Arizona stargazer tells stories about the constellations, promotes astrotourism

I grew up under the stars but not like this. I never saw that many stars, completely untouched by light pollution, brightening up the sky at once. Placing my sleeping bag on the slanted, rocky ground, I climbed in and looked up, only for my eyes to be enveloped by the magic of a meteor shower happening right above me.

- 4 years ago

July 25, 2022

FOUNTAIN HILLS, Arizona — When I got older, I realized stargazing — especially stargazing under dark skies, tucked safely away from light pollution — was a luxury not accessible by everyone.

Growing up, I thought everyone could see the Milky Way from outside their window. The billions of stars swirling above my head in Lewiston, Idaho never seemed like something sacred. I believed no matter where you lived, you could always look up into the dark and see the stars that make up the galaxy we live in.

While technically we’re all blanketed under the creamy Milky Way, the sky I had looked up at my entire life was not the same sky that someone else knew.

Never realizing the luxury of having dark skies as a child

When I grew up and left home, my parents began hosting international students from different countries, most of them college-aged kids from Asia. I remember the story of one boy from Korea in particular.

My parents drove to the airport one night to pick him up. He would be staying with them for a few months. When they exited the airport, the sky was already dark.

“Are those stars,” the boy asked as he looked up at the sky.

My parents said yes, and he replied, “I’ve seen pictures of stars in books. I’ve never seen them in real life before.”

It seems crazy there are places in the world where the stars remain a thing of stories or books; places you can look up at the sky and see at best a dozen stars or see nothing at all. Looking back on it, I realized I took for granted the skies I grew up under. I never learned the constellations (aside from the Big Dipper), and never explored the skies the way I could have.

I had access to something special and lost it. Once I had kids and began home-schooling, I promised myself they would know the galaxy. They would grow up knowing the stories of the stars in a way I never did.

