Discovery of fossilized palms in India give insight into the formation of the Himalayan Mountains

My discovery confirms the Himalayas did not evolve to their current location; they emerged from the Tethys Ocean. These palms lived close to the shore when they became fossilized 20 million years ago. Their preserved lengths suggest a warm, humid atmosphere with dense forest vegetation, unlike today, where no vegetation exists at those high altitudes.

- 3 years ago

October 22, 2022

LADAKH, India ꟷ I left the capital city of Leh to stay in a southern village called Stok near the Himalayas. Every morning at 6 a.m., after eating breakfast, I set out on a quest to find fossils. Considering the potential wealth of treasure I could find, I hiked for seven to eight hours a day. I always asked God to set me upon something special.

On one of my hikes, I made the decision to rest underneath a rock. I felt drained to the bone and my skin burned. Suddenly, my eyes fixed upon something. I realized I found a huge, fossilized palm leaf. No record existed at that point of discovering such a significant fossil. I praised the Almighty, feeling lucky and happy, and immediately regained all my lost energy.

The discovery did not assert a theory. Rather, it proved a conclusion. The presence of a tree with palm leaves provided enough evidence that the area was an ocean 20 million years ago. This discovery, I realized, refuted earlier hypotheses of the British and Indian Geological Surveys. It changed everything we learned in class to that date about the Himalayan Mountains. I began to wonder if the Himalayan range even existed prior to 20 million years ago.

Groundwater expert makes his way deep into the Himalayas to find fossils

By trade, I am a groundwater expert. Since 1987, I have eagerly traveled to remote areas. I often encounter challenging geological formations, difficult terrain, and adverse weather conditions. My groundwater explorations have taken me from the highest battleground of Siachen to the second-coldest region on earth called Dras.

Read more stories about mountain structures throughout the world from Orato.

Yet, I eagerly voyage to these remote areas not only to look for groundwater, but to find fossils. Even in Ladakh, the highest and coldest mountain desert in the world, I go out exploring when I can.

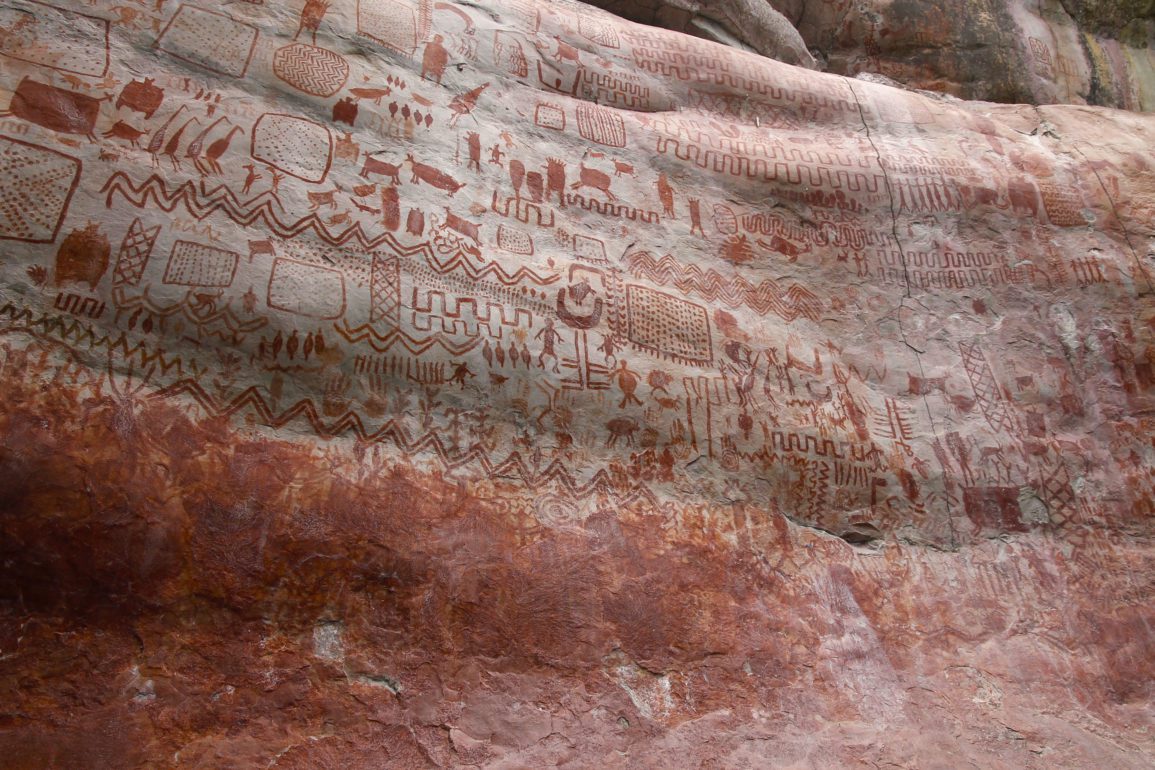

More recently I discovered 20-25 fossilized trees and palms. They date to the early Miocene era (a geological period dating from 18 to 23 million years ago). I found this paleo-channel deposit of fine to medium sandstone at 13,000 feet in Ladakh.

