The art of vision

Sight-impaired sculptor draws insight from creative outlet.

- 5 years ago

December 30, 2020

BUENOS AIRES, Argentina—I suffered a retinal detachment in both eyes when I was 25. It started with a gradual loss of vision from maculopathy which took 62.5 per cent of my vision. I now have less than 40 per cent.

I fight every day with my disability. When it imposes something on me, I show it there is a way around the newest barrier, because artistic talent cannot just be reserved for the fully sighted.

I work as a Portuguese teacher in my day job, but drawing is my refuge. It is what allows me to build a world—my world.

I paint with pencils and watercolors. I draw solidarity murals and cartoons. My drawing technique is unique. I bring the sheet almost to the tip of my nose because the edges of my field of vision are fading. I don’t see the contours or contrasts and brightness clouds me but I can perform detail work with the help of a special magnifying glass.

As I draw, I take photos of my progress with my cell phone and enlarge them to see details and detect errors. When something feels unsalvagable, I cut out the good parts and stick them in another background so I do not have to start from scratch.

As time goes by, I find it harder to complete my works. It is difficult to draw with one hand and hold the magnifying glass in the other.

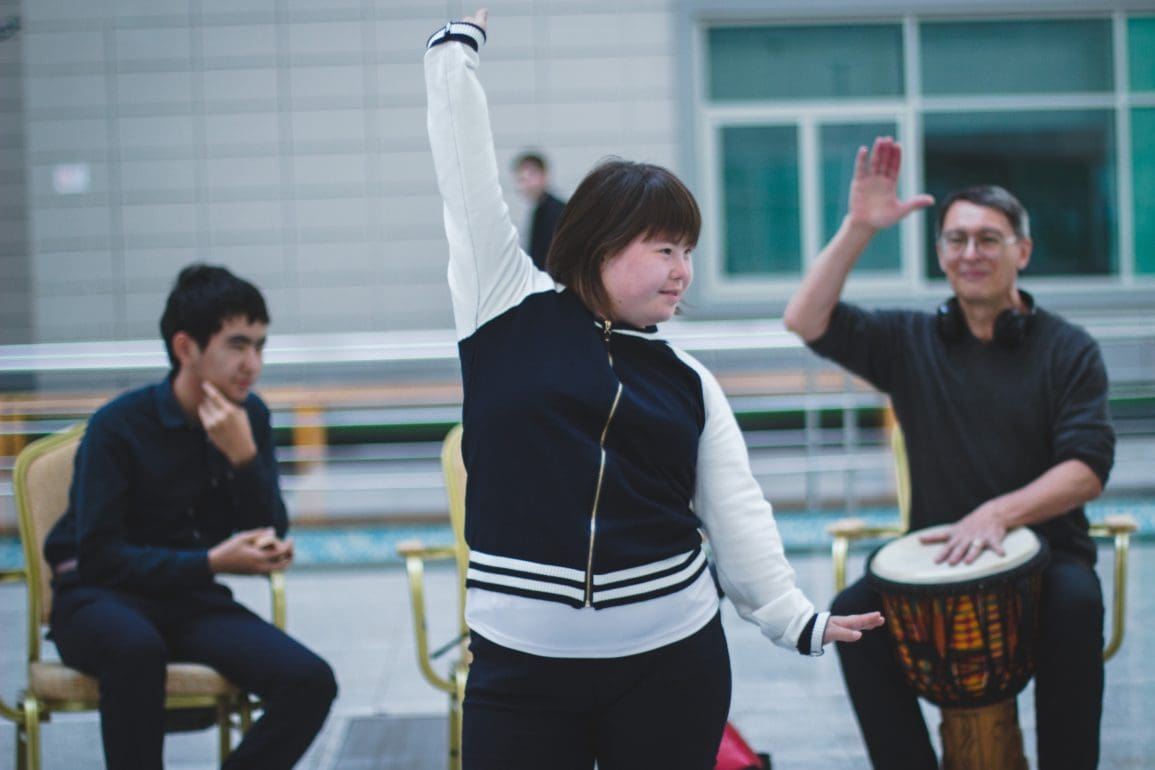

Some time ago, I started working with paper mache to craft figures with colored clothing and accessories. This platform allows me to use touch much more than sight. Whenever we lose one sense, we hone another.

Difficult childhood

I was born on May 21, 1968, in San Cristóbal in the city of Buenos Aires. Doctors said I was a very quiet baby and that I moved little. It turned out to be the first symptom of my high myopia.

