German resident, dance instructor trapped in Gaza for 75 days works with children affected by war

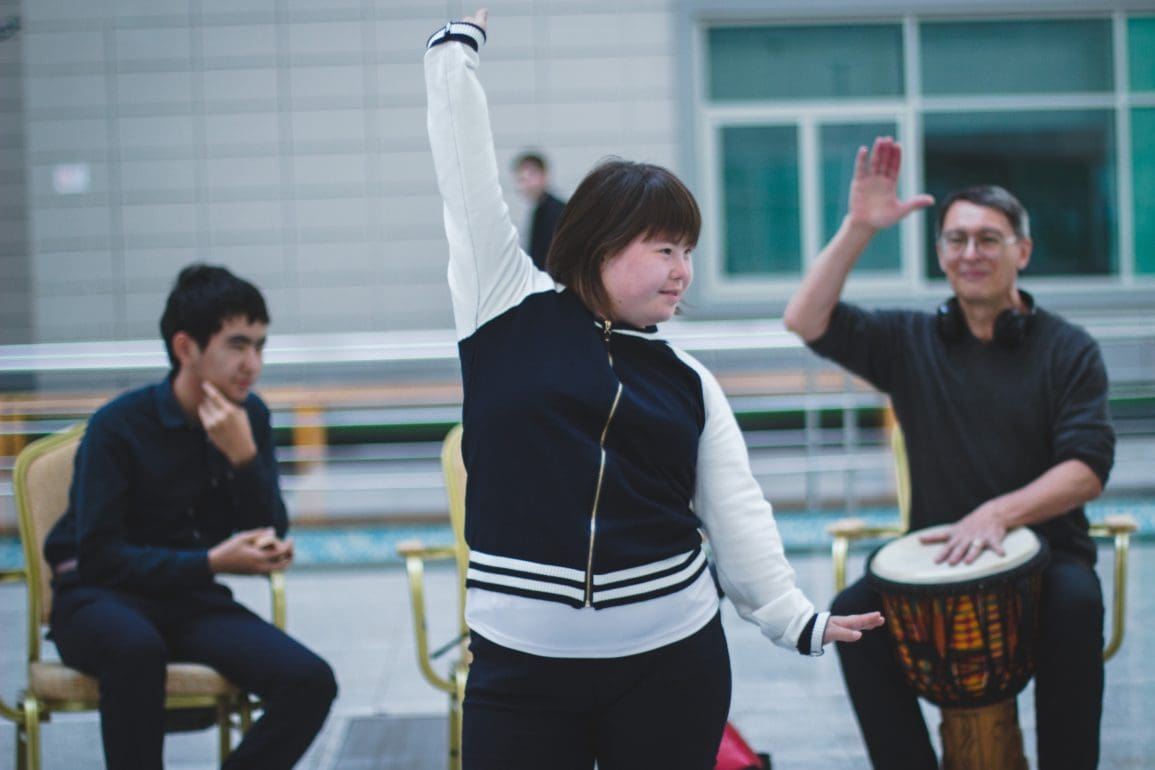

As an emergency trauma counselor, educator, and a dance therapist, I knew exactly what the situation demanded. Our dance school became a refuge for the children. They arrived, eager to use our special handshake and start dancing. While I felt afraid, I smiled to give them hope.

