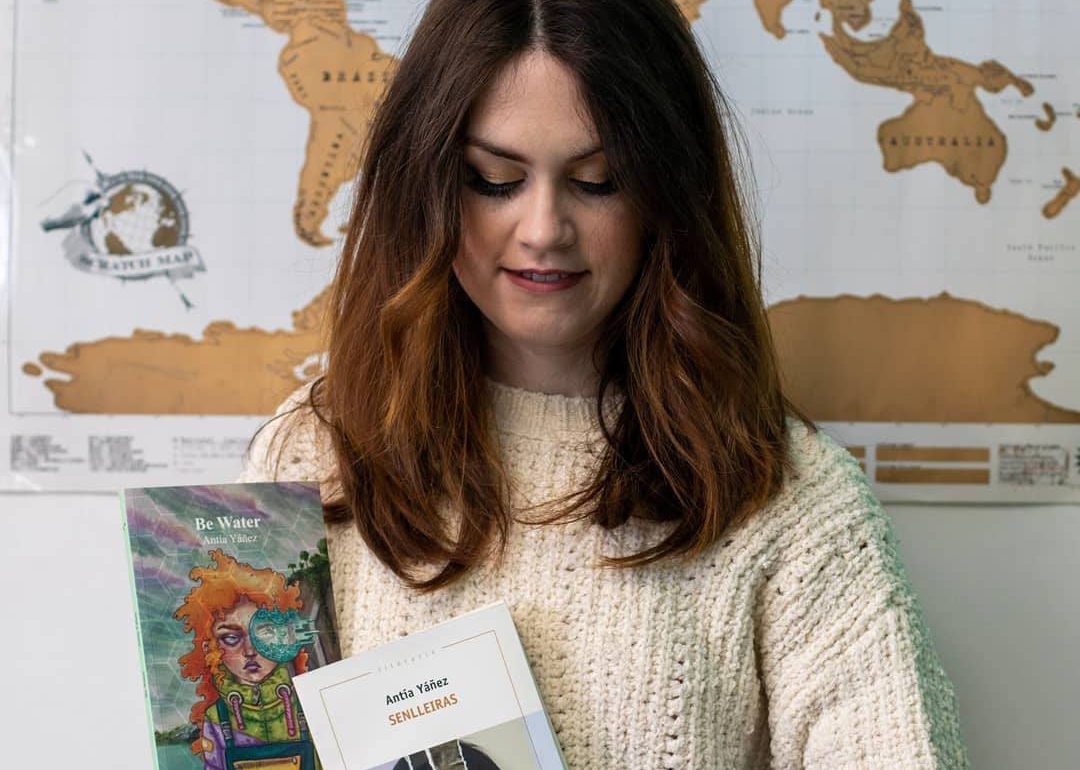

Woman with ALS details the progression of the disease, dreams of euthanasia

Ideally, [when I die] I would be surrounded by my closest friends, Laura, and my granddaughter, while listening to bossa nova music like I used to do with Hugo. Regrettably, such a scenario remains impossible… Nonetheless, I persist in exploring options to bring about my death here, while simultaneously advocating for the passage of a law that would enable a more accessible approach for those who desire it.

