Woman in Argentina discovers midwives sold her at birth

The stories came to life for me, listening to the testimonies of the victims. Parents woke up to find their babies stolen. One person said, “I heard my baby cry, and they put me to sleep. I woke up three days later and they told me that my baby had died.”

- 2 years ago

August 6, 2022

BUENOS AIRES, Argentina ꟷ As a newborn baby, a midwife took me from my mother, sold me to my adoptive parents, and forged my birth certificate. I may never know who I am and where I came from.

I became a victim of Las Parteras del Horror (The Midwives of Horror) in Argentina. Some days, my situation feels desperate.

Baby sold to adoptive parents by midwife

At 14 years old, my parents told me they adopted me. I did not see the files or paperwork on my adoption, nor did I ask. The possibility of identifying my birth mother and father remained elusive, because my identification papers listed the couple who raised me as my biological parents.

While my birth certificate says July 6, 1979, I learned that date may not represent my actual birthday. The certificate further lists my birth location as an apartment in Buenos Aires, Argentina, the home address of a midwife. The woman at the address has since been identified as part of a group of midwives who appropriated children at birth and sold them to adoptive parents. These parents recorded the children as their own on fake birth certificates.

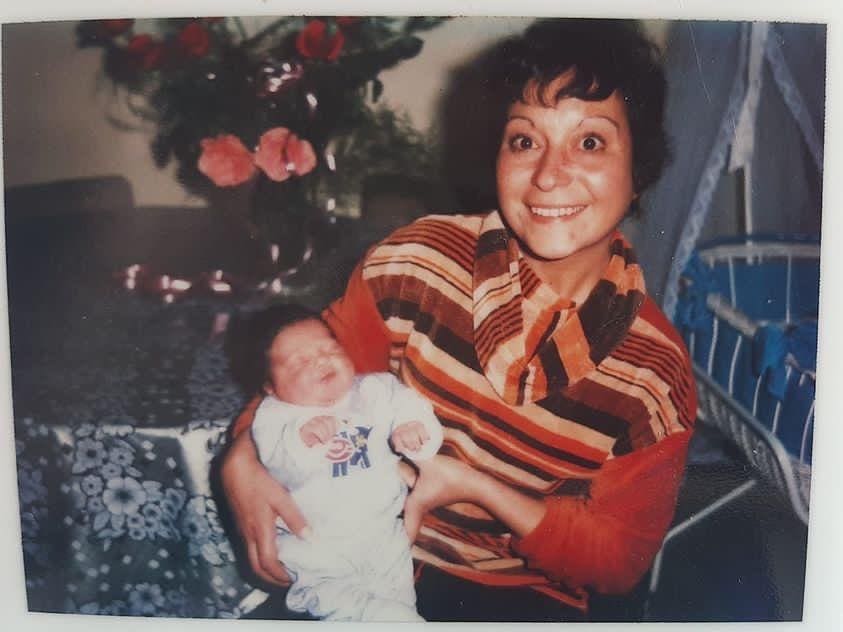

Few photographs exist from my birth. One shows my adoptive mother Nelly holding me in her arms. A bouquet of flowers on the table marks the celebration of my arrival. Behind it, a light blue cradle matches the color of my newborn clothes.

Commonly at that time, in the 1980’s in Argentina, girls strictly work pink, and boys wore blue. I inferred from the photograph that they expected their new baby to be a boy.

Woman discovers she was part of a larger trafficking ring

My adoptive mother Nelly passed away at the age of 30 and I approached CONADI (The National Commission for the Right to Identity). It never occurred to me to start my research while Nelly lived. I did not want to cause her pain.

CONADI conducted DNA testing and asked questions. My date of birth matched a time of military dictatorship in Argentina, which gave me special access to a DNA database.

Unfortunately, after three months, the DNA results came up without a match. All my expectations were dashed when I received that fleeting, distressing phone call. At a transcendental moment in my life, I had no support and no one to accompany me. I suspended the search.

Last year, in mid-August, I found a group called “United Victims of the Midwife Network.” They welcomed me warmly and guided me through a series of steps all seekers must take to start their search. Suddenly, I came face to face with an unexpected reality.

I learned that along with more than 150 other people, I had been a victim of baby trafficking from an organized group of approximately 14 midwives. They maintained an illicit partnership and worked in a specific area of Argentina with different hospitals, doctors, and government organizations. It took me a very long time to process that fact. Learning I was part of this group felt like a slap to my soul.

I have taken three different DNA tests – one from CONADI, one from Family Tree DNA out of Houston, and one from a Brazilian company called Gen Era. The closest match I obtained came from a second cousin. The process of investigation feels very complex.

Midwives stage infants’ deaths

I learned the midwives targeted couples who could not support their children, as well as very young pregnant girls who believed they could not keep their babies. The midwives used lies to convince these mothers to sell their babies for cash.

Mothers now connected with our organization recount being told, “We are going to give that baby a home and a family. On the other hand, if you keep the baby, he will meet a horrible fate.” Sometimes they even told the mothers their baby died. Taking advantage of their pain and shock, the midwives said they would take care of everything. This allowed them to withhold death certificates and never show the grieving mothers their babies’ bodies.

The stories came to life for me, listening to the testimonies of the victims. Parents woke up to find their babies stolen. One person said, “I heard my baby cry, and they put me to sleep. I woke up three days later and they told me that my baby had died.”

While this is not the only network of midwives taking babies from their mothers, we now understand how these networks work. In my case, my adoptive parents took the birth certificate the midwives gave them to a federal organization and registered me as their biological daughter.

By doing so, I lost the ability to know who I am. Even though my birth certificate remains illegal, a public, government body validated it.

The emotional toll of searching for one’s history

The midwives who victimized me – the Parteras del Horror – worked in collaboration with other organizations and professionals beginning in the 1950’s. They continued until they were discovered in the 1980’s. Our search for our families, and our collective fight, helped extend the law of identity origin in Argentina. The new law proposes to gather and give access to a broader genetic bank because, in our country, the only bank we have is limited to a specific period of Argentine military dictatorship.

With the law extended, anyone can take on a case to search out their origins and it will no longer be limited to that moment in history. Today, those of us involved in the fight, encourage anyone who worked with a midwife, who was told their baby died but do not have a death certificate, to contact us. Ancestral DNA can be examined in a global database now.

Taking on this process does prove difficult. Not just the steps, but the mental impact of making the decision to search, can be hard. When I ordered my DNA test online, it arrived in three days, but it took me three weeks to gather the courage to do it.

The swab proves less invasive than a COVID test but engaging it can stun you emotionally. Many of us suffer from guilt because we do not want to hurt or harm our adopted families, but we need to try. We must find our identities if we can.