Mexican saxophonist endures near fatal acid attack, returns to the stage

I awoke after the acid attack locked down and motionless in a hospital bed, an oxygen mask attached my face. I had been sedated due to the severe pain throughout my body. I was on the verge of death.

- 2 years ago

June 10, 2022

OAXACA, Mexico ꟷ In September 2019, my ex-partner attacked me with sulfuric acid in an attempted femicide [the intentional murder of a woman for being female]. Third-degree burns damaged 85 percent of my body.

Since that horrific event, I began playing music as a tool to demand justice and fight violence against women in Mexico. The most precious thing in my life is my freedom, and music makes me feel free.

Women attacked by acid nearly dies in Mexican hospital

I awoke after the acid attack locked down and motionless in a hospital bed, an oxygen mask attached my face. I had been sedated due to the severe pain throughout my body.

Terror is the best word to describe seeing your body’s skin burnt and rotting, with so much damage you can distinguish the nervous tissue. I was on the verge of death.

This wasn’t the first time I experienced patriarchal machismo in Mexico. From the age of eight, I began my journey with music, playing an instrument in my town’s orchestra. In our rural community, the municipal band is a source of pride, playing an important social role.

Being the youngest girl there and the most diligent, the men became irritated and annoyed. I could not look better then them, so they kicked me out of the band, forcing me to leave music behind for a few years.

Later, as a college student studying communication sciences in the state of Puebla, I resumed and began to formally study music. Once again, harassment came. Male teachers gave high grades to women who agreed to their “requests.”

Music brought suffering and in the hospital bed all these years later, I cursed my parents for taking me to that municipal band as a young girl and starting me on this path. I believed music nearly killed me.

Victim of attempted femicide shuns music during recovery

The attempted femicide left me with scars everywhere. The lengthy and numerous treatments proved painful and frustrating. Recovery moved slowly, and at some stage, became exasperating. Before the attack, I was a very active woman who enjoyed traveling, playing, and teaching music. After the acid attack, when I thought about music, I believed I would no longer be able to play.

I doubted my life had any meaning and thought little about ever playing music again. I did not know music would be the very thing that rescued me.

After leaving the hospital, the guitarist Pato Montes from the group Maldita Vecindad contacted me to see how I was doing and offer support. Bewildered and upset by what happened to me, they urged me to keep playing. They suggested music could help me overcome the experience.

I did not feel like moving forward at that time. With my body covered in scars, I thought I would never play in public or in front of people ever again.

