Father’s death leads son to advocate for firefighter cancer awareness

When my dad died, the burden of proof was on the individual; it didn’t matter that four firefighters all died off the same thing at the same time. My mom was raising four kids and didn’t have the means or ability to fight the city. “He got cancer,” I always thought, “just like the city said.”

- 3 years ago

December 29, 2021

COLORADO SPRINGS, Colorado—I walked from my hotel, down the streets of Colorado Springs, toward the Fallen Fire Fighter Memorial.

The late September weather marked the start of autumn, and the sprawling blue skies exploded with big puffy, white clouds. It was a perfect day.

I paused at the front of the memorial where it faces the street. Surrounded by green lawns, with the mountains as a backdrop in the distance, the large black granite walls stood tall. Over a dozen panels protruded from the ground, encircling a grand sculpture of a ladder, unsupported at the top.

A fire fighter climbed down, carrying someone they had rescued. He seemed to be emerging from the heavens.

A unique visit to remember my dad

I had been to the memorial before, but this time a solemn beauty overtook me. I noticed everything: the International Association of Fire Fighters’ logo, the Maltese cross, and the people standing in front of the names on the wall.

In past years, I attended the annual memorial service to honor members of our fire company who had died in the line of duty. At that event, a large crowd swallowed up the area around the memorial. Bag pipes sounded as pomp and circumstance ensued. This time, however, was different.

COVID forced organizers to cancel the event in 2020. A year later, in September 2021, it was just me, alone. I was there to visit with my father.

I made my way to the back of the memorial. Hundreds of names shone off the granite, organized by the year they were added. Personal notes, prayer cards, and flowers dotted the wall and surroundings, and in some places, a lip stick kiss caressed the name of a lost loved one.

Those names represented people who died tragically, their lives cut short in service to the community. It is an honorable thing, but each of those honored names is accompanied by a story, a family.

As I made my way around the circle of walls, I took pictures of the names of fallen firefighters from my local station.

I could see my dad’s name from a distance, but I waited for a group already gathered in the same area, mourning their own lost loved one. I didn’t want to crowd them in their grief. When it was my turn, I approached the wall. Etched there, it said, “Harry Lee Frazier.”

My father’s name had been added to the wall in 2020, but he died in 1982. It took 38 years for his death to be recognized as one caused by occupational cancer, a result of his time as a firefighter.

