I kill suffering, not patients when I perform euthanasia

Marcos Hourmann was the first doctor convicted in Spain for practicing euthanasia.

- 5 years ago

August 20, 2021

MADRID, Spain – In March 2005, while working as an ER assistant, I treated Carmen, an 82-year-old woman. She arrived with acute colon cancer, myocardial infarction, and multiple pathologies.

As soon as she arrived, she asked me to end her suffering. “I want to die,” she repeated over and over. I became the first doctor in Spain convicted of practicing euthanasia. The judicial system and society chased and attacked me, but I have no regrets.

They say, “You killed someone.” I say, I killed the suffering, not the patient. I killed the hell she was living in. The patient was already dying.

Helping my patient die was the best medical act of my lifetime. A doctor diagnoses and cures, but when there is something incurable, we also act in the face of death.

People say allowing doctors to manage the death of a patient is an aberration; it is insane. If someone has lung cancer, the only thing I can do is try to operate and cure it. I am not managing death or causing it. Death is already there.

Euthanasia was the right choice for my patient

As my patient Carmen repeated her wish to die, I could do nothing, so I sedated her. I went to rest and, after 50 minutes, Carmen’s daughter called me to tell me she could not see her mother like this anymore.

During sedation, I acted like a doctor does – cold and hoping to stop the pain. Carmen went into multi-organ failure. There was no going back.

Carmen was drowning and unconscious from the mild sedation.

Her suffering, even in sedation, shocked me so much I couldn’t move. I was speechless, looking for answers. Watching her suffer for one more second was pointless. Why prolong her agony?

Instead of sedating her deeply, I decided to end her suffering. I injected her with 50 milligrams of potassium chloride.

In that second, 16 years ago, my life changed forever. Today, I can analyze it a little more carefully and I believe my actions were justified.

The medical director denounced me as a murder, but I did not lose sleep or feel tortured by what I had done.

Losing everything and running from the system

After performing euthanasia on Carmen, I wrote a report stating I had injected potassium. I did not want to hide it. I made it clear that I knew what I was doing, and I did not think it was a crime.

Two months later, my nightmare began. I was sentenced to 10 years in prison and disqualified from practicing medicine for life.

To avoid the charges, I was offered a settlement. If I pleaded guilty, my sentence would be reduced to one year without effective imprisonment and I would be allowed to continue practicing.

Although it seemed like a good deal, it weighed heavily on me because I am not a murderer. In addition, the persecution I experienced forced me to start from scratch at the age of 45.

I had to pay lawyers. I lost my house. My finances were destroyed. I even had to leave the country with my wife Yolanda and my young son Iván. Everything I had was lost.

Then, five years later, someone who knew me was paid to anonymously sell the story. I appeared on the cover of The Sun, nicknamed Killer Doc, and again, I had to leave and start over.

When I returned to Spain in 2010, the subtle persecution continued. I worked in a public hospital and some doctors sent emails to the head of the emergency room informing them of who I was. The following year they did not renew my contract. For years, I had to hide.