Mexican saxophonist rises from recovery to take the stage

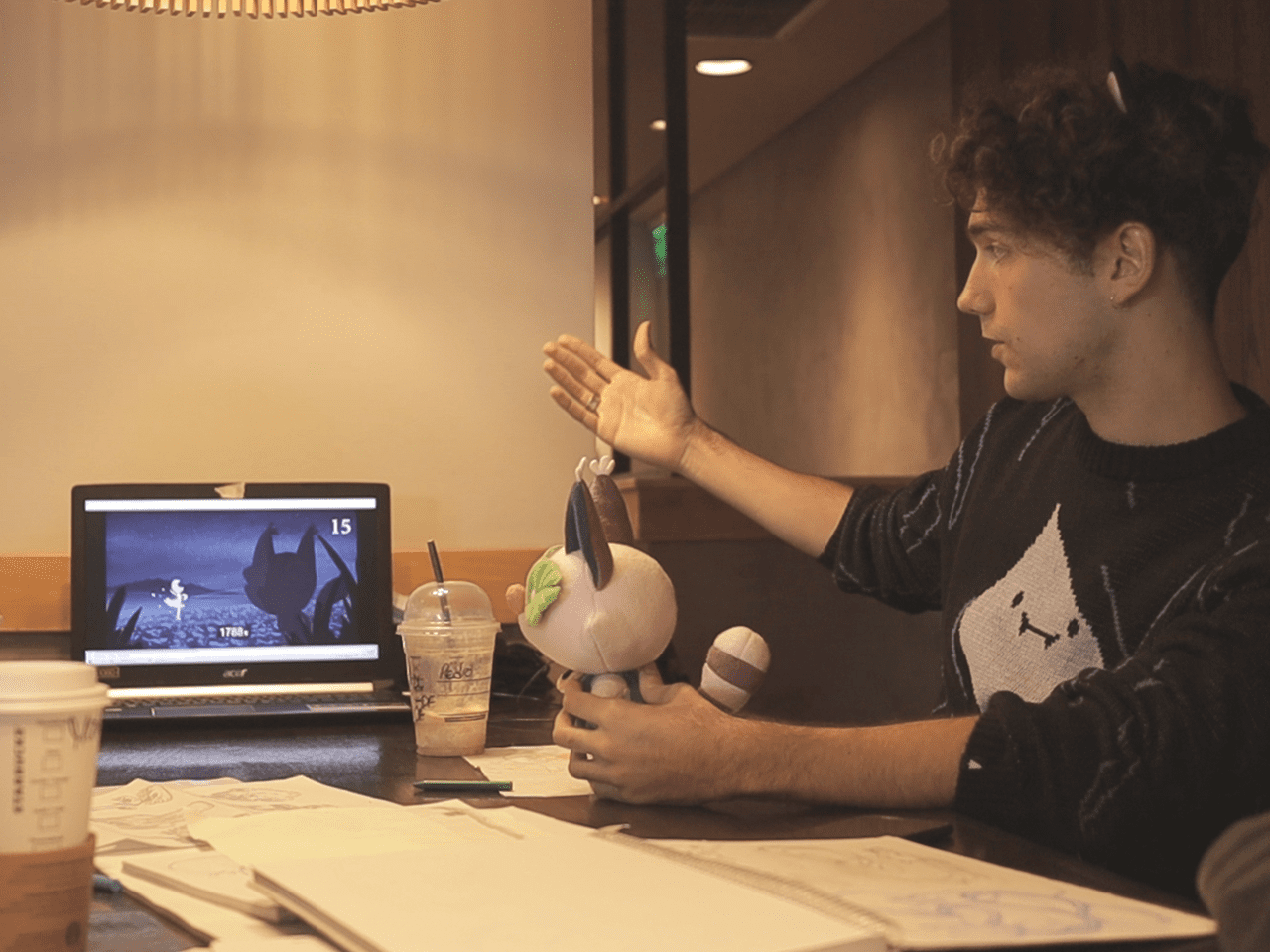

At the peak of the COVID-19 Pandemic, I took an unexpected step forward. I agreed to collaborate remotely on a very careful video of the song Chacahua where my face would not appear.

The song was named for a wonderful beach in the Oaxaca state with a freshwater lagoon that shines at night. The band approached me purposefully, intending to encourage me, help me feel the music again, and internalize that I am still an artist.

As a saxophonist, I could not play very well because the scars on my mouth interfered. The acid attack caused my mouth to stay practically closed. The doctors opened it little by little with surgeries, until I could play the saxophone again.

