Cuban teacher fights job bias in Chile

After losing her business to COVID-19, La Dama del Son Cubano fights for her life in Chile.

- 5 years ago

December 18, 2020

SANTIAGO DE CHILE, Chile — Every morning brings an unsolvable problem.

My heart rate begins to rise and the tension in my chest grows. A cool blue light emanates from my computer monitor as I scroll in search of a better life.

Nothing.

I close the page and try to forget. Thinking about my situation only leads to panic attacks that grip me every single morning. It’s a constant anguish.

Being unemployed during a pandemic is difficult to explain. Every day I get up without knowing if I have the resources to make it through the day.

It is useless for me to introduce myself as Miriam Rodríguez Lambert. Everyone knows me as La Dama del Son Cubano — The Lady of the Cuban Son.

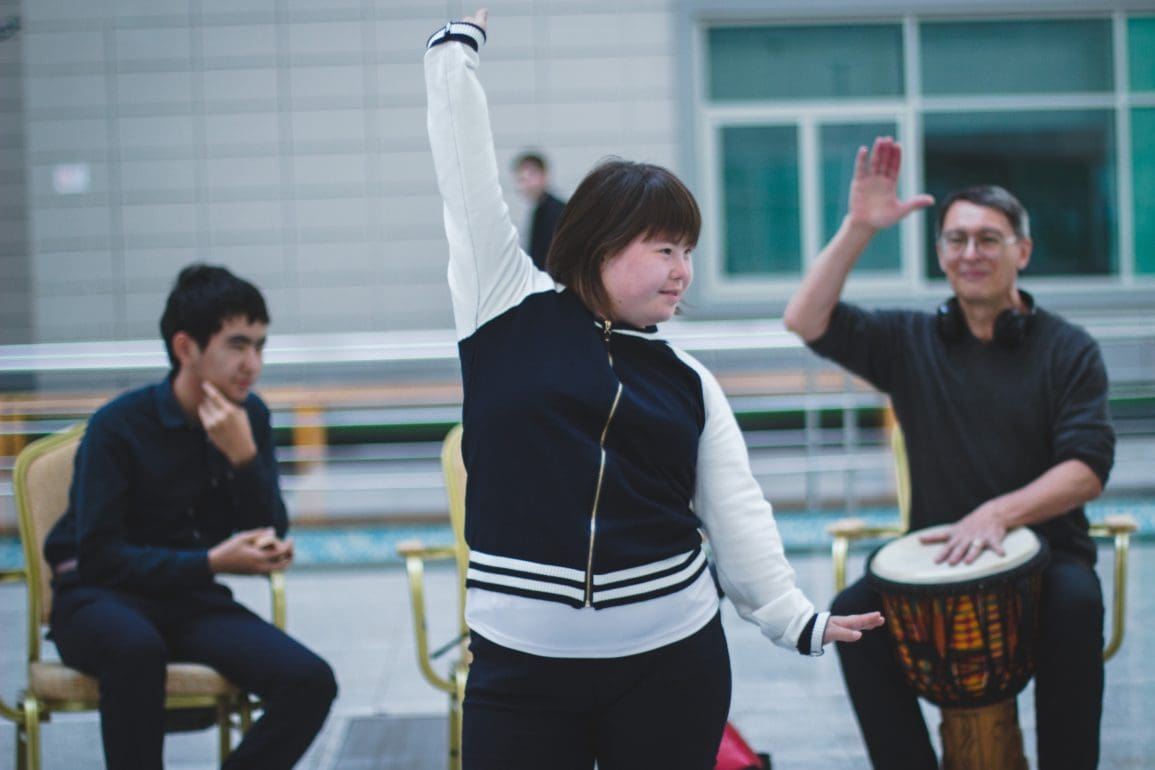

I was born in the Caribbean in Santiago de Cuba — a city where the sun is very strong and people are so happy that one comes to miss them with a nostalgia that hurts. There I studied classical ballet, worked as a professional dancer, and was a teacher.

Though I always strived for something new, for something different. With Cuba as a home base, I began departing for professional and cultural exchanges in 1987. In 1992, I spent time in Aachen, Germany, where I worked at the House of Latin American Culture and the German Folk Ballet Higher Education Center.

Entranced by a desire to know the culture after hearing the stories of Chilean friends, I uprooted again and moved to Chile in 2012.

Now, I live in Santiago de Chile and I have been unemployed for approximately three years.

I live off government aid and the charity of my former dance students.

I don’t know how much longer I can survive in a country where job discrimination is commonplace.

COVID killed my dance

Chile’s “estallido social” decreased the attendance of my dance class, but the arrival of COVID-19 left me penniless.

Every morning, I wake up and turn on the computer to apply for new jobs, submit resumes, respond to potential interviews, and check emails begging for an opportunity.

Every job post in Chile reads the same: “Available only to those under 35 and preferably with Venezuelan, Colombian or Peruvian nationality.”

It hurts to be treated like you are no longer useful. I, with my 58 years, feel good and useful. I just need to be given a chance.

Some employers take advantage of job-seekers desperation and offer extremely low-paying jobs. They close the dialogue with and insulting “take it or leave it.”

Although a constant feeling of rejection invades me, I maintain the illusion of finding a long-awaited job.

After being stagnant for about an hour on the computer looking for job offers, I take free internet courses to avoid the frightening concern that envelops me due to a lack of opportunities.

After a while immersed in the lessons, I feel the same restlessness as before. I get up and wander around the room. Anguish invades me again.

Every day I wonder what I’m doing living in Santiago de Chile — one of Latin America’s most expensive cities. Perhaps I stay because it is the place where there should be more job opportunities. Only, there aren’t any jobs. But, every day, I look. I fight for a better life.

Thankfully, I have a squad of students I call the unconditional who offer financial support. I never imagined that they would be so supportive. It comforts me to think about my group, my friends.

During the pandemic, I had a complicated dental infection. I had a fever, was vomiting, and couldn’t get out of bed. I thought I was going to die. But, the unconditional soon found out and paid for my treatment.

I owe the same to my landlord. My debt to him is not only high but also unpayable. Thanks to his goodwill, I have a roof to sleep under in the middle of this cold city.

I have managed to survive because of these people. I only eat thanks to the food boxes delivered by the government of Sebastián Piñera while donations from the Latin American Parish help me get through the day.

Dreaming costs nothing

My unconditional friend Sisi, a white poodle who looks like a cotton ball with her frizzy hair, is my full-time partner and confidant. She was the pet of a Cuban couple with whom I lived for a while. We grew closer until one day when we became inseparable.

We always go to the same park to clear my head.

The beauty of Chilean parks brings back a flood of emotions. It reminds me of why I came to this vast and beautiful country. Though, I always think about my dear Santiago de Cuba and of my family and friends who remain there.

My chest tightens, it is the fear of growing old from a distance, of eviction and hunger in this expensive but beautiful country.

Sometimes I feel an overwhelming desire to return to my family. But after a while, I tell myself that I’m going to keep trying, at least until I’m 65.