My childhood was marked by family conflicts, so I worked at molding a cheerful and sociable personality as a contrast. At school, my teachers saw the potential in my drawings and encouraged me to dedicate myself to art. They told me “I had a very good hand for that.”

My eyesight became the focus after I developed problems reading in school. My parents decided to take me to an oculist where he discovered that I was born with degenerative myopia.

The tension that this ignited led to a judge removing me from my house and sending me to live with the family of a friend for a time. Months later, he awarded my guardianship to my maternal grandmother.

I became emancipated at 17 and since I was already working I rented a room in a house.

A journey that changed everything

One day, a friend asked if I wanted to go and live with them in Curitiba, Brazil. I flew without hesitation. I was never afraid of challenges.

There I worked in a bar where I was also able to sell my drawings. One afternoon, a client approached and offered me a job to work with her in her workshop. Obviously, I said yes. It was an opportunity to learn new techniques.

She worked with leather at the workshop, so I started copying old English hidden treasure maps, spirographing the material. I did a lot of research, looking for any trace of new treasures to be captured in the leather.

By this time, my eyes were deteriorating more and more. My glasses were my constant companion. I never had my eyesight checked regularly and I only changed the prescription of the glasses when I could get a medical check-up. I didn’t feel like it was a concern and I was trying to cope in the best way possible: with a lot of humor.

Surgery and detachment

In Brazil, I met and married a local musician and we went to live in his hometown of São Paulo where I got pregnant. I gave birth to our son Gastón in Argentina.

Back in Brazil, my eyesight was getting worse. There were no longer glasses prescriptions that would allow me to read the fine print from magazines or newspapers. My headaches were increasing and I could not control the dizziness that they caused.

It got so bad that I decided to have surgery at the Hospital das Clinicas de San Pablo, first on my left eye and then on the right.

The surgery on my left eye failed and they diagnosed bilateral retinal detachment with macular involvement on my right eye.

More bad news

I decided to settle permanently in Buenos Aires with my son. There, I sold floor cloths and brooches on the street to pay for our apartment. It was a tough time. We barely had income and I had no way to improve my eyesight, which was getting worse.

I studied Portuguese remotely and managed to get what is called a “Proficiency in Portuguese” from the University of São Paulo which enabled me to teach Portuguese. Our income increased and I no longer had to be selling items on the street.

Things stabilized for a few years before I was hit with another setback.

During a routine medical checkup, doctors gave me the worst news of my life: I was diagnosed with kidney cancer.

At that point, I no longer knew what to think. “Why always me?” I thought over and over again. I was afraid for Gastón, my son. I didn’t want to leave him alone. My world fell apart.

Doctors advised me to settle in the province of Córdoba for the benefit of my health.

I worked as a teacher. Every week, I traveled 12 hours to Buenos Aires to give Portuguese lessons three days a week. I would return to Córdoba to be with my son who was in the care of a family friend.

Special education

I decided to attend the School of Special Education for people with visual disabilities where I learned orientation and mobility. Around that time I also started using a green cane for more security.

I went through a dozen surgeries. No doctor wanted to perform the most recent one because my eyes had been heavily manipulated and I was running the risk of losing my vision completely. There was one angel who did take the risk and that last intervention saved what is left of my vision.

I began to study a Bachelor of Science in Education at the University of Buenos Aires and lobbied hard for people with certain disabilities for better access at the school.

I received my bachelor’s degree at 46 years old.

Show without seeing

I live alone in a small apartment in the La Boca neighborhood. I must have everything in the same place always so I know the location of each item to enable stress-free movement.

La Boca is a very picturesque neighborhood, full of art in its houses, on its walls, and in its people. I admire the strokes of local artists like Quino, Florencio Molina Campos, and Roberto Fontanarrosa.

A friend recently saw my drawings and passed them on to a writer who was looking for illustrations for his soccer storybook. This is how I came to illustrate the book “Otros Ensayos Cuervos” by Pablo Artecona.

I participated in a series “Al gran pueblo Argentino, salud,” where I drew different scenes: a battalion of soldiers in the Malvinas Islands under the snow, the resistance to the Anglo-French squad in the Vuelta de Obligado, scenes of the Cordobazo, and moments of the Bicentennial, among other pictures of our national past.

If I’m feeling depressed, I roll up the papers to prepare them for some work or to paint. It’s a breath of fresh air.

I would love to give workshops in different places to people with disabilities to demonstrate that art heals everything, that it develops the talents we have, that it transports us. The art truly heals.