Fight against female genital mutilation lasts a lifetime

When they cut me, it left me with extreme pain, excessive bleeding, shock, and genital tissue swelling.

- 5 years ago

May 3, 2021

ILOODOKILANI, Kenya — Female genital mutilation (FGM) in the world is causing an uproar despite many government authorities banning the practice.

I am a victim of female genital mutilation. I know and understand all the pain of not having rights to your own body as a woman growing up in communities chained on culture.

The cut left me bleeding for days, and as young as I was, the pain was intense and unbearable. Until today, every time I remember my cut experience, my body feels the pain again as my heart beats a little faster than usual.

They circumcised us against our wish. No one gave us the right to choose whether to be cut or not; they just did it to us.

Rite of passage

Some communities still practice it as a mandatory rite of passage in Kenya, even though government authorities outlawed the procedure.

I have been on the front line in my community, fighting for young girls’ rights and protecting thousands of them from female genital mutilation and underage marriages for 30 years.

The fighting journey has been nothing but one with ups and downs. I come from a community rooted deeply in traditional cultural practices, thus making it a challenge for them to accept female genital mutilation as a harmful practice.

I have been criticized and ousted by my community, terming me as a cultural traitor and radical. They don’t want to listen or let go of the practice despite its being clear on their faces how female genital mutilation can harm and affect young girls.

They have seen with their eyes young girls dying and others left with serious health issues after undergoing the cut but still don’t want to let go of the cut. The young, innocent girls are the ones left to carry the painful burden.

Pain of the cut

FGM is something that the community embraced as a sign of womanhood. If you did not have the procedure done, you did not belong.

When they cut me, it left me with extreme pain, excessive bleeding, shock, and genital tissue swelling due to inflammatory response.

For several months I could not perform some duties due to the pain of the cut. I could feel my body was on the verge of being paralyzed on one side.

I tried to ignore the pain, but it was too intense for me to forget. My parents and especially my father, didn’t care about how I was feeling.

All they wanted was for me to be cut and get married as a young girl and protect the culture at the expense of my life.

I have carried all those painful memories all through to my 70s because it hurts so bad.

Fighting against FGM

My fight against female genital mutilation in Kenya started nearly three decades ago when I was 30 years old.

I was so disturbed by the practice, especially when I saw young girls suffering the brunt of the cut.

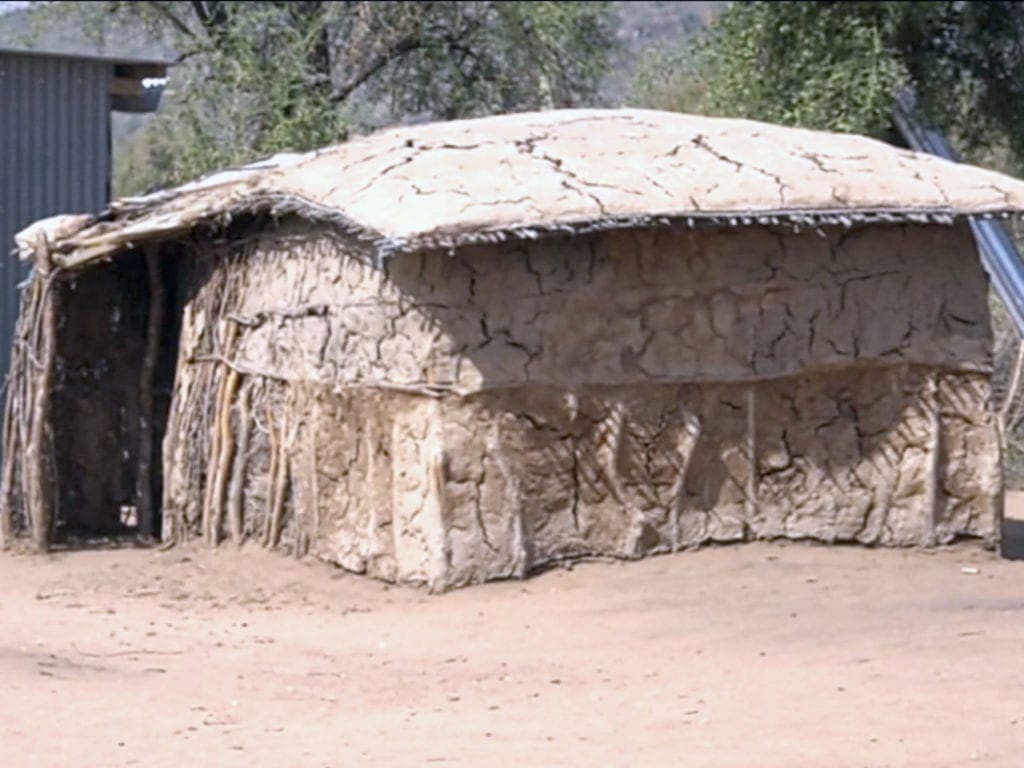

One evening at my tiny house made of mud, I heard women screaming. The screaming caught my attention, making me rush to where the screams were coming from, not far from my homestead.

Upon arriving, I found out a 12-year-old young girl had died after bleeding for almost one hour after undergoing the cut.

