COVID-19 orphan becomes child laborer, raises minor siblings

I had little bandwidth to deliberate on my loss and what it meant. But I could feel abandoned, lonely and anxious.

- 5 years ago

July 23, 2021

Names have been changed to protect the identities of the interview subject and his siblings who are minors.

SHAMLI, Uttar Pradesh, India — After my father died of COVID-19 in April last year, my mother would wrap her arms around my siblings and me, hide her tears and pain, and tell us he had gone to work.

I couldn’t understand why it took him so long to come home. He was a farmer. He never left us.

I was still trying to cope with his absence when my grandparents died in quick succession in December. Then, life struck its harshest blow. Four months later, I lost my mother to Covid-19.

My siblings, Geeta (12) and Veer (11), and I were suddenly all alone and still in lockdown, left to fend for ourselves.

The devastation of losing my family to COVID-19

I was never told that everyone dies; that I would have to face a day without my parents – a day when I couldn’t see them, touch them, or feel their love. I was never told that it is the natural order of things for parents to die before their children.

In just one year, both of my parents, who were my lifeline, were gone. When I heard the neighbors refer to me as an orphan, I was taken aback.

With little ability to deliberate on what this loss meant, I felt abandoned, lonely, and anxious. My parents provided us a safe harbor and made us feel at ease in the world.

I remember Geeta telling me, about a month after our mother died, “I wish I could hug Ma right now. I miss talking to her. I miss her food. I wish she were here.” We hugged and let the tears roll down our cheeks.

As I looked for answers, I questioned friends whose parents had died. I asked, “How does it feel to be an orphan?” Everyone I talked to was as clueless as I was, experiencing an enduring sense of loss.

I watched some of my peers receive love from their parents and it made me feel all the more disconnected. My mother had always been my most fierce defender, regardless of the situation. My father was my advisor. Fate could not have dealt a crueler blow, but worse was in store for us.

Orphaned and on lock-down

The neighbors began shying away from us, withdrawing support for fear of catching COVID-19. Strangers made comments about us. They felt sorry for us, but I didn’t want their pity. I needed compassion.

We stayed confined in our house for a month. Geeta cooked the food and Veer helped with cleaning. It was terrible. They were supposed to be studying, yet here they were dealing with grief and trying to survive in a harsh world.

None of our relatives or neighbors could visit us to extend condolences due to the lockdown. Entry into the lane of our house had been cut off and we were put under isolation.

We couldn’t go out to buy rations, and we didn’t have access to clean water. Despite promises, no one from the Child Welfare Committee came to our house to sanitize it or check if we were doing alright. It was a struggle for us to stay indoors.

My father was a farmer with nine bigha (5.6 acres) of land and five buffaloes. He grew sugarcane and wheat in the fields. After he was gone, there was a lot to be done. The farm and cattle had to be managed. The finances had to be sorted, but I had no one to help us.

In tenth grade and raising my siblings alone

Our lives are in disarray. While my siblings and I didn’t sign up for this, we are dealing with it together.

Geeta is in ninth grade, while Veer is in seventh grade. They are bright and diligent students. Unfortunately, their dreams have been shattered. The truth is we will grow up without a father and a mother, but I will ensure that my siblings’ lives are not scarred forever.

I will ensure that their education is not impeded, that they dream, and live happily. I work hard to take care of my siblings and secure their futures.

Geeta still cooks, but she studies online in the afternoon. Veer helps with cleaning, but he learns new skills and keeps abreast with his lessons in the evening.

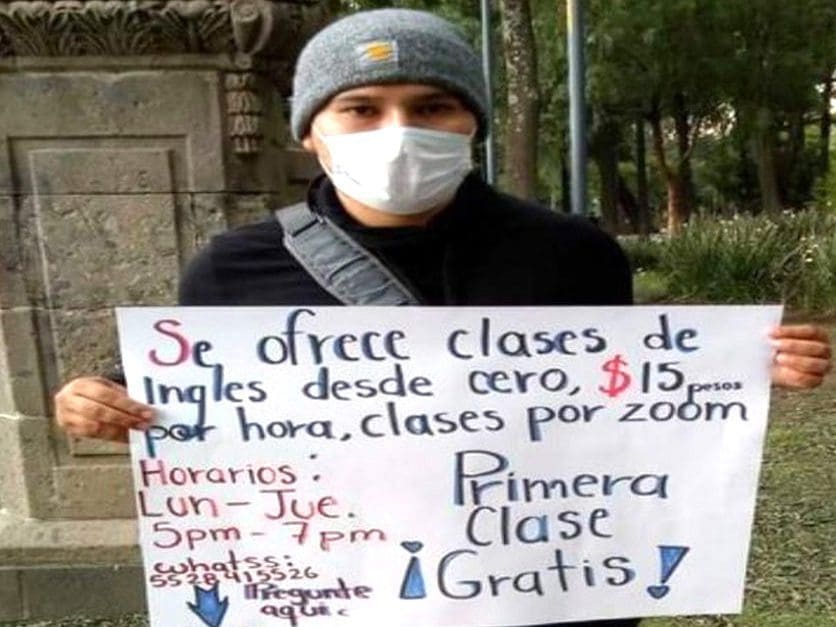

I am in tenth grade. I plow the field in the blistering sun and take online classes at night.

Hunger hangs over us

Kids my age don’t have to worry about paying school fees. I know I am engaged in the worst forms of child labor, but if I don’t do it, we will die of hunger.

When the neighbors see me in tattered clothes and worn-out shoes, drenched in sweat hacking at sugarcane plants twice my height, they don’t look the other way now. Instead, they provide me information related to sugarcane plantations and growing food profitably.

In my village, a lot of children are left in the lurch. They are in a very fragile emotional state and feel aloof and unsupported. I feel lonely as well, but I have my siblings to look after until they become adults.

When my parents were here, all I had to do was focus on my education, but now most of my time is spent on the field, taking care of my siblings, and managing household chores.

I do not have an option as the government is yet to reach out to us with any help.

Promises of aid are not likely to come

Since our parents died, we stay in our own house, and our maternal uncle, who has been declared our guardian, visits us occasionally.

I am told that the state government passed an order, under the Mukhya Mantri Bal Seva Yojana, which says orphans will get monthly assistance of 4,000 rupees ($53.73 USD).

However, boys who are less than ten years of age don’t qualify for this scheme. That means Veer and I are ineligible. Geeta is ruled out, too, because, technically, we have a guardian.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi says children who lost their parents to Covid-19 will get a corpus of one million rupees when they turn 18 ($13,432 USC), but our names are missing from the list of beneficiaries.

Sometimes I wonder, are we even visible? Losing both parents is not the same as losing one twice over. When my parents died, I lost my identity as someone’s son. I lost the family and friends only connected to me through them.

Losing my parents has been an incalculable, lasting blow.

I hope my parents are proud of me and how I raised my siblings.