Sahara surprise

By afternoon, a fierce wind was driving fine, superheated sand through the air. The temperature was a broiling 120 Fahrenheit.

- 30 years ago

July 30, 1996

This story was originally published in 1996.

It was our sixth day of running in the Marathon des Sables.

We had to cover 76 kilometers (46 miles], the longest segment of the race. The fastest runners would be in camp by late afternoon or early evening. For the slower ones like me, it was going to be a tough day, night, and day in the desert.

By afternoon, a fierce wind was driving fine, superheated sand through the air. The temperature was a broiling 120 degrees Fahrenheit. My backpack full of food, clothing, emergency flares, and first aid supplies weighed heavy on my shoulders, which had ached ever since the second day. To keep from getting infected, I put several layers of medical tape across my back and added a couple of layers of foam rubber to the shoulder straps of my backpack. But as the day wore on, my blisters really started to hurt.

Walking over walnut- to fist-sized rocks was not conducive to well-being. I adjusted my gait, walking on the outside of my shoe soles, my heels, wherever it hurt the least.

As evening approached, I walked alone across the moon-like surface of an ancient lakebed: rocks, no vegetation, and dead silence. I finally reached one of the three mini-camps along the route by starlight at about 11 p.m. After dinner, I squeezed amongst three other runners on the cluttered floor of an open Berber tent. After five hours rest, I was off again.

The fourth stage ended up being a two-day stretch for me. I didn’t finish it until Day 7 at 5 p.m.

Sand storm

By day eight, I was walking gingerly to avoid hitting the most painful areas of my feet. I struggled over sharp rocks, loose stones, and uneven terrain, knowing that after today there would be only one more 18-kilometer trek of agony.

What was I doing in this sunburned hell at age 56, while the average adventurers were in their mid-40s? Simple! Age never seemed an obstacle for me, and after doing the Antarctic marathon the year before, this was just what I needed. I love a challenge, an exotic country, extreme events, and a hot desert.

In the early afternoon, I was alone, climbing one huge sand dune after another, when the sky darkened and a gale-force wind started to blow. A sandstorm was coming. I wrapped myself in a Mylar space blanket, tightly covering my entire body, including my head and backpack, and huddled on the ground. Still, the sand hit me like thousands of tiny needles. I was scared. What if I was buried by a mountain of sand and suffocated?

Suddenly it was quiet again. I peeled myself out of the Mylar mess. Sand fell into every crevasse of my clothing and body. I felt like I was wrapped in sandpaper. I took all my clothes off and shook the sand out.

However, I now had a much bigger problem — where in hell was I? The sand was everywhere; no yellow markers flagged the route and not a soul was in sight.

I had been stumbling through the dunes for 15 minutes when I saw an odd shape stretched out in the sand. What the hell could that be? I wasn’t sure I wanted to know. I brushed away the sand and a human body, face down, emerged. Another runner. I shook him a few times.

He didn’t respond. I thought he was dead so I wasn’t sure what to do. I smacked him around to try and wake him up. He moved a little and I could see a bit of his face. It was red like a lobster and blisters were starting to form. He whispered something I couldn’t understand.

I heard and saw enough to know he was near death and I had a big problem on my hands. I covered him with my space blanket to protect him somewhat from the scorching heat and left him the last of my water. I told him I had to go for help. I don’t know if he heard me, but I had to do something if I wanted to save what was left of him.

The mirage

After a quarter of an hour of walking, I saw two tiny figures in the distance. Squinting my sand-blown, raw eyes, I realized I had two rag-clad 10-to-12-year-old Bedouin boys here. Was it a miracle? I don’t normally believe in them. I don’t speak French, or Berber for that matter, so I took one of the boys by the hand and pulled him in the direction I had left the fallen runner. When we got there, they shook him. He gave an animal-like grunt. I hoped they knew what to do because I sure as hell didn’t. The boys tried to articulate their plan to me, then they left.