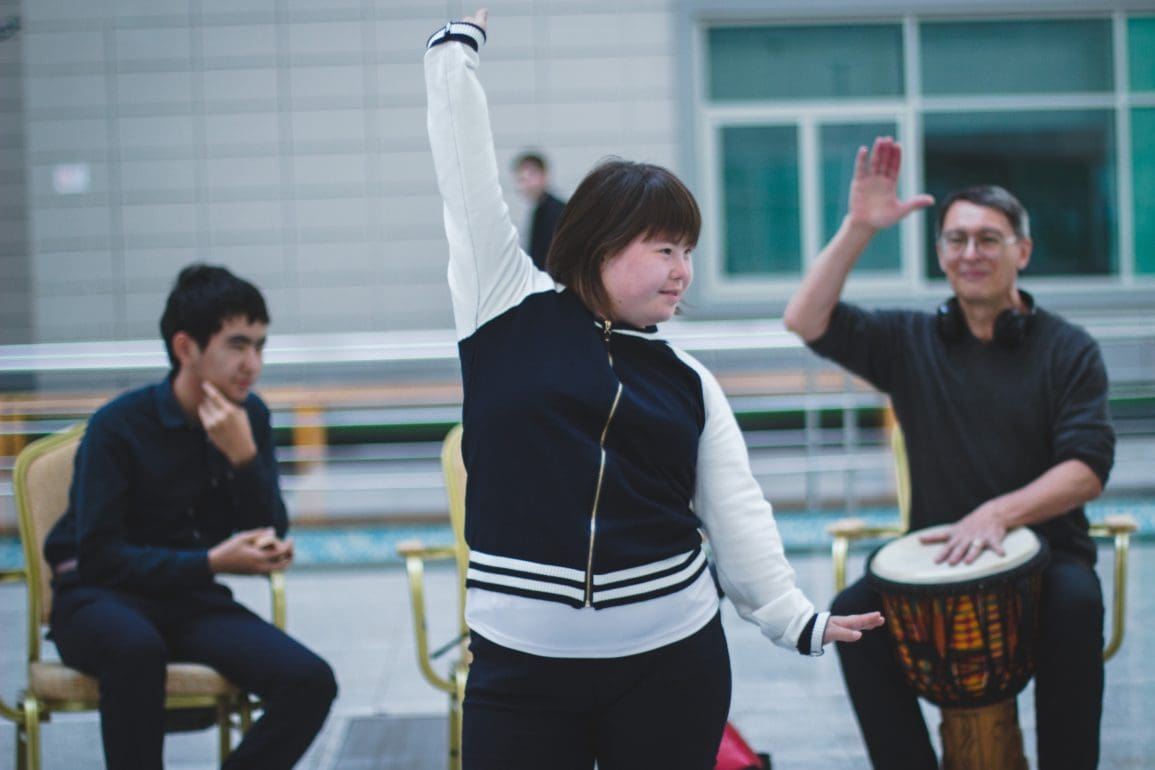

Seven months after the attack, I finally played live. The famous Mexican singer Ximena Sariñana asked me to join her on live television news. I accepted and began recovering the embouchure [the way in which a player applies the mouth to the mouthpiece of a brass or wind instrument] of the saxophone.

The process proved complicated. I was unable to hold the application at first, but with effort and commitment, I began to play. In doing so, music once again allowed me to feel free and alive.

Musician experiences the greatest moment of her life

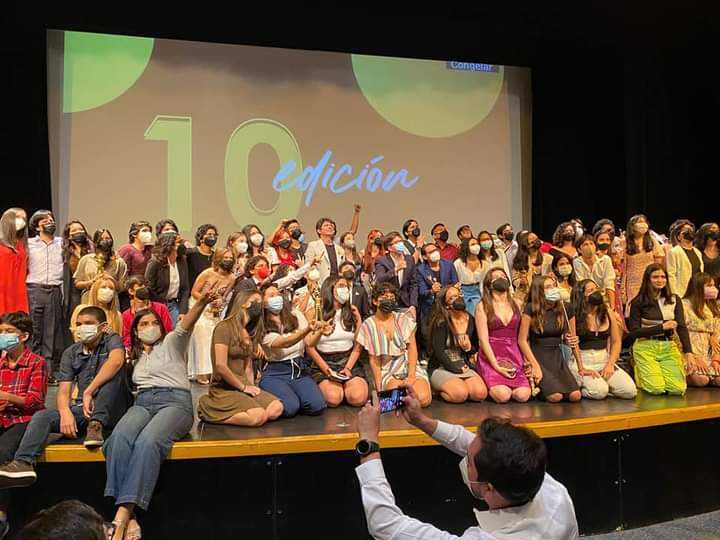

I continued appointments for medical interventions, dermatological treatments, and rehabilitation exercises. As I healed, I dedicated myself to other women fighting to defend their rights in Mexico. Opportunities came.