- 4 months ago

July 9, 2024

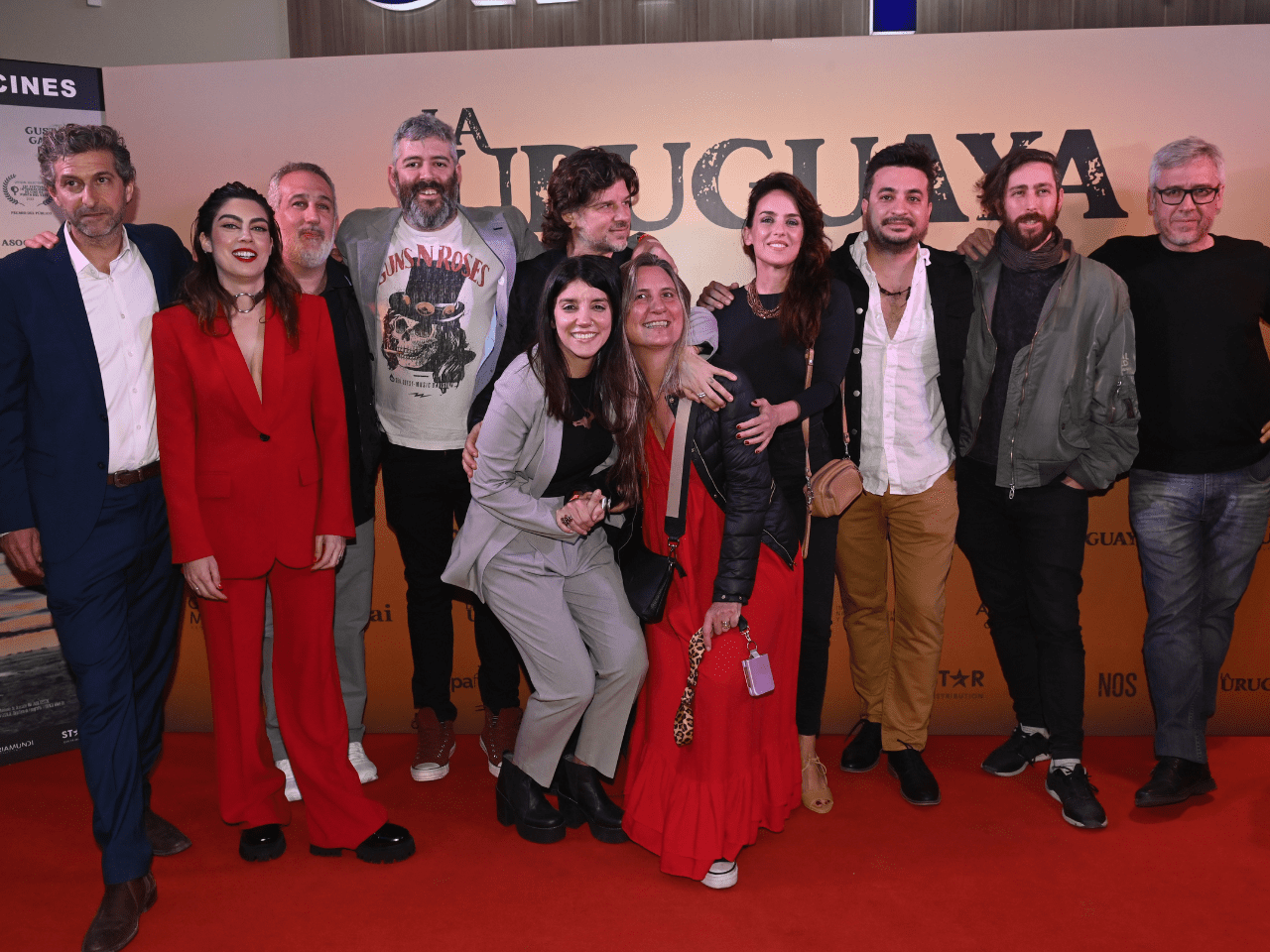

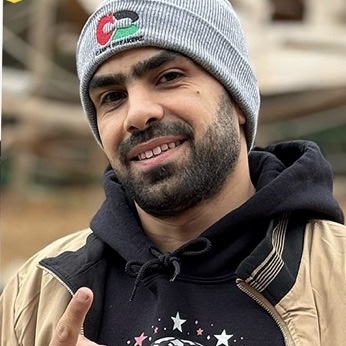

GAZA, Palestine ꟷ My colleague Azzam and I boarded our flights to Gaza in August 2023 for our yearly dance event, full of hope. Nearly two decades earlier, my brother Moh Ghraiz (Funk) and I founded the group Camp Breakerz to train generations of dancers across Palestine

From August through October, we made incredible progress toward our goal and began to prepare for the 2023 production themed “Still Alive.” We selected this theme because of the difficulties Palestinians faced for years.

Azzam and I never anticipated being stuck in Gaza for over 75 days with no way to leave. Under constant bombardment and intense fear, we continued offering the children of Gaza hope and happiness through dance. It is not our first-time witnessing war, but after October 7, 2023, the scale of what we witnessed will stay with me forever.

Read more stories from Gaza at Orato World Media.

Special days of dancing in Gaza soon turned to horror

Every year, I travel to Gaza with my colleague Azzam to teach children to dance. Since 2004, the Camp Breakerz program impacted the lives of Palestinian children affected by conflict. I travel from my home in Germany. In 2018, when Azzam moved from Gaza to Egypt with his family to study, he began traveling with me.

For decades, I thought it was a miracle to wake up in the morning in Gaza given the conflict and suffering between Palestine and Israel. I often kept our Instagram fans updated on whether we were alive or dead. When we boarded our flights in 2023, we knew Hamas had been resisting but we never anticipated the attacks that took place on October 7.

That very day, we planned to decorate the stage for our show. On the eighth, we would host our last rehearsal. The two dance groups we trained would come together on one stage in preparation for the event on October 9, 2023. However, when we awoke on the eighth, we heard the sounds of bombs and rockets. I could barely comprehend what was happening. I wondered, “How could this occur on our important day?”

