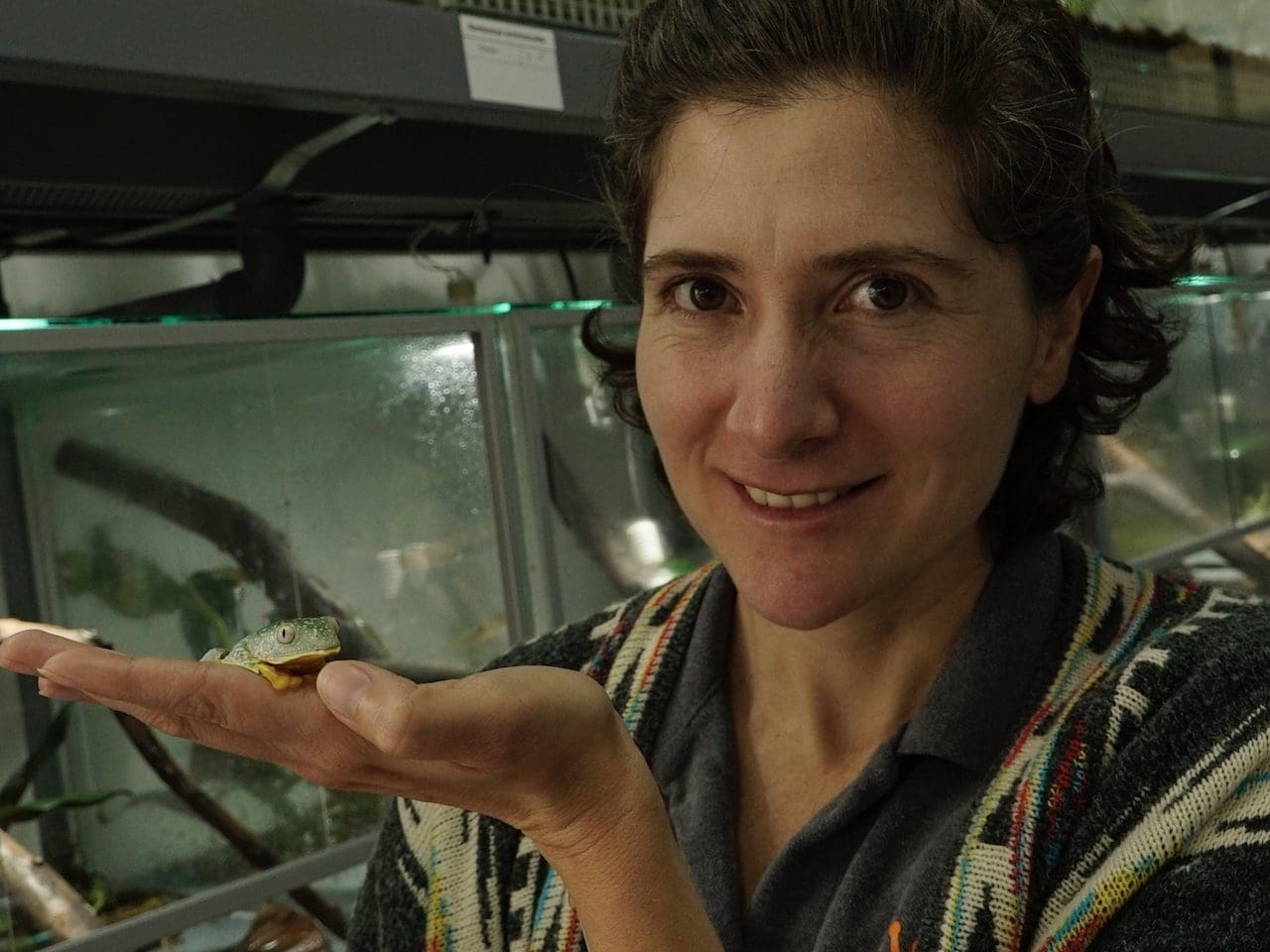

Did you know every human exhale causes pollution? This scientist transforms our breath into biofuels

We often talk about pollution in terms of oil in the sea, burning garbage, or waste coming out of factories. Yet, we forget that on a small scale, each of us pollutes the environment every time we breathe.

