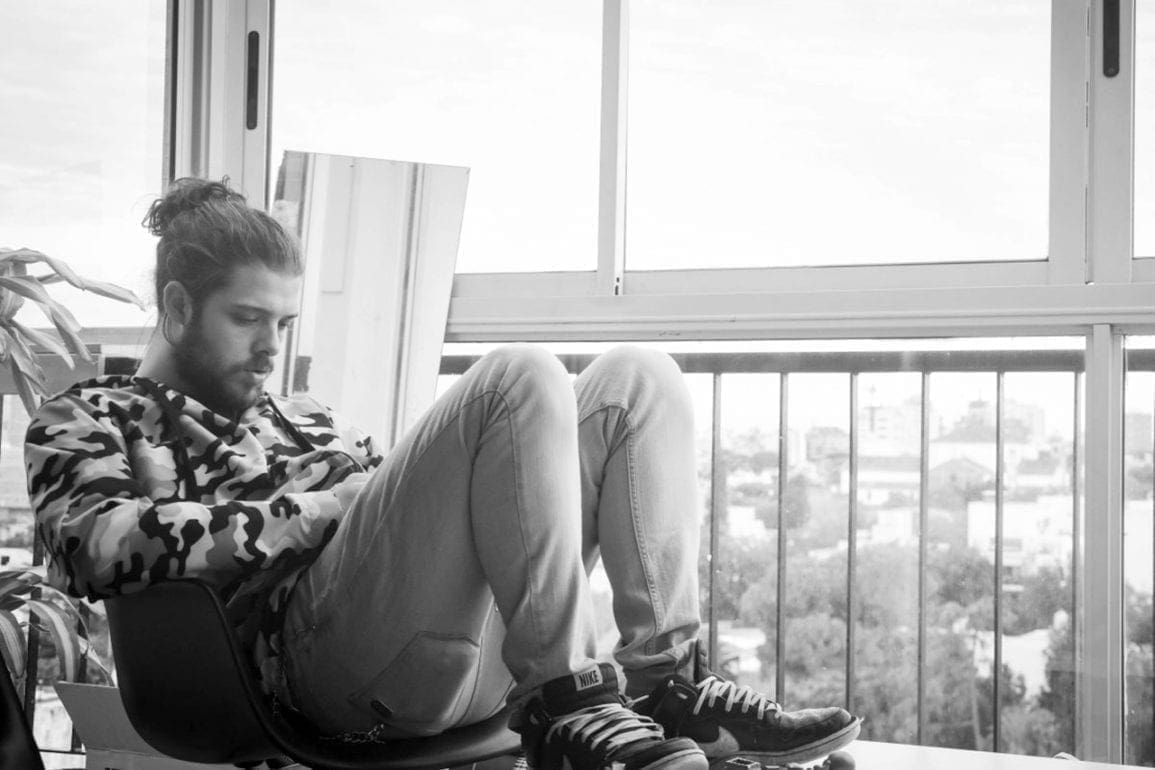

For Argentinian record holder, competitive athletics is just another job

For me, athletics aren’t an emotional experience. I don’t keep my trophies or medals or study running history; I’m not one to watch races or read too much about it. I run to support my family—that has always been my goal.

