Indian engineer turns dirty, dying lakes into pristine ecosystems, sets sights on cities around the world

I brought in plants known to purify water as a sort of natural sewage and released native fish species known to help with water clean-up. Planting jumbo grass, bamboo, and umbrella grass prevented pollutants like bottles, plastic, thermocol, and waste material from entering and retaining muck.

- 2 years ago

July 26, 2024

BANGALORE, Karnataka ꟷ When a newspaper article emerged in 2016 predicting that Bangalore, like Cape Town, would become a “zero-water” city by 2025, I lost sleep. [Once known as the “City of Lakes,” Bangalore boasted over 1,000 bodies of water. Zero Day is the “day when the municipal water supply for this major city was estimated to run out.”]

The report said that by 2030, more than 25 more cities may face a serious water crisis. As a mechanical engineer, I began studying the fundamental causes and carrying out research on the subject. Data I obtained revealed a stark reality: many of Bangalore’s lakes already went dry and the Karnataka government discontinued rejuvenating them. One thousand lakes, once brimming, dwindled to about 400.

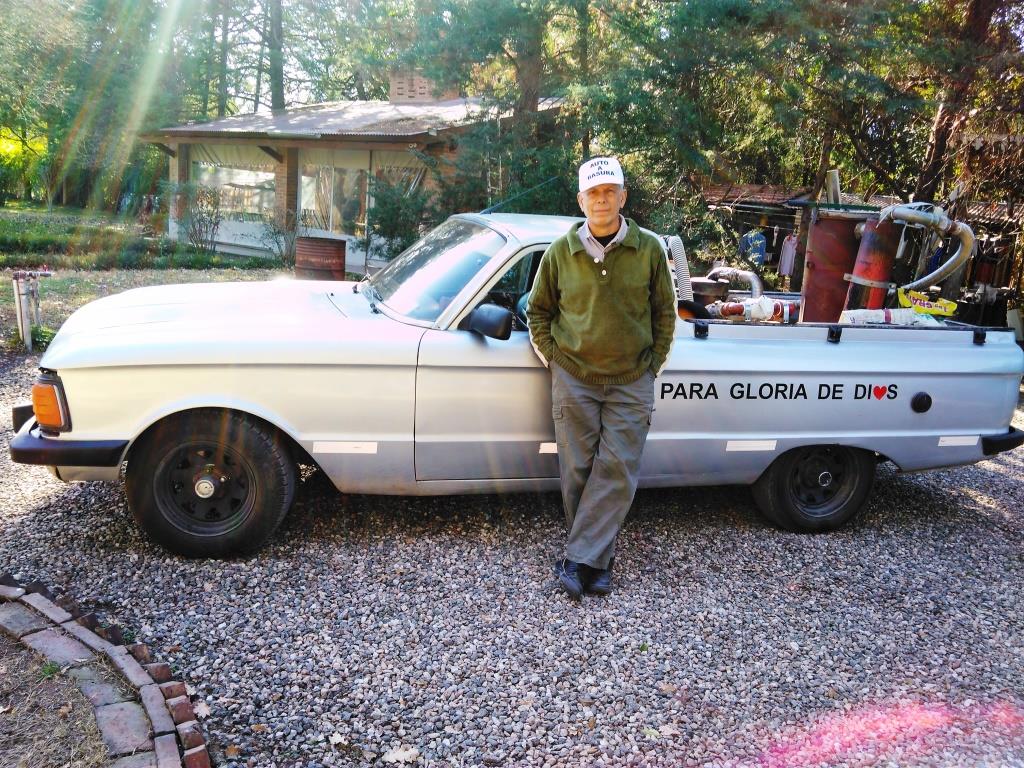

Since 1990, as Bangalore transformed into a concrete jungle, the government and what we refer to as the land mafia and builders, buried many lakes. About 15 to 20 percent of all remaining lakes experience encroachment and the area cannot be cleared. Rainwater that once flowed to the lakes began moving in different directions, the lakes dried up, silt accumulated, and the high drain walls became submerged. The more I took action to save these previous resources, the people of my country began calling me “India’s Lake Man.”

Read more water stories at Orato World Media

The government’s failure to improve water quality affected farming activities

I saw firsthand how lakes in Bangalore transformed into septic tanks. The muddy water continued to flow, carrying chemicals, sludge, detergent and industrial effluents. It eventually reached four rivers: Pinakini, Kumudvathi, Vrishabhavati and Arkavathi. These rivers become fully functional waste canals as they flowed towards the perimeter of the city.

Thousands of farmers who relied on this water for farming became unable to produce crops. The government also failed to provide experts to handle both black and grey water. In addition, political pressure and corruption played a part in many lakes being either stinky with algae or covered in hyacinth.

I did not see the government attempting to improve the water quality or the ecosystem of the lakes. Rather, it invested two to three billion rupees annually on beautification. It is estimated that 25 lakes have been enhanced throughout the years. Unfortunately, none of them are suitable for swimming, let alone drinking.