- 3 years ago

January 12, 2023

BARCELONA, Spain ꟷ For four months, I dedicated every day of my life to creating a project that would benefit people and the environment – my own personal green footprint. Day after day, I observed my surroundings, when the idea came to me. I wanted to recycle carbon dioxide in indoor spaces and turn it into biofuels. After applying for grants to support my project, I won funding from the European Union and Marie Curie funds.

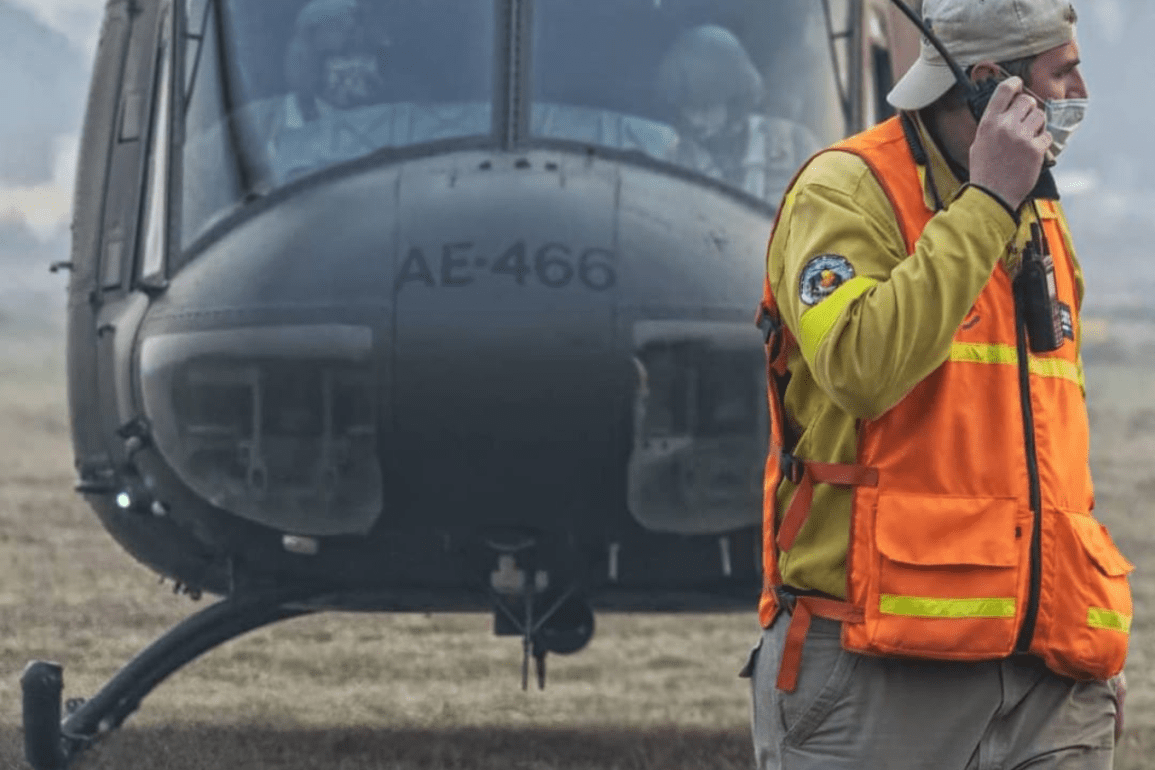

Every day since, I go into the laboratory to work. I put on my uniform, my glasses, and special gloves made of chemical-resistant material. I face chemical exposure every day, but I continue cautiously. In the lab, machines and instruments capture the carbon dioxide – an activity that consume 90 percent or more of my day.

We pollute every time we breathe

I started this project to positively impact people’s lives. As a society, we pollute all the time. We often talk about pollution in terms of oil in the sea, burning garbage, or waste coming out of factories. Yet, we forget that on a small scale, each of us pollutes the environment every time we breathe. As populations grow, we expel more and more CO2 and modern solutions are not enough.

Read more stories about visionaries from around the globe at Orato World Media.