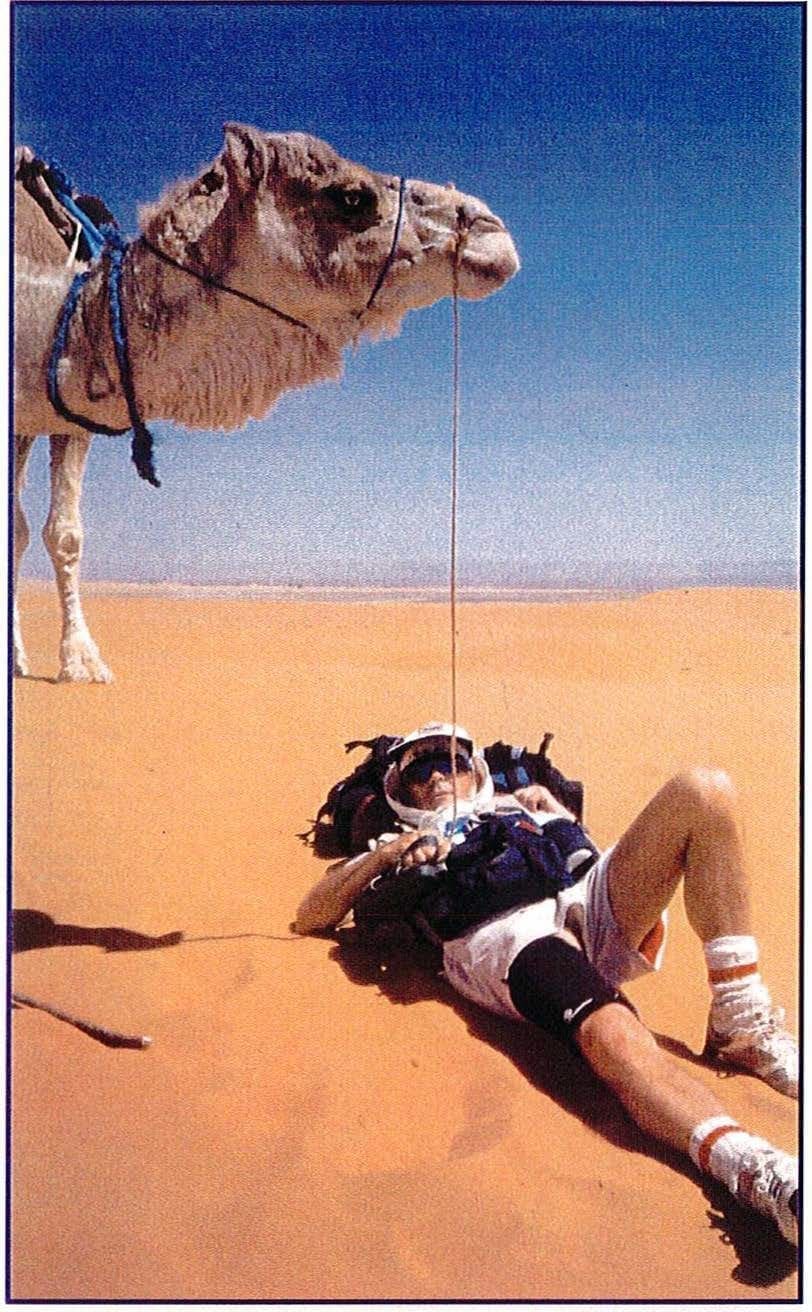

As I waited I wondered if the man beside me was going to live, when help would come and whether I’d get to camp under the time limit, since I was lost. After what seemed like an eternity, a mirage appeared. It grew into a camel with one of the boys riding and the other leading it in my direction. We tried to load the lifeless figure onto the camel but he fell off, again and again. Finally, we laid him across the saddle and tied him down. Just as we were ready to go, a jeep and a moped came speeding toward us along the crest of a sand dune, leaving a small dust storm behind.

The race officials took over and loaded the runner into the Jeep. They put intravenous drips into both his arms. I told them the story and that I’d lost over two hours. They assured me I would get all the time I needed to make it to camp. I was awfully tempted to just get into the jeep and ride back.

With only one day to go, I had to finish the event. I asked for directions and started walking. Three hours later I hobbled into the aid station and saw the downed runner still sitting in the Jeep, IVs in both arms. He was able to talk. His name was James and he was English. He had been overcome by heat and collapsed. He thanked me profusely for saving his life.

At this point, I wanted to quit. I had lost almost three hours. I was exhausted, thirsty as hell, and it was starting to get dark.

The organizers would not hear of it. For every excuse I gave them — too dark, too tired, I would get lost, not enough time left to make the cut-off — they had an answer. I told them to get out of my face and leave me alone. God knows I hated those men at that moment. I wanted so much to stop. They convinced me to go on. They said I could have all the time I needed to finish this stage of the race and that a race official would walk with me while a jeep led the way, so we couldn’t get lost in the dark.

Four agonizing hours later I crawled into camp. It was 10 p.m. Twenty-five runners welcomed me like a hero. It brought tears to my eyes.

The next day, 175 of 200 starters made it to the finish line. I was last but happy to have survived. As for James, I never heard from him again.