Searching for memories of my father

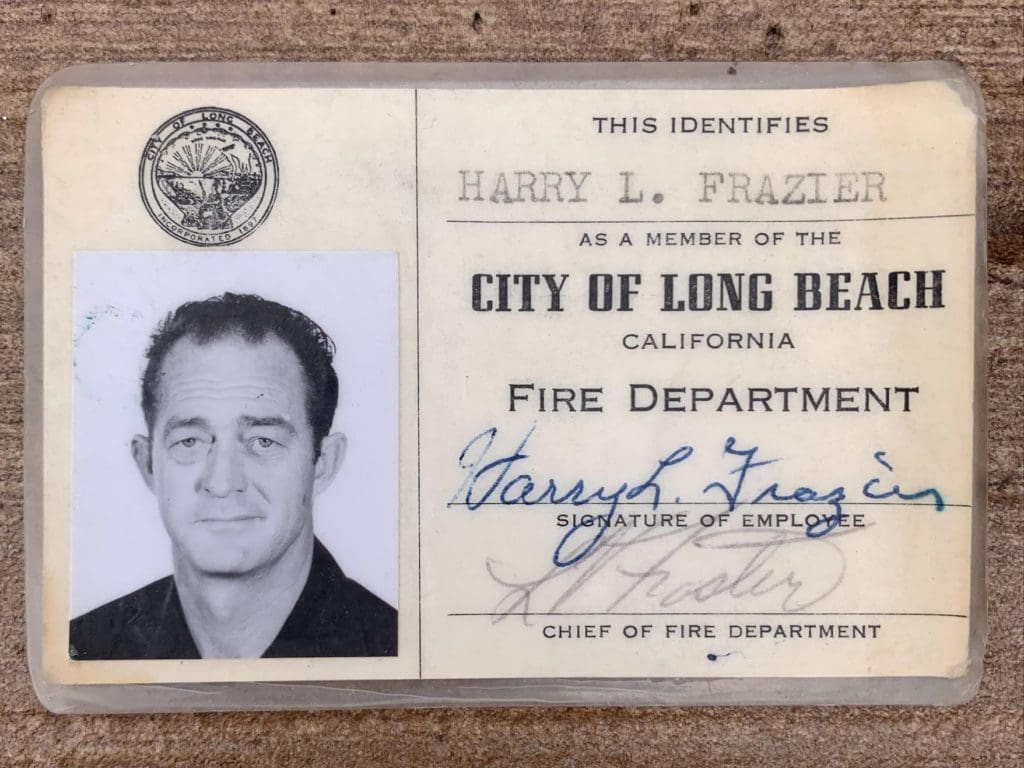

I was finishing high school when my dad died in 1982. He was a firefighter in Long Beach, California. He passed away long before I became a fireman myself, at just 58 years old.

Dad was my hero growing up. For years after he passed, I tried to piece the memories together. The story I recall was that dad, and three other firefighters from the same company, were diagnosed with brain cancer at the same time.

Presumptive legislation (laws that say cancer deaths in firefighters can be presumed the result of their work) only came into existence in California in 2000. When my dad died, the burden of proof was on the individual; it didn’t matter that four firefighters all died off the same thing at the same time. My mom was raising four kids and didn’t have the means or ability to fight the city. “He got cancer,” I always thought, “just like the city said.”

My own career as a fire fighter started in 1985 after college. Even then, our logbooks were all handwritten. There was no exposure reporting and no method of tracking incidents of exposure to cancer-causing toxins, and we had no background on cancer amongst our ranks. For three decades, I worked and didn’t give it a thought.

I always felt, and still feel, hungry to know more about my father. Spending my entire adult life in a fire station, I wonder what he was like there.

I know he was a captain, promoted through the ranks quickly. We lived in the city where he served so he would often show up at the house to see us or we would visit him at the station. Going there as a kid, I felt incredible. When I walk into the apparatus room today, the smell takes me right back to childhood. I remember standing in that space as a little boy.

When my father died, I was a teenager, growing up and trying to learn who I was. Now, I often wonder, who was he?

Connecting the dots between firefighting and my father’s death from cancer

Three decades into my 35-year career, something happened that changed everything.

I was attending the National Fire Academy in Emmitsburg, Maryland, a sprawling, fenced-in campus featuring a cluster of historical brick buildings.

As I sat in a room filled with fellow firefighters, the speaker used a phrase I’d never heard before. He talked about the “firefighter cancer epidemic.” Instinctively, my brain challenged the words. Is it really an epidemic, or are they using the word because its fantastical?

I began to research and in no time, a story unfolded before me of firefighters getting sick and dying from cancer at astronomical rates.

The gravity of the Fire Fighters Memorial Wall suddenly seemed more serious. In the 2020 ceremony that was cancelled due to COVID, they were going to add 265 names to the wall; 211, or 80%, were cancer deaths.

I began to realize a terrible fact: my dad died from the job.

A new mission, guided my father’s legacy

Being a firefighter is not just about sitting on the fire engine, waving at kids, and hanging out with the guys at the station. Questions about my father’s death laid dormant in me for 30 years. When I heard those words—cancer epidemic—it triggered a purpose that has driven me to national involvement in firefighter cancer prevention efforts and research.

Now, as an educator, when I stand in front of a room of 100 people, I ask, “How many people here have had a family member with cancer?” I see a smattering of hands. Then I ask, “How many of you have had a brother or sister firefighter who fought or died of cancer?” Nearly every hand goes up.

“This is the family history you need to consider,” I say.

Sixty-four percent of fire fighters are going to get cancer at some point in their lives. My work is about growing awareness and prompting action.

We will never be able to say there are no hazards on the job. We cannot package firefighters up in bubble wrap when we send them out on the truck, but we can motivate people to make small changes that can make a difference, like rinsing off immediately after a call before laying down to sleep or regularly sending your gear out to be professionally cleaned.

There are two things firefighters hate: the way things are done and the thought of change. It is a tough transition, but I know we can do it.

In 2020, the Long Beach Local recognized my dad as a line of duty death with the International Association of Firefighters. I had the opportunity to see his name etched into the wall in 2021.

Firefighters are perishing in their communities from this epidemic every day. We can do more to prevent families from suffering like mine did. Today, this is my passion and my purpose.