I am a Rohingya refugee in India, not a terrorist

I was a refugee, a slave in my own country. I came to India to escape decades of statelessness, violence, ethnic cleansing, and genocide. Now, I am called an illegal immigrant.

- 5 years ago

August 28, 2021

NEW DELHI, India — People do not become refugees by choice. Circumstances dictate our status.

In my original home of Myanmar, the Rohingya people had no citizenship rights. We could not move freely, obtain higher education or government employment, and we could not vote.

The military destroyed our mosques, banned our religious gatherings, confiscated our land and farm animals, raped our women, and pushed us into forced labor.

We had to flee.

My people fled ethnic cleansing and became refugees in India

In Myanmar, my people were kidnapped, tortured, and executed if we didn’t abide by the government’s rules.

My father was a businessman. One day, he was abducted from our home and tortured in prison for two months. He was beaten with sticks and rods, punched and kicked during interrogations, and burned on his legs with candles and cigarettes.

Throughout his arbitrary detention, he was served food even dogs would not eat. He was deprived of drinking water for days and the sanitation was abysmal.

To escape decades of statelessness, violence, ethnic cleansing, and genocide, my people and I crossed the Bangladesh border and came to India.

The journey was perilous. Most of my fellow Rohingya’s died of thirst and starvation through the mountainous terrain. As illegals entering India, the locals took advantage of us. Many of my people were lured with the promise of jobs then looted and left to die.

My family traveled for hours on foot. We feared losing our lives; being killed by India’s Border Security Force and forcefully returned to hell.

We were hopeless, terrorized, and hurt.

Rohingya refugees face unsafe work and housing conditions

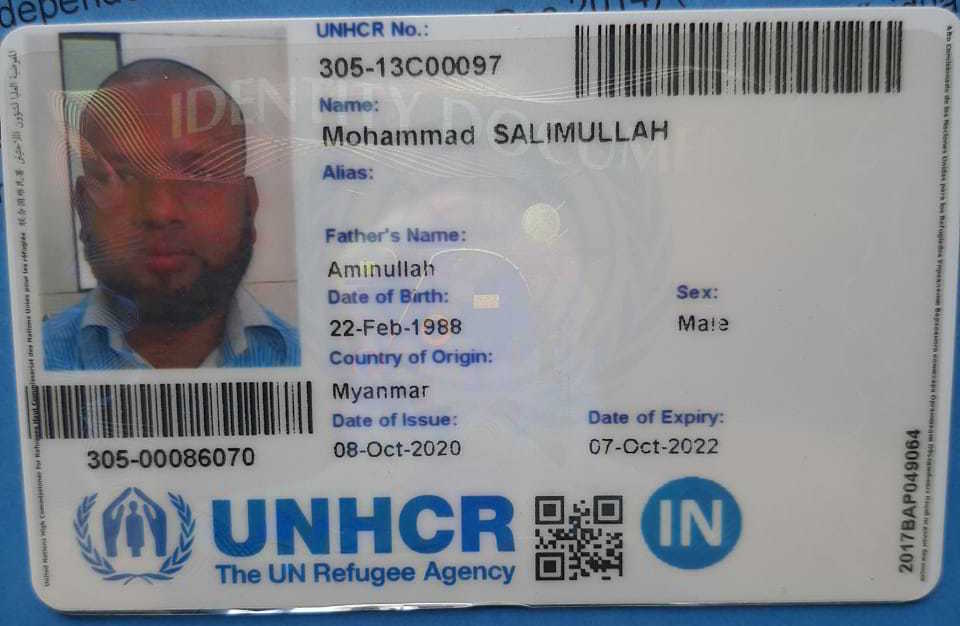

Despite being labeled refugees by the United Nations High Commission on Refugees, the Indian government considers us illegal immigrants with no rights.

My people are often exposed to exploitation with no access to social safety nets.

UNHCR’s Refugee Cards are not accepted as valid identification for work. Without Visas and Aadhaar Cards, we struggle to find reliable and safe employment.

We are forced to take on precarious work in informal sectors of the economy with few safety standards. The only option is day labor and low-skilled, insecure, highly exploitative work.

We regularly face unsafe conditions, low pay, withholding of payment by employers, and limited opportunity. During the COVID-l9 pandemic, Rohingya families were at heightened risk of hunger, illness, and violence.

I lost my wife at that time. She could not get the treatment a citizen or refugee deserves in India. While her test reports came back negative for COVID-19, she was experiencing breathlessness so the doctor’s wouldn’t touch her.

When her condition deteriorated, she was kept in a COVID ward. After three days, the doctors notified me she was dead. If I were an Indian, she would have been transferred to the Intensive Care Unit.

After a lot of commotion, they gave me her body and to my horror, it was disfigured. There were marks on her stomach like she was operated upon. I believe they sold her organs. There is no proof she died of COVID.

Living in destitute conditions with no prospects

Housing and living arrangements have become increasingly insecure for us. We live in tents on the outskirts of cities. Flooding and fires often destroy our shelters. We continue to live in baking hot, temporary tents without the prospect of resettling elsewhere.

India is home to refugees from at least 15 countries. Many refugees are treated well, but not the Rohingya people. Without a Visa or passport, we cannot leave, yet India calls us intruders.

Since 2012, I have worked as a laborer, housemaid, and a helper in shops. How am I a threat to India’s security? I do not have a country to call my own. I can neither go to Myanmar nor stay here. My people deserve fundamental human rights.

The government and ministers say we are a threat to India’s security and indulge in illegal activities, but they do not send us to jail. Right-wing Hindutva outfits say we are terrorists, yet we are allowed to live in roadside camps.

I live in an 8’ x10’ tent with my two children. We have no toilet, drinking water, or water to cook and bathe. Humans should not live like this.

Dreams of a better life destroyed in a fire

Every few weeks, we are asked to move. This robs us of the prospect of a better life and leaves us unsafe and vulnerable.

If I could just go back to my country, why would I be living like this? I would not choose to live with my children in illegal slums, but it is the only option we have.

At one time, I had worked enough to open a small grocery store, but it was destroyed in a fire, and I am unemployed once again. Due to the pandemic, I cannot find work. I am surviving on donations.

Opening another shop makes little sense when our temporary settlements are regularly destroyed, and we are displaced again. Whether I am happy or sad, this is my life.

If I could, I would go back home; back to my land. If the Myanmar government had not killed and tortured us, I would not have left in the first place.

Despite horrific conditions, India is still safer

In India, we can live, breathe, educate our children, and use medical facilities. Back in Myanmar, we were denied access to education, healthcare, opportunities to earn a livelihood, and basic services.

In this way, India is safer. We do not need anyone’s mercy. The Rohingya people are not here to stay forever, but we do have a right to live with dignity as long as we are alive.

Non-Muslim minority communities from Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Bangladesh are awarded citizenship in India. Yet, the Rohingya people, who are Muslims, are persecuted.

We have nowhere left to go.