My discovery confirms the Himalayas did not evolve to their current location; they emerged from the Tethys Ocean. These palms lived close to the shore when they became fossilized 20 million years ago. Their preserved lengths suggest a warm, humid atmosphere with dense forest vegetation. This contrasts the modern atmosphere where no vegetation exists at those high altitudes.

Like me, others reported the presence of these 20-million-year-old fossils in Wakka. The Kargil fossils have been correlated with Kasauli fossils. In Kasauli, I found a few species like Garcinia, Gluta, and Combretum, which are extinct in the Himalayas. They are mainly found in Andaman Island, Malaysia, and Indonesia. Since Kasauli and Ladakh can be correlated, we can conclude the sediments of the Himalayas remained near the equator at deposition.

The scientific implications of discovering fossilized palms

For an entire tree to be fossilized, the sandstone had to be deposited at high energy. It suggests great energy removed the trees naturally – such as calamitous flash flooding that uprooted dense forests. When the system’s energy level declined, rivers transported the trees and dumped them in the canals.

Sand and muck also filled the channels, resulting in an anaerobic environment that preserved the plants and trees. Over time, when the sand turned into sandstone, these plants and trees became fossils.

Science further indicates the plants existed extremely close to the equator. Yet, we discovered them at a height of 13,000 feet above sea level. These trees and palms cannot live at high elevations in the summer or winter. So, the elevation had to be lower at the time.

The work of Alfred Wegner (founder of the continental drift hypothesis and plate tectonics) asserts that the Indian plate drifted like an island. Ninety million years ago, the plate drifted from a continent called Gondwanaland – modern day Africa, Antarctica, Australia, and South America.

It appears India floated like this for 70 million years, carrying dinosaurs and other species. Imagine that it acted as a large piece of construction equipment, moving earth and all the sediments in its path. Eventually, it slammed with enormous force into the Tibetan plate.

Read about the Paleontologist who discovered a new species of dinosaur in Argentina.

As far as we are aware, the prevailing view holds that the Himalayas were formed 50 million years ago. However, the discovery of fossils, palm trees, and other aquatic life forms in the modern cold mountain deserts of Ladakh suggest something else. The Himalayas are least 30 million years younger than previously believed and rose out of the ocean.

Global warming and flooding carried vegetation, community seeks to create geo-heritage sites

It appears the original height of my fossilized palm tree approached 50 to 60 feet. The process of fossilization must have occurred at an altitude no greater than 300-500 feet.

The fossils in Ladakh indisputably show they were deposited around the coast. The marine impact took place where plants were thriving, and sediments were being deposited. Since the fossils exhibit evidence of ocean influence, we can be sure the Himalayas were not yet a mountain range at the time these fossils were created.

The fossils also underline a period of global warming marked by flash floods that uprooted trees and devastated forests. Floods then carried and dumped the vegetation in river channels. The fossil evidence unequivocally indicates a geological time when the planet was warming. In addition to the trees and leaves, I have discovered several oyster sea fossils and other bivalve mollusk (invertebrates inside a hinged shell) in the lower Indus Molasse region.

Ms. Kunzang Dolma, president of Ladakh Geoparks, noted the importance of the fossils. She says they will help us understand our geological past. We want to see these areas preserved as geo-heritage sites. By doing so, we will encourage tourism to benefit the socioeconomic status of the community.

Next steps in theory evolution regarding the Himalayas

Moving forward, we hope to commission an in-depth analysis of these materials from the Birbal Sahni Institute of Palaeosciences (BSIP). The analysis will provide future generations with quick access to reference materials. Those studies will shed light on the development of plants and animals over geological time.

Reconstructing the paleoenvironment at the time of deposition will help put the full history of the evolution of the Himalayas in the appropriate perspective based on fossil evidence. This, in my opinion, will enable us to pinpoint the precise moment when the two tectonic plates clashed and actively constructed the mountains.

Much study needs to be done to prove the Himalayas did not emerge until 20 million years ago.