One of India’s human scavengers describes deplorable conditions

I see human waste floating like dead fish around me. A skin-crawling mix of insects, drain flies, and spiders stick to the pipes and walls and swarm around me.

I risk my life with each breath.

- 4 years ago

November 3, 2021

GHAZIABAD, INDIA—I immerse myself in human and animal excrement every day to provide for my family. It is an unimaginable nightmare for most, but this has been my reality for the past two years.

Desperation leads to a last resort

Two years ago, I was looking for an honest way to earn money. Since I belonged to the Dalit Caste, everyone hiring for a decent opportunity turned me away.

Dejected, I applied to be a sanitation worker for my local municipal district. It is the most dehumanizing profession, but I didn’t have any other options. I did not have the education, affluence, or the “right” caste to pursue anything else.

My family opposed my decision, but the pressure to get employed and the assurance of a permanent government job overrode their concerns.

To my horror, my employer hired me as a private contract worker instead of a government employee, with a salary of just 10,000 INR ($134 USD) a month.

On paper, I was to assist in cleaning the sewers mechanically. But in reality, I had unwittingly become a manual scavenger, physically entering sewers, manholes, and septic tanks and cleaning the waste by hand.

My days are a living hell

The first thing many people around the world do in the morning is pray. I start my day by entering hell itself.

I can barely bring myself to describe what I see, smell, and feel inside the sewers and manholes.

During my work day, I spend at least two hours inside a dark, filthy sewer with no safety equipment or protective gear. I unclog the public drains of human and animal waste, all while wearing my clothes from home.

I see human waste floating like dead fish around me. A skin-crawling mix of insects, drain flies, and spiders stick to the pipes and walls and swarm around me.

Everything smells burnt. The cocktail of gases circulating in the sewer is toxic and potentially lethal—I risk my life with each breath. I often suffocate and lose consciousness, but I survive.

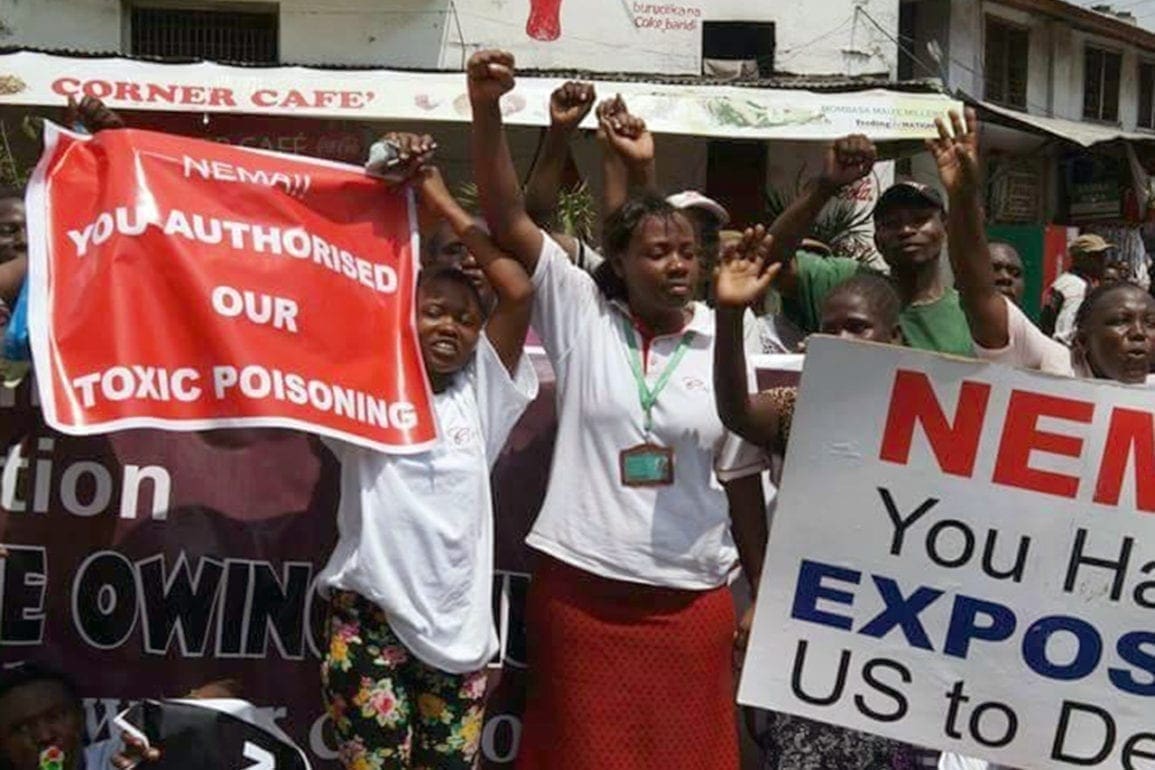

Many of my fellow scavengers have choked to death due to asphyxiation or drowning on the job—they couldn’t sense the poisonous gases that lurked. Some lost their lives trying to help their trapped mates. Not all families who lost their breadwinner received compensation.

Since becoming a scavenger, illnesses and injuries plague me. From headaches, fatigue, gastroenteritis, skin burns, and cuts to respiratory tract infections, I have suffered tremendously.

The stigma of scavenging

I take a bath twice a day, but no one wants to touch me. The smell just doesn’t go away.

I entered into this profession because I had no choice. Life has stranded me here. Given a chance, I would quit. But who will give me that chance? Who will employ me?

The Supreme Court of India spoke out about the plight of people like me in 2019, saying manual scavengers are like people sent to gas chambers to die. The Indian government promotes movements like Swachh Bharat Abhiyan, which pledges to eliminate open defecation and improve solid waste management.

None of it has made a difference. I feel the government doesn’t actually count someone of my low status as a person, so why would they notice my despair? Or, perhaps, because it is the worst job in the world, neither the politicians nor the upper caste activists care to liberate us.

I have been deprived of my fundamental human rights. The disgust of everyone around me overwhelms me wherever I go. My life feels undignified and meaningless.

I am risking my life and health every day. But I feel helpless. The most undesirable, high-risk job is the only one in my country that allows me to bring food to the table, so I do it.

I die every day, but at least my family is living.