My story as a stage production spurs support

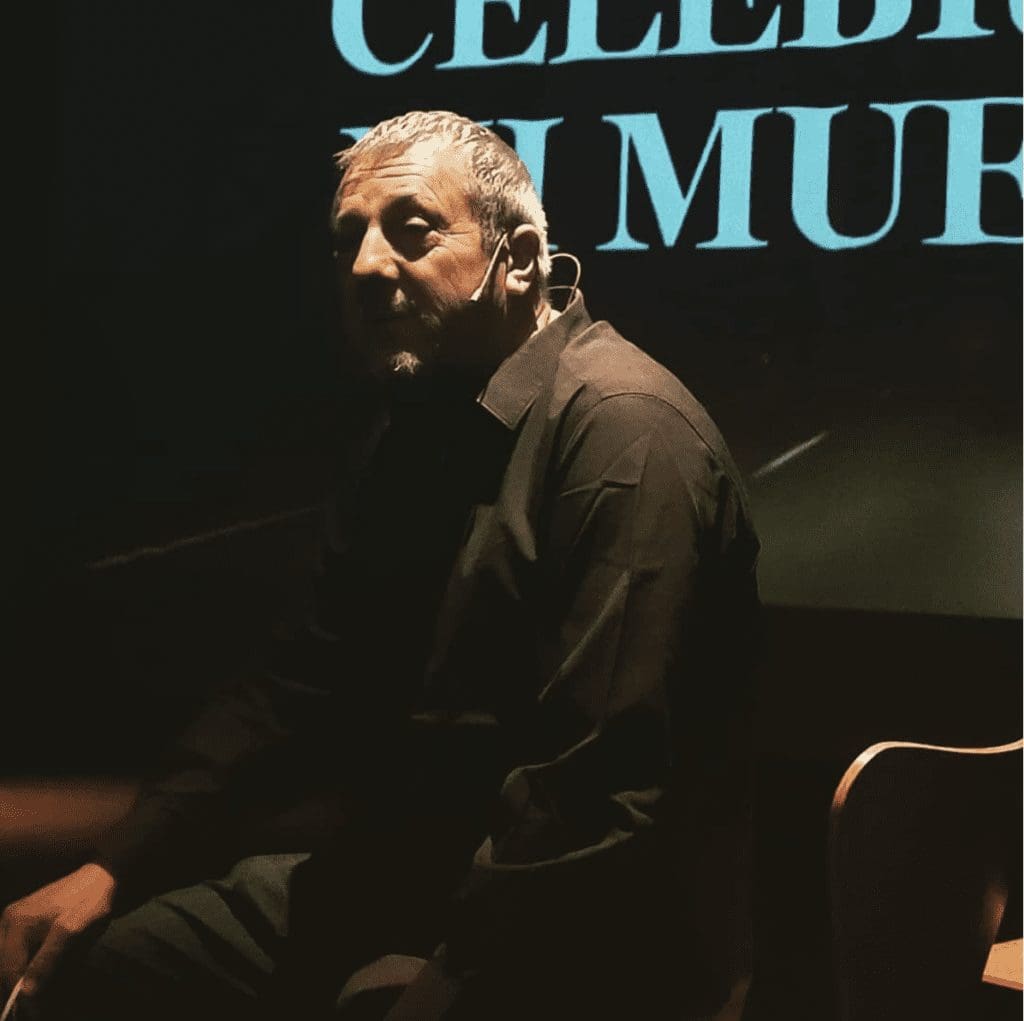

Eventually, I met Victor Morillo, a playwright who wanted to make my story a theater production, and he asked me to be in the play. I didn’t hesitate for a second.

Together with a team, we worked over 60 hours to create “Celebrate my Death.”

Through the play, I began to share my story with strangers. The vast majority who see this play are in favor of euthanasia.

Telling my story causes me no fear. In fact, when one tells the truth, it generates a natural force. At the end of the play, [the actors] have a discussion [about death] that is a fundamental part of the production, and that is very enriching.

This work has resulted in very shocking moments. I have saved all the letters I received into a collection. One of the most powerful was from an 82-year-old grandmother who begged, “Please Marcos, help me remove the mask that I have worn all my life.”

People came to the play in wheelchairs. Cancer patients, including young boys, came wearing handkerchiefs after chemotherapy treatments. We had attendees with ALS, also known as Lou Gehrig’s Disease [a fatal disease of the nervous system with an average life expectancy of three to five years].

After two and a half years and 124 performances, the relationships generated in the 55 minutes of that play cannot be described. Inevitably, it leads to a shocking silence in the room.

I have learned from that experience to listen to people’s silence. It speaks more than if they were yelling.

A different view of death, changing the system

Nobody wants to die, but we all will. This is something we don’t talk about. Although medicine and technology advance us toward immortality, the destination remains the same.

Do you know how your parents want to die? Have you asked them? Understanding this can be a relief.

I don’t want my family to pay half a penny for me to die. I do not want to give money to a system or to pay for a drawer. This is crazy, but we accept it as normal. We have to pay to die.

If I am diagnosed with irreversible lung cancer or pancreatic cancer, I am going to party. I’m going to enjoy life as much as I can; to eat, drink and get high. Later, I will say goodbye to my family at my house, watching television.

I don’t want to be intubated in a hospital. The main way to die today is in a hospital, in a shitty bed. You may not see your relatives, say goodbye, or kiss them. We are so used to that kind of death; it is horrible.

We wear black and link it to death. I love to wear black because it makes me look thinner, but not to die. I want to die in red, blue, and green! Why do I have to die worn out and ruined?

Spain passes long-overdue euthanasia laws

I am so relieved that there is a euthanasia law in Spain now and that my family – my wife Yolanda, my children, my granddaughter, and my ex-wife – will not have to suffer.

The law is not a full reality yet; it is the application process.

While I am the first doctor convicted of performing euthanasia in Spain, and that created significant media coverage, I am an observer now. This has come about through the work of many long-time euthanasia activists.

Mine, along with other cases, pushed politicians forward. I am but a part of the process.

Those who have helped the most are the people who have suffered and have shown us their pain and anguish. They are the real winners in this story.

With the law, a new path is opened. Euthanasia is about not suffering – nothing more.