewing machine! My career in design began that day.

Soon after, a friend gave me space in his workshop. I danced to finance the materials I needed for my tailoring shop. Early on, I made shirts for my dance crew. In the capitol of Nairobi people praised our shirts and I experienced a sense of accomplishment. People saw my work as brilliant, and motivation swelled inside me.

History matters and my designs reflected the Kenyan culture. The diversity of the 42 tribes of Kenya combined with foreign influence weaved its way into my vision. I became particularly inspired by Kenya’s vibrant Luo culture and traditional Maasai Shuka fabric.

Avido fashion recognized by Beyonce and Bruno Mars

Filled with gratitude, I designed clothing for Ken Okoth who gave me that first sewing machine. By wearing my clothes to Parliament, he marked a turning point in my career. He became my brand ambassador, attracting celebrities to my work. Those who rose from the Kibera slums also promoted my work.

Then, legendary reggae artist Don Carlos came to perform in Nairobi. I approached the event organizers and asked if I could make him a custom designed shirt. They said yes! When I presented the shirt to Carlos, he made me a promise to partner with my brand. Suddenly, new doors were opening internationally. I began working with artists and designers outside Kenya – artists like Romain Virgo, Usain Bold, Bruno Mars, and Christopher Martin.

Avido fashion wear really took off after that. A call from a friend left me speechless one day. Musician and fashion icon Beyonce recognized Avido by listing us at that time in Beyonce’s Black-Owned Business Directory. I felt my shop was fully established.

Giving back to the families in Kibera slum

I know how tough life can be for the people of Kibera slum in Nairobi, Kenya. I lived that life from a young age, so I made a deliberate decision to locate my workshop near Kibera.

My tailors provide training to young men and women interested in fashion design; and we mentor young people. We provide uniforms to students in need and relief to their families. Using my success, I dream of offering young people in Kibera an alternative to the life of crime and drugs they pursue out of desperation.