When I took the helm of the Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) team at the Sansera Foundation my life took a dramatic turn. The foundation concentrates on lake recovery, so my employer paid me nine and a half million rupees to rejuvenate a lake. The 36-acre Kyalasanahalli Lake in Bangalore near Anekal became my first project. It remained dry for the last 40 years, but I brought life back to the lake in just 45 days.

I encouraged locals to assist in rebuilding the devastated area and asked for their blessings. The women became my main source of support. I excavated 1.40 lakh cubic meters of soil, which I used to construct a walking path that borders the lake, effectively acting as a wall to keep out undesirable water and biomass. In addition, I planted 18,000 seedlings of various fruits, flowers, vegetables, medicinal plants, etc.

My work cost lower than previous contractors had taken from the government

After nine to ten days, the lake filled with rainwater. By then, I felt fed up with the politicians, drunkards, builders, industrialists, and grazing men who tried to chase me out. I had enough. Then, one day, I went boating on that very lake and discovered the water level went up over six feet.

The bore-well began slowly filling again and small-scale farmers resumed cultivating vegetables. I received their first crop and saw their happiness at the possibility of leaving their new jobs driving rickshaws behind. Inspired by this achievement, I began to resurrect additional lakes and between 2018 and 2019, restored four lakes including Vabasandra.

Some environmentalists, who had ties to the government and did little to enhance lakes, chastised me for finishing the project in 45 days. They called me a techie, not an expert. In fact, they said I ruined the lakes using unconventional, non-scientific, non-technical methods. They argued about how I succeeded with barely 9.5 million rupees when the standard cost for lake revival according to the government is between five and ten million per acre.

Soon after, the foundation switched things up and moved me to another group. Having developed a passion for the lakes, in 2019, I left my job to start the nonprofit Malligavad Foundation. To date, my organization restored more than 100 lakes nationwide to their former glory, including 35 in Bangalore. The 756-acre lake that surrounds Bangalore is the largest lake I am working on at the moment. My medium-sized lake is 170 acres, and my smallest is 3.5 acres. It warms my heart to see birds and fish making the lakes home.

India’s Lake Man sets goal for country to have excess drinking water by 2030

I face the most difficult challenges securing the go-ahead from authorities and removing encroachments. India’s population includes 1.4 billion people, yet something like 10 percent have the authority to alter the earth. I cannot rely on companies, governments, or specialists, so I focus on a people-led movement; on transformation instead of simple activism. I engage the people in the process.

At the same time, it takes significant time and money to rejuvenate lakes and maintain them. I began to wonder, “Why can’t I make this less expensive, less time consuming, and naturally self-sustaining without maintenance?” When I traveled to Karnataka to visit nearly 200 lakes, I made a stark discovery. During the Cholas dynasty, they constructed Sixteenth Century lakes, dams and canals without any financial support, engineers, or architects. I became inspired.

Soon, I began talking to the elderly farmers. They told me stories of trees being chopped down to make way for urban expansion. Those engaging in deforestation did so ignorant to the role of the tree as the earth’s water tanker. Each tree serves as a 5,000-liter reservoir, harvesting rainwater and recharging the environment.