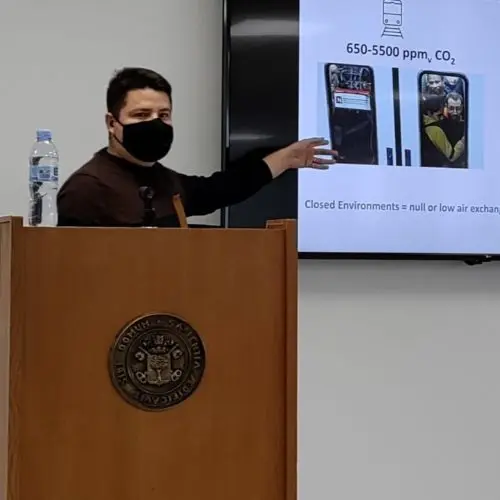

With our grant funds in hand, I built a team of professionals and students to capture carbon dioxide. In the early morning we carry out tests, looking for constant improvement in the amount of CO2 we capture. As we work through the day, I dream of implementing solutions in an office, on a train, or in a room full of people.

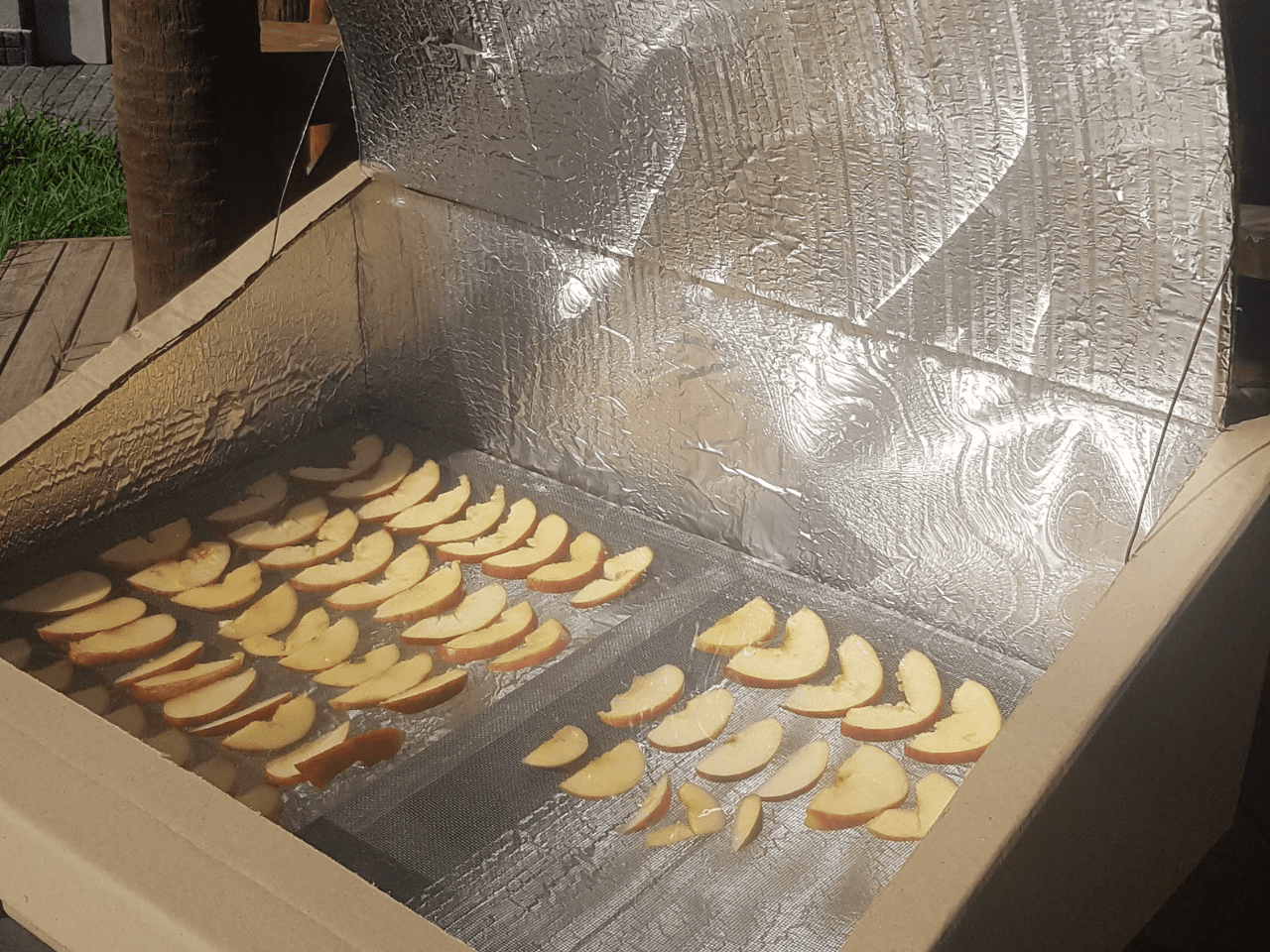

Next, we consider conversion. How can we carry the CO2 to another room and give it an alternative use? As a chemical engineer, I work out ways to concentrate the carbon dioxide, transform it, and release it in a controlled way to create new chemicals or biofuels.