- 3 years ago

July 2, 2023

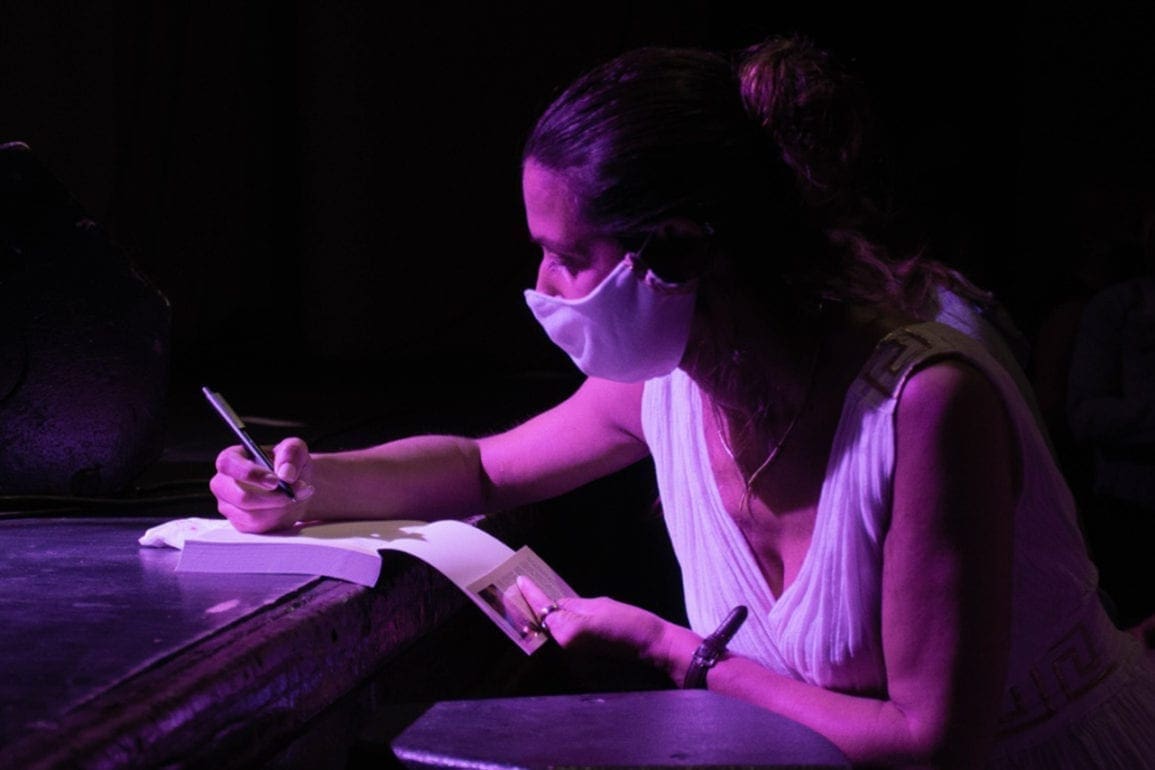

BUENOS AIRES, Argentina — I feel imprisoned in my own body. My brain still functions, but it remains trapped in my disease. For the past five years, I have battled Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS).

My impending death looms near and unless I take action, it will prove a dreadful experience. The physical pain, while bearable, pales in comparison to the profound mental anguish I endure. As I witness the relentless progression of my disease, minute by minute, I wish for euthanasia.

Read more stories in the Health category from Orato World Media.

Anguish and curiosity consumed me as I discovered by disease

Throughout my 65 years, I enjoyed a vibrant and healthy life. I cycled extensively, exploring new places, and I swam with great enthusiasm. One day, during an aqua gym class in the pool, I sensed a stiffness in the soles of my feet. It proved a foreboding sign.

Soon after, my balance began to falter. Within a year, I inexplicably fell backwards on 33 occasions. One day, as I started washing my hands, I fell backward and found myself submerged in the tub. It felt as though I no longer had control over my own movements. It terrified me, and the worst possible thoughts formed in my mind.

I sought help, consulting several traumatologists, but none seemed to grasp the gravity of my condition. It became apparent to me that something peculiar was transpiring. Drawing upon my background as an anthropologist and my experience with science, technology, and medicine, I embarked on an independent investigation.

I scoured national and international journals for relevant papers on ALS. As I delved deeper, I realized I exhibited more symptoms than the 10 typically associated with the disease. A tumultuous blend of anguish and curiosity engulfed me. I was losing control of my own body and there was nothing I could do.

I watched my own father go down a similar path

Never before in my life had I experienced illness. I had never been confined to a hospital bed. As I poured through papers until dawn, my husband Hugo, grew apprehensive. He genuinely cared and wanted to shield me from my distress. For me, it felt like an insatiable thirst – an unyielding desire to comprehend the unfolding mystery.

All documented ALS cases relentlessly conclude with death. No statistic or percentage of patients emerge victorious from its clutches. I knew I would not be the exception. Upon grasping this reality, one pressing question echoed in my mind: “Why me?” Alas, it yielded no answer.

I come from an atheistic family. I myself am an atheist. Within my belief system, I incorporate the evolutionary aspect of anthropology, so death does not scare me. However, pain does. My psychological pain feels overwhelming. I feel forced to depend on others for absolutely everything.

My own father, who worked as a doctor, slowly suffered from Alzheimer’s starting at 65 years old. He lived like this for 10 years. He asked his colleagues to sedate him when he reached the terminal stage. When my mom and I found out, we agreed. Dad already had kidney and bladder problems and remained absent from life. He died in his room.

Mom and I laid next to him, one on each side. He seemed very agitated until his friends sedated him. Then he relaxed and died peacefully. Since 1993, I never felt remorse. It was what he wanted and needed, and it felt like the right thing to do.

As I go about my day, a strong sense of shame engulfs me

At present, I rely on a team of seven caregivers. Within the confines of my home, at least two people remain by my side at all times. They provide assistance with personal hygiene and accompany me to the bathroom. These caregivers hold the books I read, cook, and tend to almost every aspect of my daily life.

Despite my physical limitations, I persevere in my work and research, delving into a plethora of resources. I possess a meticulous knowledge of the location of each book in my library, yet it pains me to depend on others to retrieve them. Verbalizing my emotions surrounding this predicament proves arduous. The situation itself transcends my ability to articulate myself. Internally, I harbor a great deal of anger for my inability to be self-sufficient.