The life-altering experience of stargazing in Albania

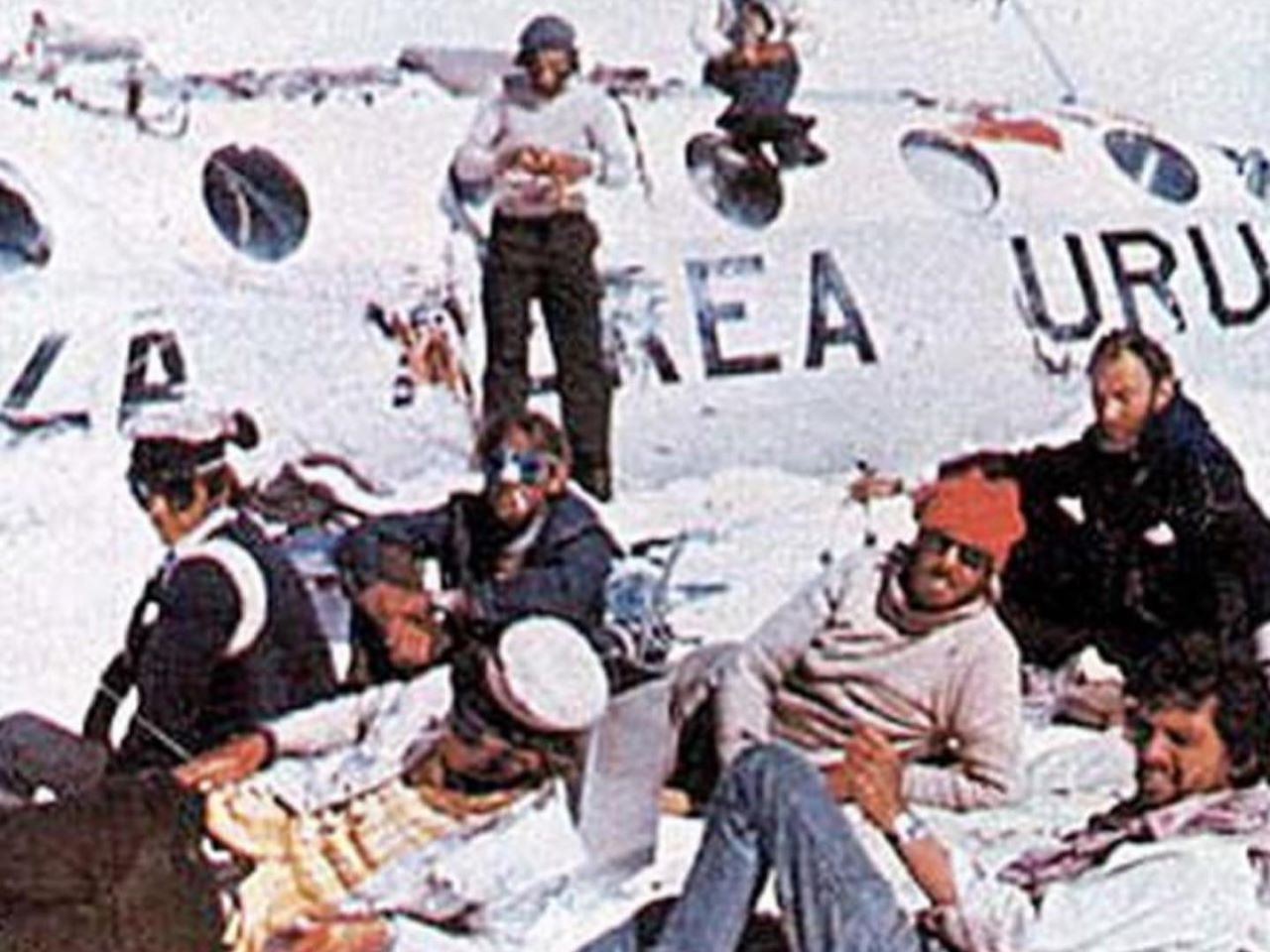

At 18 years old, I traveled to Albania to do some humanitarian work with a group. The trip took place a few months after the fall of communism in the country and the government was going through a transitional period. My groupmates and I traveled to the northern part of the country near what was then known as Yugoslavia. The area continued to experience fighting and violence, but we wanted to see the stars and, finally, our Albanian companions agreed.

They led our group to a hillside in the warm July air. This was not a planned excursion in the slightest and it showed. We had no tents to pitch or camp to set up, just sleeping bags and each other. We would soon return to Tirana, but needed somewhere to stay the night. The thought of sleeping outside did not phase us — we were young after all, so why not?

I grew up under the stars but not like this. I never saw that many stars, completely untouched by light pollution, brightening up the sky at once. Placing my sleeping bag on the slanted, rocky ground, I climbed in and looked up, only for my eyes to be enveloped by the magic of a meteor shower happening right above me.

A revelation about the availability of dark skies

That night, it seemed impossible to get comfortable in my sleeping bag with the uneven ground digging into my back. The warmth of the air added to my discomfort, making it almost impossible to stay inside my sleeping bag, yet I did not dare climb out. Worried by the mere thought of bugs crawling all over me, I stayed cocooned in my sleeping bag, a welcome safety blanket from the elements.

I took comfort in the sky, unable to take my eyes off the meteor shower. Seeing it felt almost otherworldly. It felt wrong to look away, to not drink it in and take advantage of this moment.

“Before electricity, people saw the sky like this all the time,” I thought. “And this is the first time I’m seeing it, at 18.”

I let the sky distract me for the rest of the night.

Protecting and promoting dark skies in Fountain Hills, Arizona

Today, I focus my efforts on teaching people to appreciate dark skies and get to know them. I think many people lived under a dark sky but never knew or learned what to look for.

Since Fountain Hills received the International Dark Sky Community designation, we see people in the community take an interest in it. People take ownership of that part of our community and its identity. Sometimes people even educate their new neighbors on why they should use light in a smart way, avoiding tons of lights shooting up in the sky to brighten their houses.

