In one of the world’s toughest prisons, he cofounded Jail Time Records

That evening I sat in the corner of the cold, stinky cell, seeing fellow inmates who refused to bathe and suffered from strange skin diseases. It dawned on me; this was my new reality.

- 1 year ago

February 2, 2023

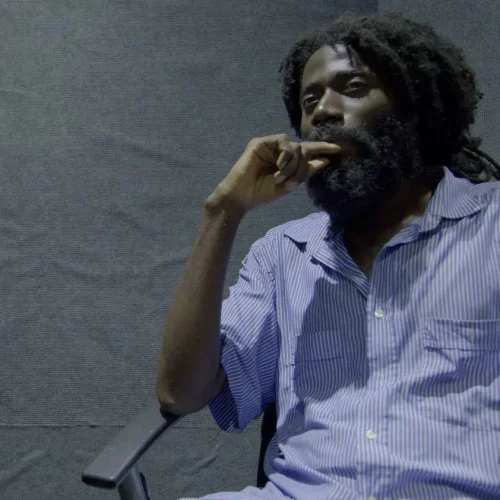

DOUALA, Cameroon ꟷ In 2018, after my father’s sudden death, my two brothers, cousin, and I got arrested and convicted of his murder. The judge later found us not guilty and released us from prison. After accessing a music studio in jail, I began documenting the stories of my fellow prisoners and making music day and night. Throughout the process, I became co-founder of the non-profit project Jail Time Records.

Read more prison stories from across the globe at Orato World Media.

In Douala Prison, they ganged up on me quickly

After spending four years in Casablanca, Morocco pursuing a degree in International Business Management at Sunderland University, I decided to go back home to Cameroon. Little did I know I would face the greatest challenge of my life. As I continued studying at a university back home, my father died suddenly.

My dad’s family held the traditional beliefs of our kinsman, but my brothers and I were Christians. We wanted our father to receive a Christian burial. This sparked a major controversy with the rest of the family. My paternal relatives insisted on a traditional burial, including my dad’s younger sister who served as a judge in Douala. Sadness consumed me.

The family quickly ganged up against us and with my aunt’s power and connections, the justice system began applying pressure. They claimed we refused the traditional rituals to avoid having the corpse examined. Of course, this was untrue, but it led to our arrest. We arrived at Douala Prison – one of Cameroon’s toughest prisons – at night and the walls closed in on me. From my first minute there, I felt scared and irritable.

I could see the strong, scarred faces of people behind the bars as they yelled things like, “We gonna kill you.” They hurled insults and I felt like a character in a movie, moving through the darkness surrounded by demons. For hours, they continued yelling. A man punched me in the back to measure my weakness and intimidate me. Before I knew it, they robbed my t-shirt.

That evening I sat in the corner of the cold, stinky cell, seeing fellow inmates who refused to bathe and suffered from strange skin diseases. It dawned on me, this was my new reality.

I was dying inside so I started documenting the inmates’ stories

It did not take long for family members to begin arriving, attempting to coerce us into accepting a traditional burial for my father. My brothers, cousin, and I stood our ground. My dad’s body lay in a morgue for two years. It tormented me, and I needed to do something with my time.

A friend of mine knew one of the prison administrators so I asked him to speak on my behalf. I wanted to have a computer to make music. He introduced me to the administrator and on my second day there, I walked confidently into the office full of hope. I learned that the prison had a music studio under construction, but it could be a while. He would want my help when the space became available.

The waiting shattered my spirit. I need something to keep me from overthinking. It felt like every second I spent in the cell, my soul died slowly. Rather than going back to the administrator, I decided to focus on something new. I dove into writing stories. Each day, I sat and listened to the inmates tell me about their lives – how they got to prison and how they stayed strong. Their words devastated me.

Most of these men grew up in prison, coming in and out. Many addicts committed crimes under the influence of drugs. They stole money and bullied people to feed their habit. We had a drug addiction problem going unaddressed. So each day, I continued writing their stories until one day, my friend told me about a Caucasian lady who sometimes visited the prison. He said she was the person building the music studio. I wanted to meet her.

My body remained in jail but my soul became free

When I met Dione Roach, who volunteered through the Italian NGO Centro Orientamento Educativo – she gave me the keys to the studio. Although still under construction, she let me in, then she left the country for a while.