Heartbreaking sight

It was so painful and heartbreaking to see a young girl’s body full of hope and future lying down dead in a cold room, never to wake up again.

I could feel the pain in my heart as the young girl’s mother cried helplessly, not knowing what to do to bring her daughter back to life or go back to the days before her daughter underwent the cut.

As I stood there, my voice to fight the stubborn taboo was born.

My mind quickly went back to the pain I felt when they cut me, and at that moment, without fear of favor or contradiction, I wanted to know the people behind that cut that left the young, innocent girl bleeding to death.

I finally found out they cut the young girl to be married off to a wealthy Maasai man as a third wife in my search for answers.

The father was behind all that had happened. I decided to report the father and the women who practiced the cut to the authorities in the area.

The officers handled the case and gave a limp “warning” to those practicing female genital mutilation to underage girls who are still innocent, like the dead 12-year-old girl.

Step towards justice

With my community rooted deeply in cultural practices, the “warning” was just a step towards justice for thousands of girls in my community, who underwent cuts without being given the power to choose.

That was the beginning of my journey as a female genital mutilation activist in my community.

The community turned against me, blaming me for breaking the cultural norms and going against the elders to fight a practice that has been there for ages.

But with no fear of what I will face through the journey as an anti-FGM activist, I moved on and started a journey of creating awareness of the dangers of female genital mutilation and how it affects the lives of young girls and women in the world.

My cut experience became my testimony of educating the community on how the cut can ruin lives in many untold ways. It was not an easy task because the community was so hard on letting go of the stubborn cultural practice.

Ray of hope

Time passed, and a ray of hope started shining.

Several women in the community started gaining voices to fight against the stubborn practice which had become a thorn in the flesh. Together we become powerful, and our voices become our weapon in protecting our rights as women.

We rescued young girls from being cut and married off at a young age. Those found guilty of practicing the cut to underage girls were arrested and summoned for going against the rights of young girls.

With our voice, the young girls become more aggressive of their rights despite being forced into underage marriages and female genital mutilation, practiced under darkness.

So far, the fight has been that of mixed-status, both failure and success, but I hope soon even those practicing behind the scenes will be brought to light and face the consequences of practicing the cut to young girls.

Covid-19 impacts

The Covid-19 pandemic has taken a toll on many things, including the country’s economy, which is far worse affected. Many families are struggling to survive with the virus hitting many. It has also caused a devastating impact on females.

Domestic violence is on the upsurge. Teenage pregnancy rates are rising, with early child marriage increasing in every part of the country.

This downward trend has also revived cultural practices like female genital mutilation, which has been on an upswing since the first lockdown in march last year in Kenya.

The lockdown and school closures left many girls at home, making many vulnerable to genital cutting in communities that see the practice as a prerequisite for marriage and as a rite of passage.

Schools as sanctuaries

Many girls are typically protected and shielded by being in school, which is an alternative to marriage.

Many are at boarding schools where it’s hard for them to undergo the cut. But at home, these girls are not only being cut but are being forcibly married off at a young age.

People still see female genital mutilation as an investment in the girl and her ability to be married off, and that’s why many families are doing the practice.

The virus has affected our efforts to fight against the cut badly, but we haven’t stopped trying to create awareness and take action against those practicing the cut to young girls.

I work closely with the community on educating people about the dangers of the practice and fostering dialogue on changing societal norms and behaviors that perpetuate harmful practices like this and child marriage.

I ensure that they bring all of the culprits of female genital mutilation to justice, and they face the consequences of forcing young girls to undergo this practice that continue to harm our young girls.

Kenya’s fight against FGM

The government supports my effort in the fight against female genital mutilation in Kenya. In Kenya, doctors circumcise at least one in five females aged 15 and 50 despite a ban on the practice enacted in 2011.

Any girl who refuses to undergo the procedure is declared an outcast by the community. This pressure creates fear in young girls forcing them to choose the path of circumcision for fear of being outcasts. But the government of Kenya’s effort in being serious about the matter has been a boost.

In 2019, Kenya’s President Uhuru Kenyatta vowed to end the stubborn practice by 2022. Many at the time saw it as an unrealistic goal for it being something held dearly by communities with retrogressive culture.

Much-needed boost

On March 17 this year, Kenya’s High Court upheld a ban on female genital mutilation, giving us a much-needed boost on fighting to end the widely condemned practice.

The landmark declaration is a win in the fight against the practice, which has for years caused severe health consequences to women and girls in our nation.

With the ruling upheld, I am confident we will eradicate the stubborn practice, and women and girls will be free from the chains of traditional methods that have been holding them.

This action is also a good sign that as a nation. We are closer to the goal of protecting girls and women from harmful traditional practices.

Just a pipe dream?

The United Nations Children’s Fund (Unicef) estimates that at least four million girls and women are at the risk of female genital mutilation every year, making the Global Goals of ending traditional harmful practices like FGM a pipe dream.

With different agencies joining the global fight against female genital mutilation, I am optimistic it will soon be behind us.

When that happens, all girls and women will be free from the chains of this archaic procedure that has harmed thousands of women like me in the world.

For fighters like me, may we never get tired of fighting and advocating for our rights as women. Let’s fight for ourselves and the next generation of young girls in the world.