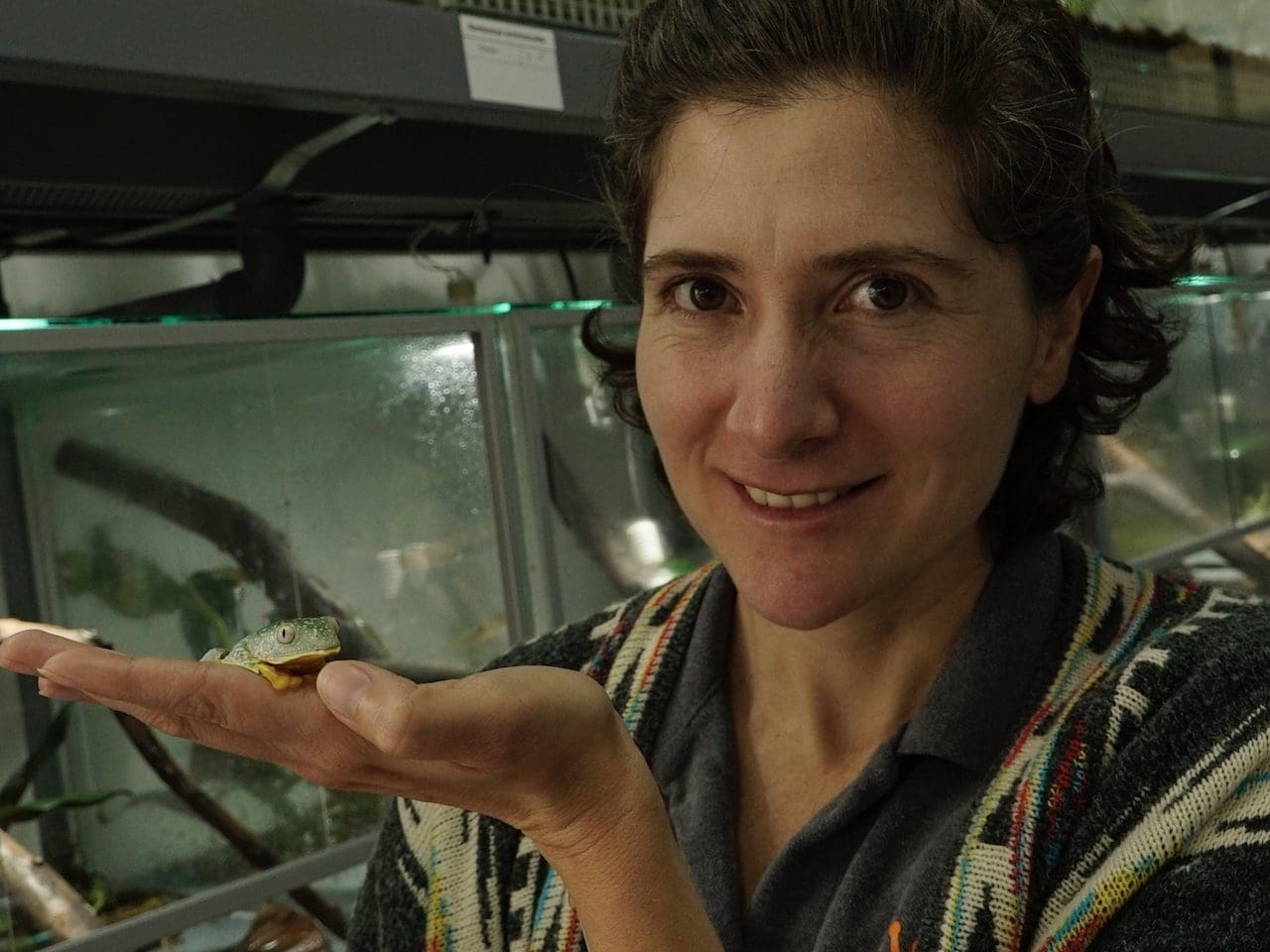

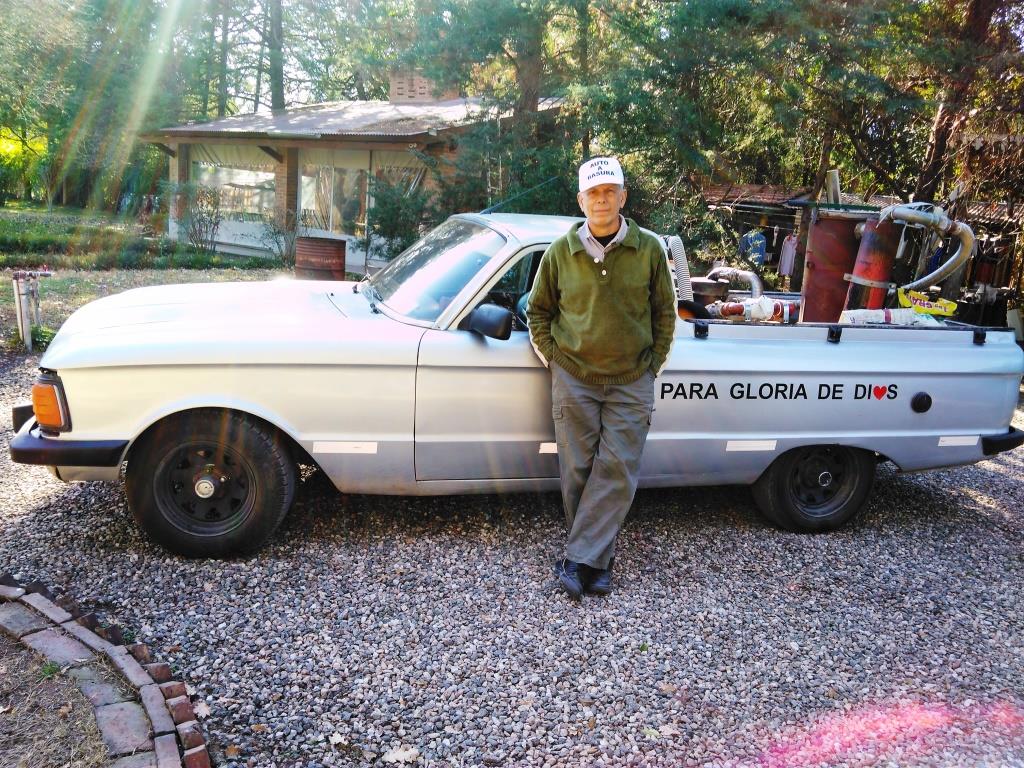

I don’t know if I would call what I do a ‘career’ because I did not see it as one at first. Yet, with each opportunity lined up for me to take advantage of, I experienced a domino effect. Today, when people come to my house in Fountain Hills or I take on stargazing gigs, I tell stories I know about the constellations we see.

Most people know the Greek story about the constellation Orion, named after the hunter. But people in other cultures looked up and saw different pictures that told stories perfectly aligned with their cultures.

I love highlighting those stories because it transports people back to a different time and a culture other than their own; a time when people lived differently and a saw the world around us in a unique way.

When people have a stargazing experience, they may not remember how many light-years away a certain star or constellation is. They remember the story I told, and it stays with them.