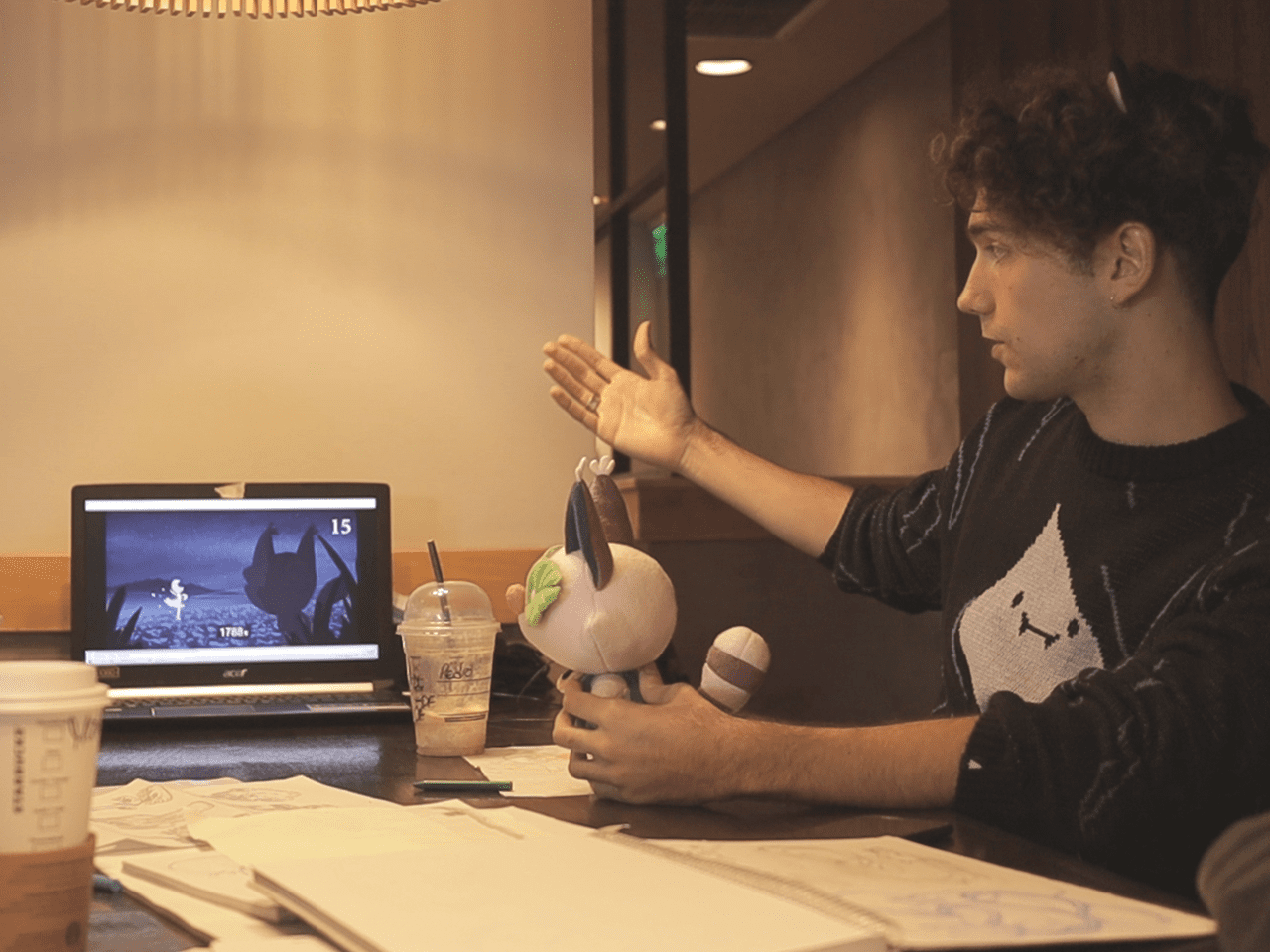

I started making music day and night, and sending her my backtracks. When she returned a couple months later, we began shooting videos. I recorded more than a thousand songs. Discovering this outlet made me feel free of my sentence. I stopped counting the hours, minutes, and seconds of every day. In prison, you always think about getting out. It consumes you.

Now, I was recording people’s stories into songs. Sometimes, I spent so much time in the studio I barely slept or ate. My body remained in jail but my soul became free. I thank God for that and for Dione, the NGO, and the jail administration.

During the countless hours in the studio, I discovered a new side of music. It became an instrument of resistance for a new hope and it connected souls. I listened to other people’s stories, and even my own. Music allows you to know people more deeply. The things they cannot say directly, they can speak through song. As the person doing the recording, I got to hear countless artists come in, and learned so much from them.

Sadly, many return to their way of life, but some come out and make life better

Some days, I looked around and saw my colleagues breaking down emotionally. Witnessing their pain, I learned not to judge people in prison. Some went through incredible mistreatment as children. I got curious. What was your life like? Why did you commit your first crime? What triggered this life? Listening to their answers, I witnessed frustration, parental abandonment, lack of love and attention, and poor influences.

Right then and there, I decided my work with these prisoners would be a form of healing – for me and for them. I wanted to offer hope and stability. For two years now, I worked with over 100 artists in prison. Sadly, many of them return to their way of life upon release. A few, however, reach out and we continue making music.

After leaving prison, we launched Jail Time Studios from the outside. We had to. For many prisoners who got released, it proved too much to go back into the prison to record. Since my release in 2019, at Jail Time Studios, I have recorded over 500 songs. We just released our first album – Jail Term Vol. 1. The genre weaves together a 22-track compilation celebrating the unique perspectives of the artists.

In my song LOVE, performed in my Kweni dialect, I offer a message to my family, urging reunion since my father’s passing. Now, in 2023, we fight to grow this project, expanding it into Ouagadougou Maco Prison, known as Burkina Faso. One day, we hope to grow into prisons across Africa and throughout the world.