Over time, I developed an economy of speech simply because it demanded considerable effort to talk. I prefer to conserve my words, thinking of the wisdom of the anchorites, who practice silence for the sake of silence. I no longer engage in the dynamic exchange of conversation with others. My withdrawal can be misconstrued as an inability to speak.

Despite these hardships, my desire to be active persists. I believe the life force remains intact until the very end. Yet, when confronted with the harsh reality of my situation, frustration sets in. It often reaches overwhelming proportions. This disease is akin to a process of mummification, as the cells responsible for driving neurons, which in turn control non-cognitive motor functions, gradually wither away.

Getting euthanized remains a challenge in Argentina

The simple act of getting out of bed, even with the assistance of two individuals, can take up to three hours. I remain unable to turn over independently. Through massages and kinesiological exercises, they manage to reposition and lift me.

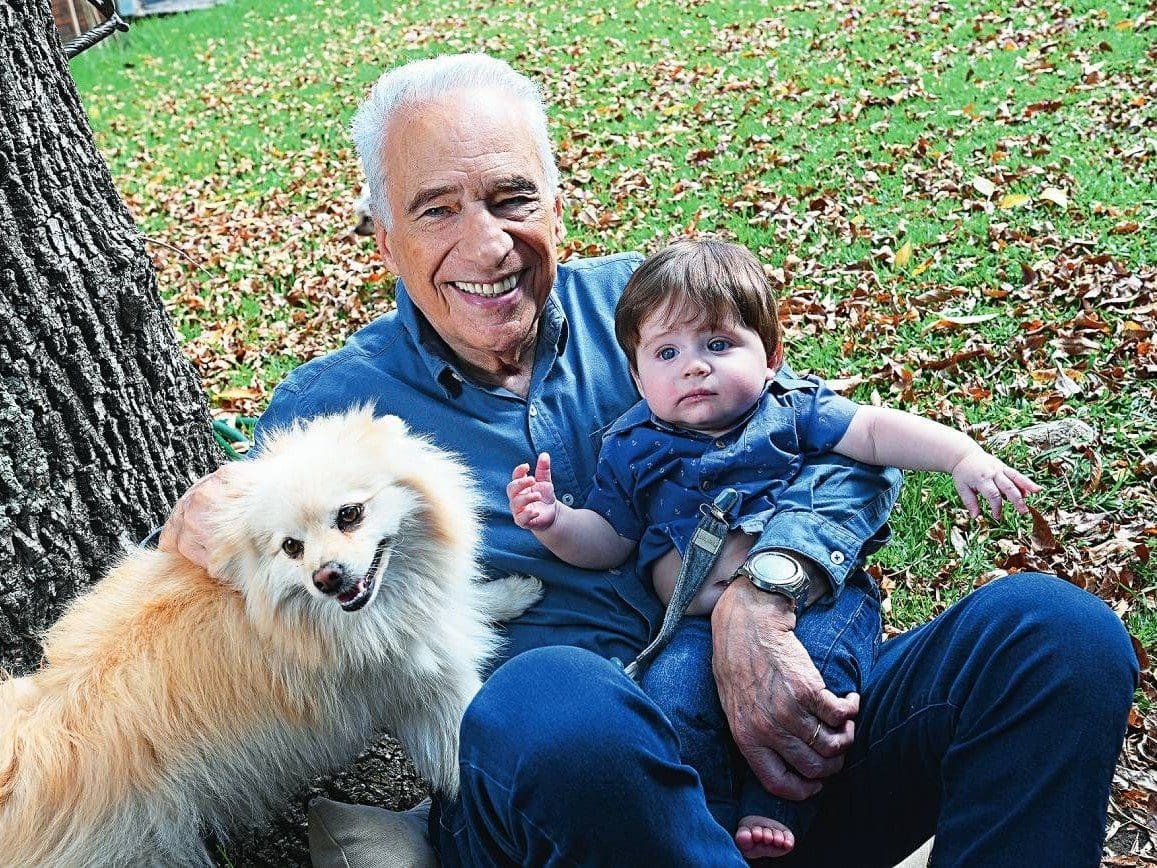

My symptoms started in 2018, and I was diagnosed in 2020. Yet, I believe my life ended in 2021 when Hugo died. It felt like two atomic bombs exploding at once. He gave meaning to my life. At that time, the disease was not yet advanced, and I felt more independent. With him there, our lives revolved around play, support, camaraderie, and love. His departure broke my heart.