Hoping to move forward anyway, we prayed for the noise to stop. We had more decorations to arrange, rehearsals to hold, and costumes to pick up. When the children arrived at the dance school, we had no idea what to say to them. Sadly, we had no choice but to cancel our activities for the next five days. We could not even hold classes. Feeling the weight of shock, we switched into survival mode. We organized food and water to prepare for the coming days and weeks, uncertain how long the bombings would last.

We decided to head to the Nuseirat refugee camp to help children at the school

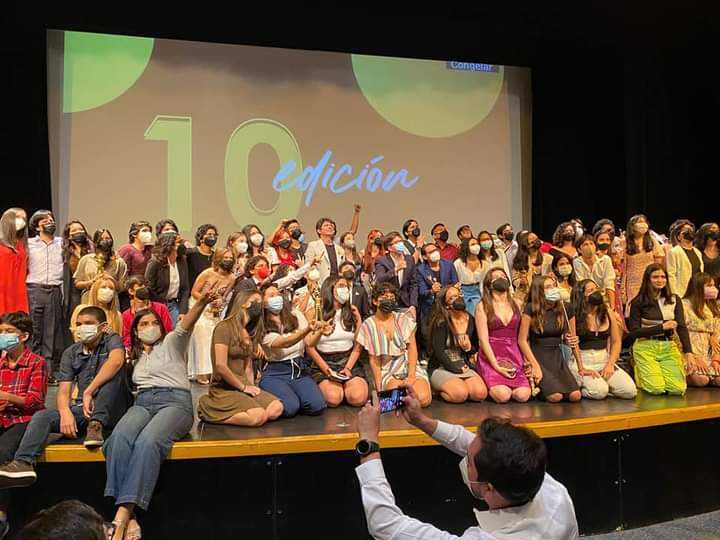

As the situation in Gaza worsened, I felt a strong urge to use our creativity to support and stabilize children in the conflict. On October 12, Azzam and I went to a UNRWA school at the Nuseirat refugee camp. We asked the school manager if they accepted people like us to work with the children.

The director responded by asking, “Where have you been? I have been looking for people like you.” By this time, the teachers abandoned their roles to help manage the growing number of displaced people in Gaza. The same day, we started our activities at the Nuseirat refugee camp. For five days, we engaged the children in dance.

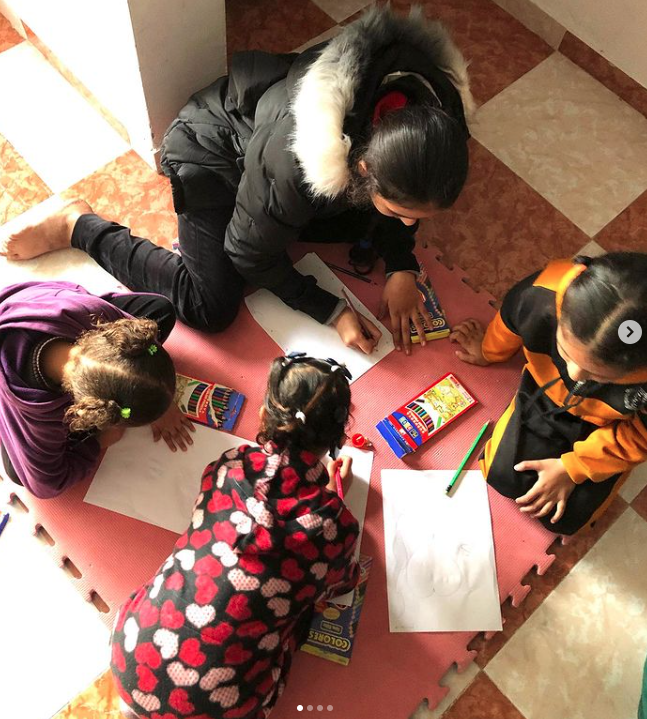

I felt their energy and joy as I watched the children smiling again. Seeing their faces refreshed me. At times, we gave them paper and crayons to draw and color. We worked to keep their thoughts away from the possibility of death staring them in the face. As the bombardment continued, the children’s mental health became more important to me.

As a German certified trauma and emergency educator and counselor, I knew exactly what the situation demanded. Our dance school became a refuge for the children. They arrived, eager to use our special handshake and start dancing. While I felt afraid, I smiled to give them hope. Every day, we worked on step dancing for about 30 minutes. We also organized food and water for the children.

From 2014 to 2023, Gazan children needed a safe place

It wasn’t the first time we converted our dance school into a shelter. In 2014, we met 13-year-old Odey. With his parents enduring a worsening economic situation, he helped by machine grinding pepper at the local market. When asked how he was doing, Odey told me he was doing “nicely.” We ran into him often and, like the other children, we helped him with clothes and shoes. He heard about our dance group and showed up one Friday to see our weekly class and dance battle.