- 4 years ago

March 4, 2022

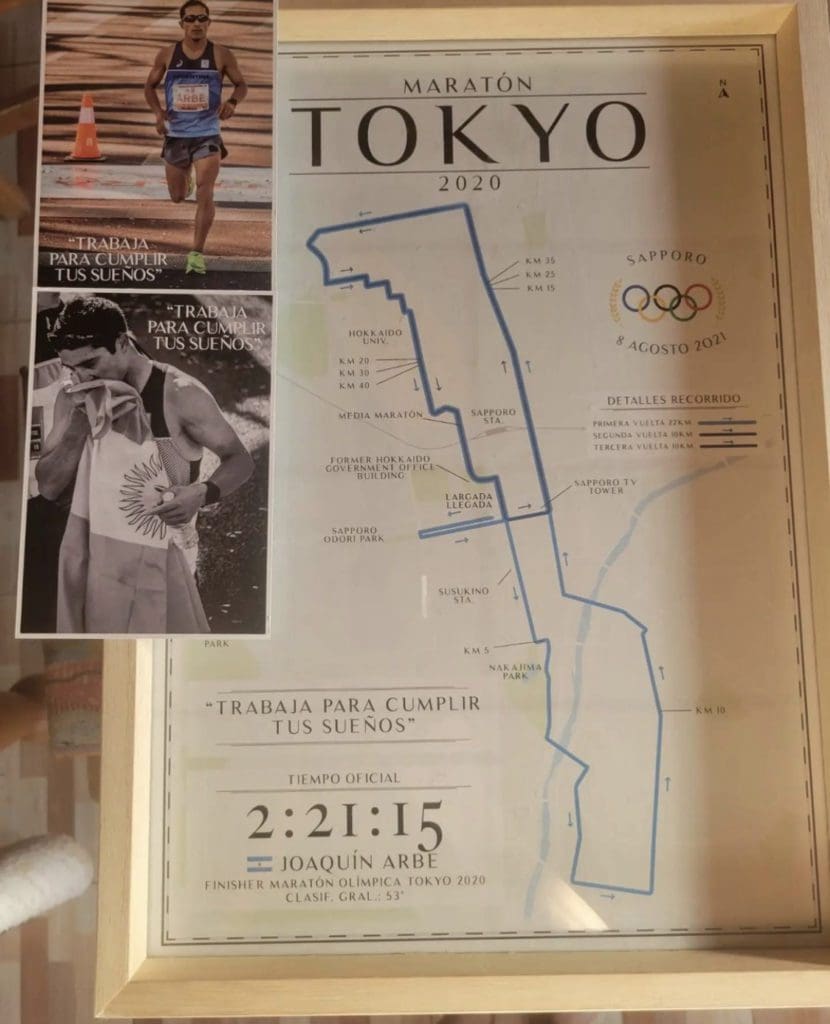

ESQUEL, Argentina—I earned the marathon record time for my country and have won 45 national championships in different competitive running disciplines. But they didn’t generate anything special for me, because I didn’t get anything in return. In Spain, Brazil, the United States, or Japan, for example, they pay those who break national records; in Argentina, we get nothing.

For me, athletics aren’t an emotional experience. I don’t keep my trophies or medals or study running history; I’m not one to watch races or read too much about it.

I run to support my family—that has always been my goal. If athletics didn’t give me the money to cover the expenses of my wife and three children, I wouldn’t do it competitively. I would rather get another job and securely provide for my family.

Recently, competing has allowed me to grow: I have my own house that I was able to expand; I bought a car; and I’ve been able to travel all around the world. For now, I’m doing well, and what I earn is enough for me.

However, when my running career didn’t provide enough, I worked as a bricklayer. First, I worked together with my grandfather Toro, who taught me the trade, then alone.

Balancing a talent for running with making a living

I started practicing running at age 12. Some friends invited me along when they went to train at a track one evening, and I went. When I joined in, I realized that this felt good, and I started to like it.

I looked at training as a game, as something fun. I liked to go, run and hopefully win. As an extremely competitive person, I always want to win—and most of the time, I do.

Starting around age 16 for about a decade, I worked with my grandfather as a mason. I trained for my athletics at 7 a.m., then worked from 9 a.m.-5p.m. in construction. Then at 7 in the evening, I would train again.

I got used to adjusting the workouts according to my job demands. I also got used to training on my own: if I spent eight or nine hours pouring concrete, lifting bags of cement, or fixing a sidewalk, I couldn’t follow a conventional training plan like many of my peers.

When I got a scholarship from my province, Chubut, in 2016, I stopped working daily on the construction site. For a while, I took some jobs that I knew would take me a week, on average, so as not to modify my workouts too much.

It was only when I got the mark to qualify for the Tokyo Olympics that I left construction completely, or almost; I continue working to expand and fix up my house, but I no longer work for others.

Not your average athlete

Due to my unique habits, I manage my own training sessions. Because I work so differently than other athletes, I don’t have a coach to avoid the inevitable conflict.

Sometimes friends invite me to play soccer or run a bike race, and I accept. Other athletes wouldn’t do it because of the risk of injury, but nothing has happened to me yet, so I’m going to keep doing it. Although I have the ultimate goal of running the marathon in the 2024 Paris Olympics, this year I wanted to run the 3,000-meter hurdles. They told me it doesn’t suit me, but I’m going to do it anyway. I want to get a national record in that as well.

If I go to bed at four, five in the morning, I know that the next day I get up and I have to train all the same. But I’ll still go to bed late.

With nutrition, I’m also kind of disastrous in terms of eating like a serious athlete. I’ve never had a nutritionist—I like getting together with my friends, eating barbecue and having one or two beers. I try to eat half healthy in competition season, and I don’t eat fried, but that’s about it; it just doesn’t have much importance to me.

Once, a nutritionist told me I should eat thinks like half an avocado, half a tomato, and a chicken breast. But I have my three children and my wife, too; what are they going to eat? If I had to make that meal for everyone, I would spend the money I usually spend to eat for three days in one meal. I eat what I have and what I can.

Planning for the future

This year I am going to dedicate myself to track; especially to the hurdles. I also want to compete in a marathon in the United States. Starting next year, I’m going to look for the mark to qualify for the Olympics in 2024.

When I retire, I will be a coach. Now I am in charge of a little athletics school, where my daughter trains. She is doing well and wins many races. Like me, she doesn’t keep her trophies or medals. She gives them to her grandparents, aunt, or godmother.

I am her father when we are at home, but when we train she has to pay attention and follow my instructions comply like everyone else. I take competing seriously, and I expect the same from the kids. I tell them that if they want to stand out or win something, they have to push themselves. If it’s just a recreational pursuit for them, I pass their coaching on to another teacher.

I never considered athletics as entertainment or as a dream. However, since I started earning money with races, I do consider it a career like any other.