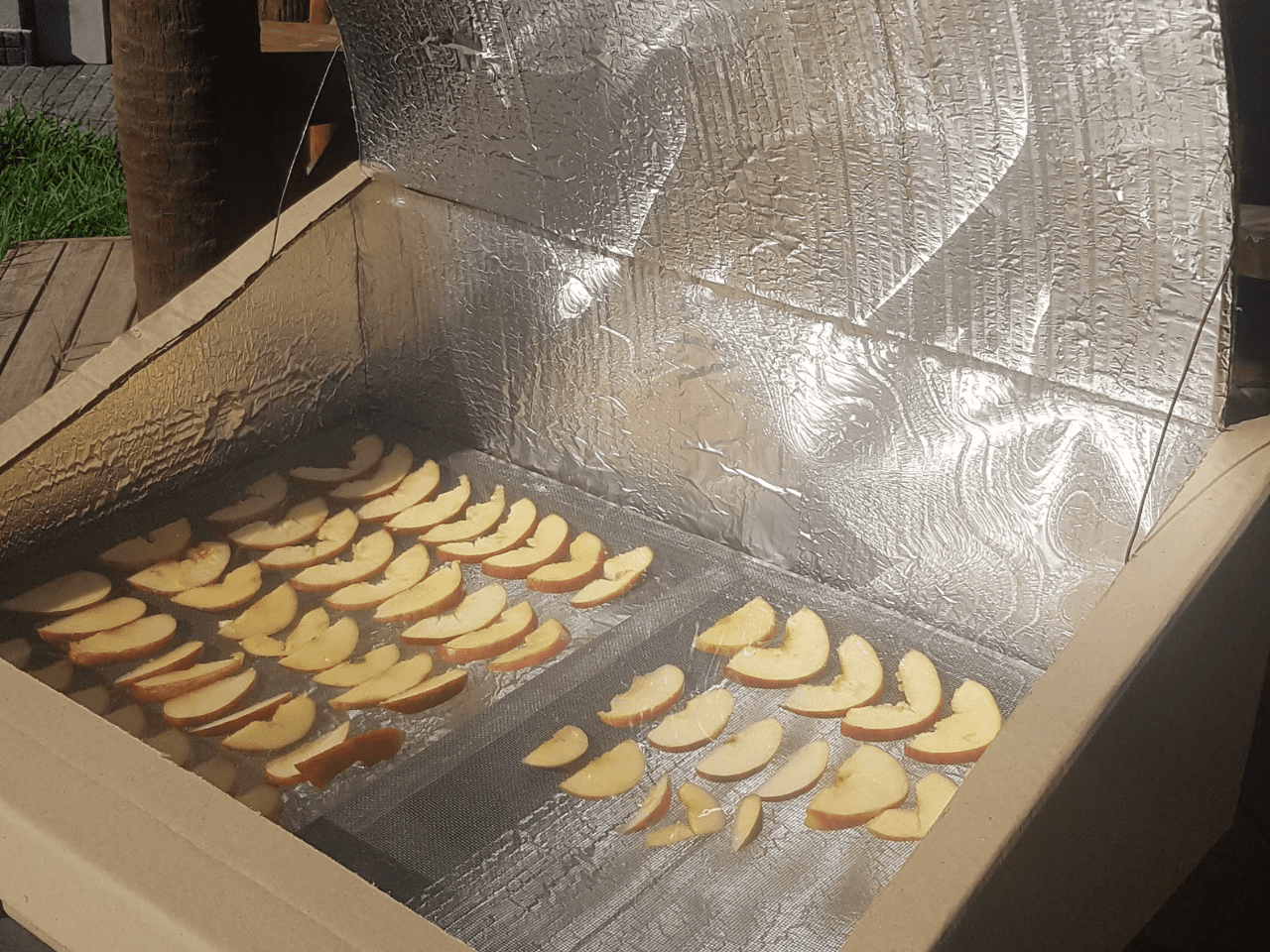

With all of this in mind, to obtain water, I began excavating the ground and building a boundary using the excavated soil. I brought in plants known to purify water as a sort of natural sewage and released native fish species known to help with water clean-up. Planting jumbo grass, bamboo, and umbrella grass prevented pollutants like bottles, plastic, thermocol, and waste material from entering and retaining muck.

We never rely on electrical equipment, STP (Sewage Treatment Plant), or ETP (Effluent Treatment Plant) technologies. Using hydroponics and sunlight, we effectively destroyed bacteria, reducing stench. These natural mechanisms helped us purify 70 percent of the water.

Facing persecution and death threats while rejuvinating India’s lakes

Lakes serves as the lungs of the earth, cleansing contaminated water, and my work gained momentum as we rejuvenated more and more lakes. The central government began adopting my methods and some corporations offered financial assistance. The government also designated me as an advisor for a 12-lake restoration project. I even took on a project in Africa to revitalize 10 lakes and a fish factory, and in Ibadan, Nigeria called me to tackle their water problem.

Nevertheless, I face some persecution. Certain individuals filed lawsuits and I face 17 cases. I never imagined being drawn into disputes doing good for the people. During one project, we opened the first day organizing a land worship. Soon, certain individuals advised me to postpone the lake rejuvenation for two days, and I followed instructions.

When the work did begin, people rebelled against me in what felt like a purposeful plan. I possessed the needed paperwork and lake map, so I carried on. One day, an encroacher threatened me with a sword, shouting, “Let the government do it; who are you to do it?” He threatened to hack me to pieces. I stood firm, telling the man I had nothing to personally gain from the project.

At another site where industrial influences remained present, they stayed on my back day in and day out. I went to the local authorities for protection. Halfway through construction, politicians instigated the locals to protest. They accused me of taking the land for myself. While working on my seventeenth lake, a group of 40 people surrounded me, threatening murder. I explained that the lake remained public, and the work benefited the locals personally. They left me alone.

From India around the world, man seeks to create model lakes

This critical work resulted in clearing encroachments on 92 acres of government land. Rather than handing over responsibility for maintenance, I continue to serve. I fear the government would ruin them. Ecological restoration of clean water in its natural environment also reduces the government expenditures for beautification.

In these now stunning spaces, I come across joggers, walkers, and pet owners. I see older residents appear, keeping an eye on the lakes. During the first 10 restorations, we made some mistakes but learned from them and fixed those errors. All along the way, villagers, the elderly, and volunteers showed up to help.

Today, I have a supervisor and two gardeners working at each lake, and one engineer assigned for every five lakes. Fifty staff members and eight lake volunteers keep the organization going throughout India. I plan to turn these volunteers into Lake Men like me. Looking to the future, I seek to revitalize 185 lakes and 23 streams between 2027 and 2030, and to positively impact the Pinakini River. Looking further, I want to build a model lake in each of the 280 capital cities around the globe. Till my last breath, I shall keep regenerating lakes.