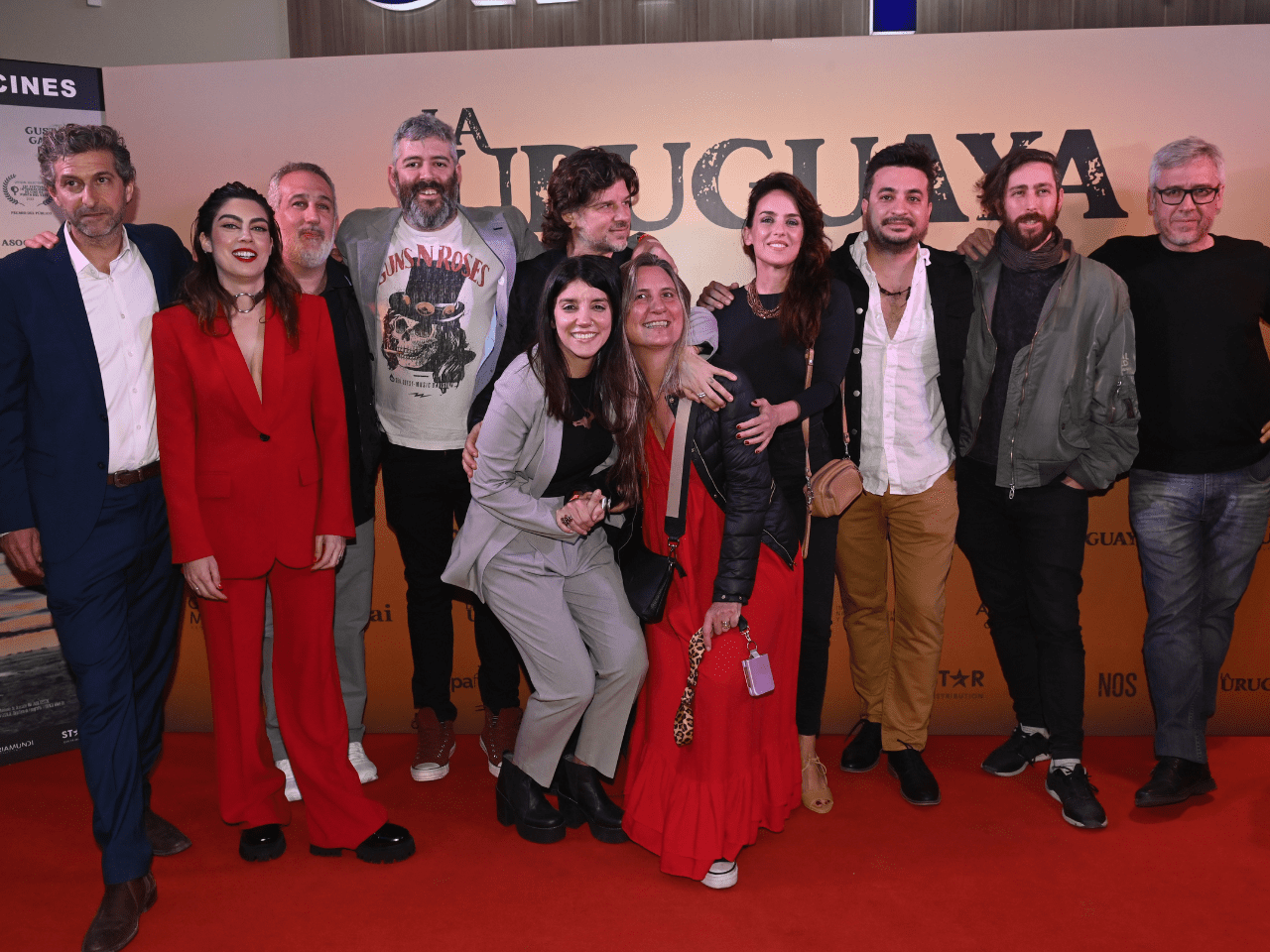

When I had the chance to play in Vive Latino with Maldita Vecindad – one of the most emblematic, traditional bands of Oaxaca – I experienced an ecstasy of melody. I never imagined I would play with them, much less on their famous song Kumbala.

Though nervous, the public supported me. They reacted to my presence in a very human way, and I felt their sisterhood. Onstage, I felt like I was flying as I watched people laugh and dance to the music. It was one of the greatest privileges of my entire life.

On that special day, I wore an acid green dress. Even though men tried to kill me with sulfuric acid, seeing myself on stage in green gave me life. It was as if my spirit left my body for a moment and spread out amongst the people. That feeling of being more alive then ever stays with me and fuels my desire to take on the legal tasks in front of me.

Music becomes a fighting instrument for women in Mexico

The only weapon I have, to achieve justice, is music. It has a way of making reality visible. It reveals problems, denounces abuse, and exposes injustice.

Today, I am beginning to understand why I lived. The problem was never me; it is the existing patriarchal machismo permeating Mexico. Women like us have always lived in this culture but now, I dedicate myself not only to recovering, but living my life well every single day.

Our society in Mexico is extremely misogynistic and sexist. Attacks against women get justified and the women are blamed.

Music has become a tool for me to fight against violence, to echo other women who suffer abuse, and whose cases no one knows. I play for the women who are invisible to society and who go unseen by the authorities.