As the CO2 flows into the receptors, it moves through absorbent material, like a filter. A compound inside the filter reacts to the carbon dioxide, causing it to stick, while the remaining air comes out clean. As problems arise, we study and solve them.

Capturing human exhales to generate new fuels

Any research scientist knows the challenges faced in the lab. In the early days of the project, I remember having a problem with the gas chromatograph – an instrument that separates CO2 from the rest of the gases in the air. It took between one and two months to resolve the issue. We used the opportunity to advance other tasks in the project, as we awaited a solution from the manufacturer.

In my career, I have seen important initiatives fail to advance, despite great effort. We fight on, leaning on the encouragement from our colleagues, families, and friends. We remember how important it is to improve the environments where people congregate.

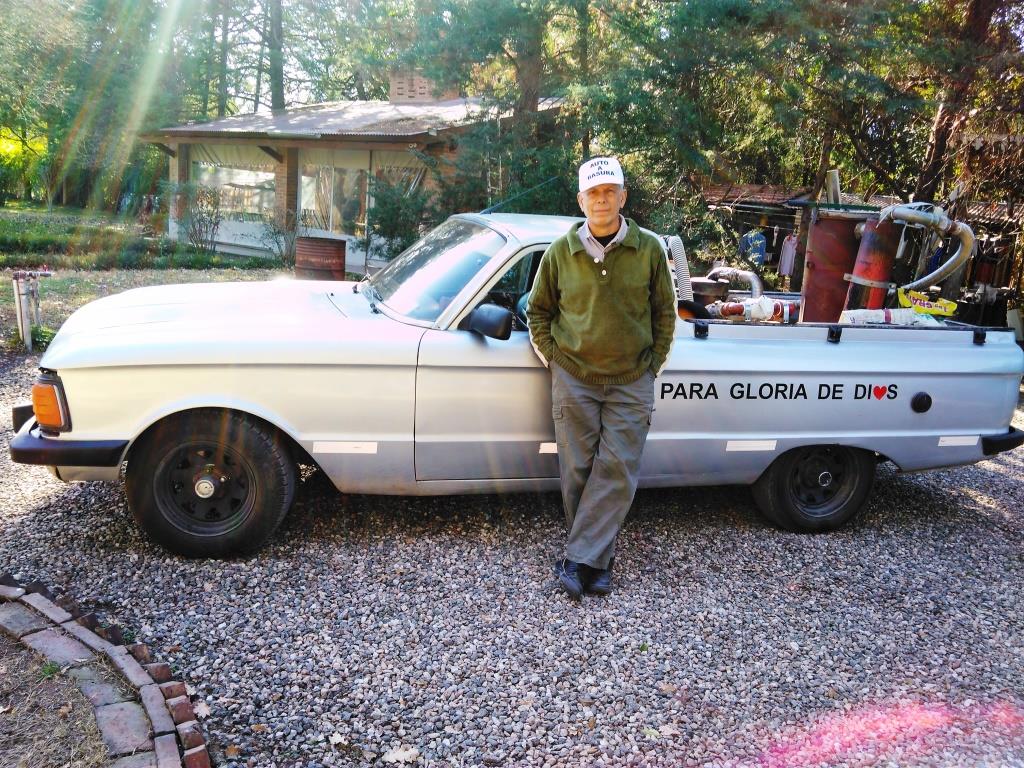

Today, an alliance with the José Simeón Cañas Central American University in El Salvador, we celebrate the arrival of an important new resource. They send us the ashes from the residue of sugar, rice, and cashew seeds. The material helps us capture the minerals we need to transform CO2 into something else. A simple act like shipping ashes from El Salvador to Spain has strengthened our national solidarity.

I know now that my work can cross borders. The benefit of a project like this [is to remove the abundance of carbon dioxide in populous places. We seek to turn it into a product that, for example, feeds combustion boilers; or other fuels that will not have to be generated from fossil origins.] We continue day after day, in the hopes of leaving our own green footprint.