Eventually, Odey joined our dance group G1 or Generation One. As we practiced with the group members in Gaza, Odey and the others became strong and capable. They soon took up teaching other children to dance. The kids we encountered often felt unsafe in Gaza and even at home. They received little to no attention from their parents, who worried incessantly about having to relocate, having enough food and water, and stockpiling survival items. The children came around more and more as they sought safety and assurance.

Fast forward to 2023 and we saw a similar scenario. We used the UNRWA school at the Nuseirat refugee camp for dance, but as displaced Gazans began sheltering there, we felt unsafe. It also felt unsafe to dance in the streets, so we took it to the backyard. Because we often posted our activities on social media, we started to worry about becoming a target. When the children heard planes overhead during practice, they became terrified and stopped dancing.

The death of Walid: dancer and his family killed in bombing

It became increasingly difficult to encourage the children to drown out their fear and keep dancing. Two times, during dance class, buildings around us were struck by bombardments. The children scampered, running to us for cover. We hugged them tightly. After that, we temporarily cancelled our activities.

I’ll never forget sitting in front of the door and 50 meters away, a big explosion went off. Pieces of the building flew so high in the air; the gravity shocked us. I froze for three days, and I still feel it in my body but lack the words to express it. Some of our dancers moved to safer zones with their families, and we continued to teach the ones who remained.

In time, we all became used to the sounds of war. We stopped scampering. I saw the children as the present and future of my country and wanted, more than anything, to give them my best. Trapped in Gaza, thoughts of our little dancers often disturbed me. I worried about the ones who left the camp: were they still alive? One day, Azzam called me, and his voice broke. Walid, one of our young dancers had been killed along with his entire family.

As they sheltered in a home, a bomb wiped them out. My heart sank. When they found the bodies, Walid was wrapped in his mother’s embrace while his father held tightly to Walid’s brother. I thought of the boys, who I last saw in October. They came to class early carrying their water bottles and looking clean, with polished shoes. Smart boys, they behaved well and focused on their studies. I tried to process my pain and anger – to mourn them properly – but soon another family, friend, or acquaintance was killed.

Man desperately attempts to leave Gaza

Through it all, we focused on helping the children of Gaza cope. At each day’s end, we assessed their needs and provided what we could. Sometimes, we went to a church nearby to get water, charge our devices, and connect to the internet. Not matter how long we took, we always returned to children waiting for us.

Initially, Azzam was to leave on October 15, 2023. I was scheduled to leave on November 5. Despite having German and Egyptian passports, you needed to have your name on a list. The Israeli government decided whose name made it, and ours did not. Azzam constantly went back and forth to seek our authorization to go home, but soon, they cancelled the lists completely.

Once, Azzam travelled to the Egyptian border but when he arrived, the area got bombed by Israeli forces. He quickly ran back to his uncle’s house, but found no safety. Many houses around him lay in ruin. He captured one terrifying moment on Instagram. When I tried to contact him, the lack of internet and electricity prevented me. I left my location to find him but even obtaining transportation proved difficult.

Azzam and I tried repeatedly to get a permit to leave, but came up empty handed. Helpless and hopeless, we took our campaign online. Friends, family, and acquaintances around the world shared our story. Still, nothing worked. As we waited for good news, we continued to give our best to the children. Every day in Gaza felt like our last.

The children of Gaza deserve safety

Finally, after 75 days, news arrived that I could leave. While I felt good, thoughts of leaving people behind, including Azzam, haunted me. I worked hard to prepare the children, explaining that I lived in another country. I said, “I must go but I will be back.” Spending as much time with them as I could, I assured them I would help from my home in Germany. After a total of 83 days in Gaza, Azzam made it out as well.

As a trauma counselor, I know what I saw in the eyes of those children. I saw pain, dehydration, and kids who, against all odds, smiled and made us smile too. In their own way, they cheered us on. For about 20 days, I lost contact with the kids and my mind became consumed with thoughts of Gaza. Then, in Germany, I got news our studio was bombed.

I also received news that more of our dancers died. Rania, Totah, Maryam, and Dana – the next generation B-girl dancers – perished in the bombing that destroyed the Nusairat refugee camp. The news tore my heart apart. Rania had a best friend Habiba. Now, Habiba tries to cope with the death of her friend – struggling to realize Rania is gone forever.

This must stop. These children grow tired of going to sleep wondering if they will even wake up. They want their lives back – to return to school, socialize, and make friends. I want to return to Gaza and to the children when it’s safe. The roles of people like Azzam and I become critical in community building. I am a Palestinian and I want to return to Palestine. Our community needs us more than any other community in this world.