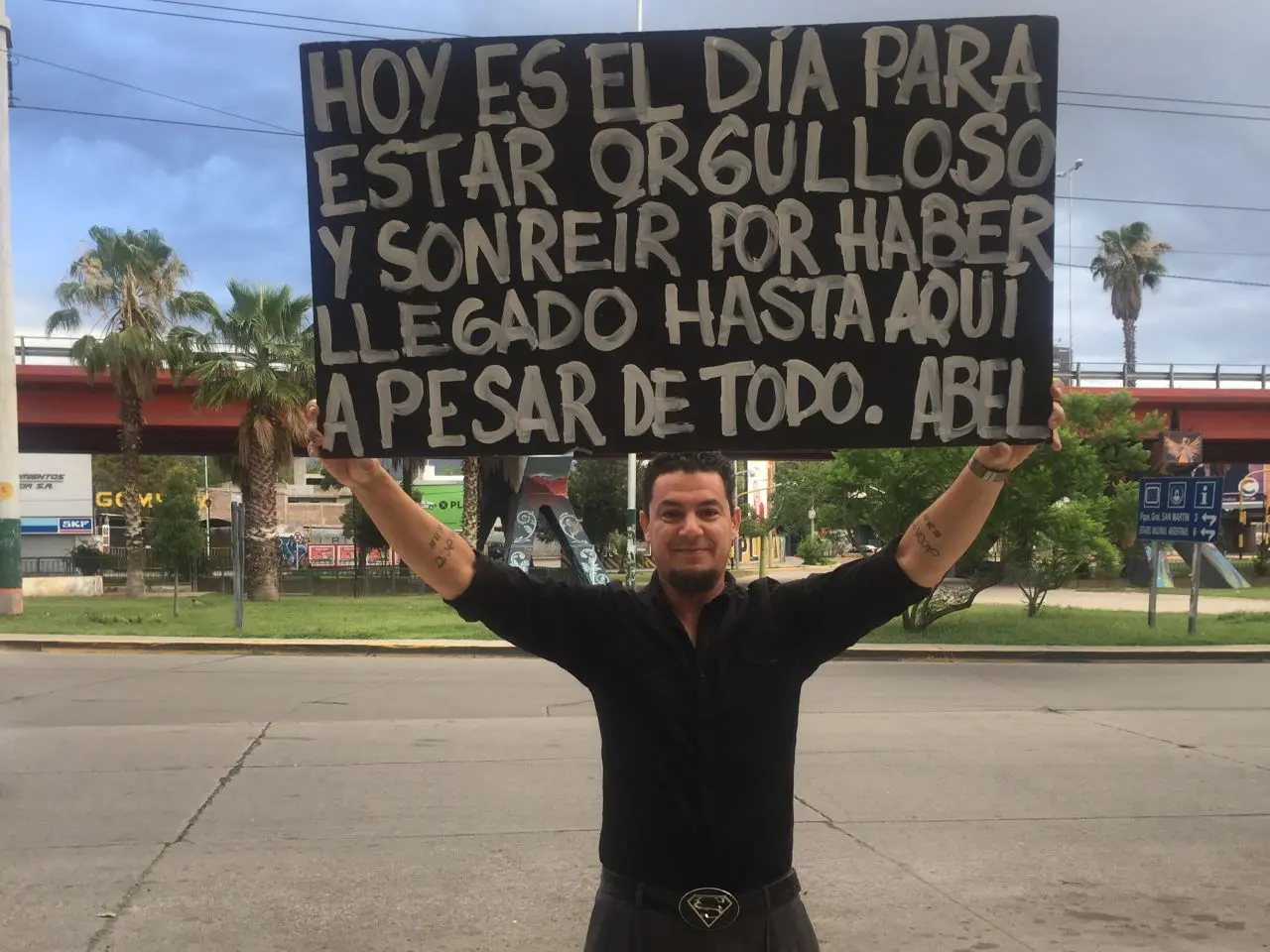

Our only remaining family is Hugo’s daughter Laura, and her daughter, who often visit me. I thought of going to Switzerland, where assisted suicide remains legal. However, the notion of passing away in a foreign land, distant from the people I hold dear and who love me, does not sit well. Ideally, I would be surrounded by my closest friends, Laura, and my granddaughter, while listening to bossa nova music like I used to do with Hugo. Regrettably, such a scenario remains impossible.

Several months ago, when I had the opportunity to be sedated, the doctors requested a family member be present. Laura declined to participate, as she considers it a crime. She does not wish to be involved in such actions in Argentina. I respect her stance, as it aligns with her principles.

Nonetheless, I persist in exploring options to bring about my death here, while simultaneously advocating for the passage of a law that would enable a more accessible approach for those who desire it. Time is not on my side, unfortunately. My illness continues to progress at a slow but relentless pace.