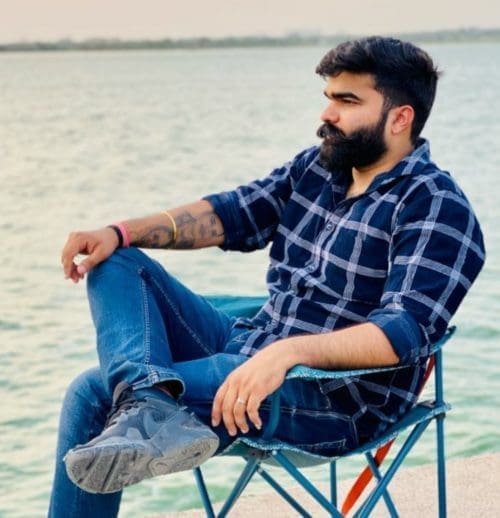

I survived a lightning strike that killed my friend in Jaipur

Vaibhav was knocked unconscious by the lightning strike. I couldn’t see him breathing or moving. I escaped death. Vaibhav died on the spot.

- 5 years ago

August 12, 2021

AMER, India —It was a rainy Sunday.

My friend Vaibhav and I went to visit Jaipur’s Amer Fort [popularly known as Amer Palace]. It is one of the most visited forts in India and a UNESCO World Heritage site.

We intended to go on July 11, after the state government lifted Covid restrictions. Vaibhav’s parents, who lived in Sikar [a city about two hours from Jaipur], asked him to postpone the trip for a couple of days.

He had enrolled in college and was scheduled to enter the hostel [the college’s residence hall]. They wanted to spend more time with him.

Vaibhav was 19-years-old and a first-year law student. He didn’t listen; the lure of fun in the fresh air after months of lockdown was too difficult to resist.

That day, Vaibhav was struck by lightning.

Lightening strikes the tower at Amer Fort, kills tourists

We were taking a stroll through Jaipur’s royal heritage [corridor] when we were hit with a biblical downpour. We saw a magnificent watchtower and climbed it to take a selfie.

The view from the tower was mesmerizing.

About 40 tourists had gathered at the tower and were taking selfies when, out of nowhere, a bolt of lightning hit the structure. There was a big flash of light and a boom. It was horrifying.

It felt like someone hit me in the back of my head. I fell over.

When I looked around, people were laying dead. Women and children were screaming. The tower’s wall had collapsed, and many were buried under it.

My right arm was numb, and I could barely move it. It felt like I had an attack of paralysis. My arm was as stiff as a stone.

The victims were taken to Sawai Man Singh Hospital. Twelve tourists, mostly women and children, were declared dead on arrival. Eleven were treated for critical injuries.

The scene at the hospital was awful. The injured were howling in pain. Some had cut marks on their bodies while others suffered severe burns.

The dead were sent to the mortuary, then to their grieving families. The injured were discharged after being given primary treatment.

Death awaited my friend Vaibhav

Vaibhav was knocked unconscious by the lightning strike. I couldn’t see him breathing or moving. I escaped death, but Vaibhav died on the spot.

It was terrifying. As Vaibhav’s elder, his parents allowed him to go because I was accompanying him. He was the son of my father’s close friend.

Now, he was dead. What would I tell his parents? I had no answer.

Vaibhav died of shock and blunt trauma. His body lay stiff and lifeless in front of me. Now, his parents are devastated; they can’t believe he is gone.

Vaibhav was their only son and they cursed the day he left the house. We lost an extraordinary young man—a bright student who had a great future.

Those 12 lost lives could have been saved if the state government had heeded the Archaeological Department’s requests to have lightning conductors installed.

In addition, the meteorological department is supposed to issue bad weather warnings to tourists. On July 11, when my friend died, the department neither issued the “Orange Alert” nor warned the public of a possible lightning strike.

When I remember that day, I have a simple thought. To Vaibhav, I ask, ‘Forgive me, my friend.’