A glimpse into the crime-riddled world of greyhound dog racing: abuse runs rampant

Often, when confronted, these perpetrators recognize me from a previous visit where I gathered evidence. Frustration consumes them, and they often begin to threaten me, attempting to retrieve the dogs. When their anger erupts, they swear at us, flinging expletives, and we get a glimpse of how they treat their animals. If I pull out a camera at that moment, they grow more furious, but their words and actions only add to the evidence used in the complaint.

- 1 year ago

October 7, 2024

SANTIAGO, Chile ꟷ When I fostered my first greyhound, I immediately noticed the visible scars on her body and the look of utter terror in her eyes. Everything seemed to affect her deeply and she harbored a deep fear of people. Witnessing it, I truly came to question the practices people engaged in with these animals.

Living in Spain at that time, I learned as much as possible about these animals. When I returned home to Chile, I began advocating for greyhounds. At the time, no foundations or rescuers addressed the issue, marking the start of my fight for greyhounds in Chile.

Read more stories out of Chile at Orato World Media.

Man fosters his first greyhound, birthing years of activism

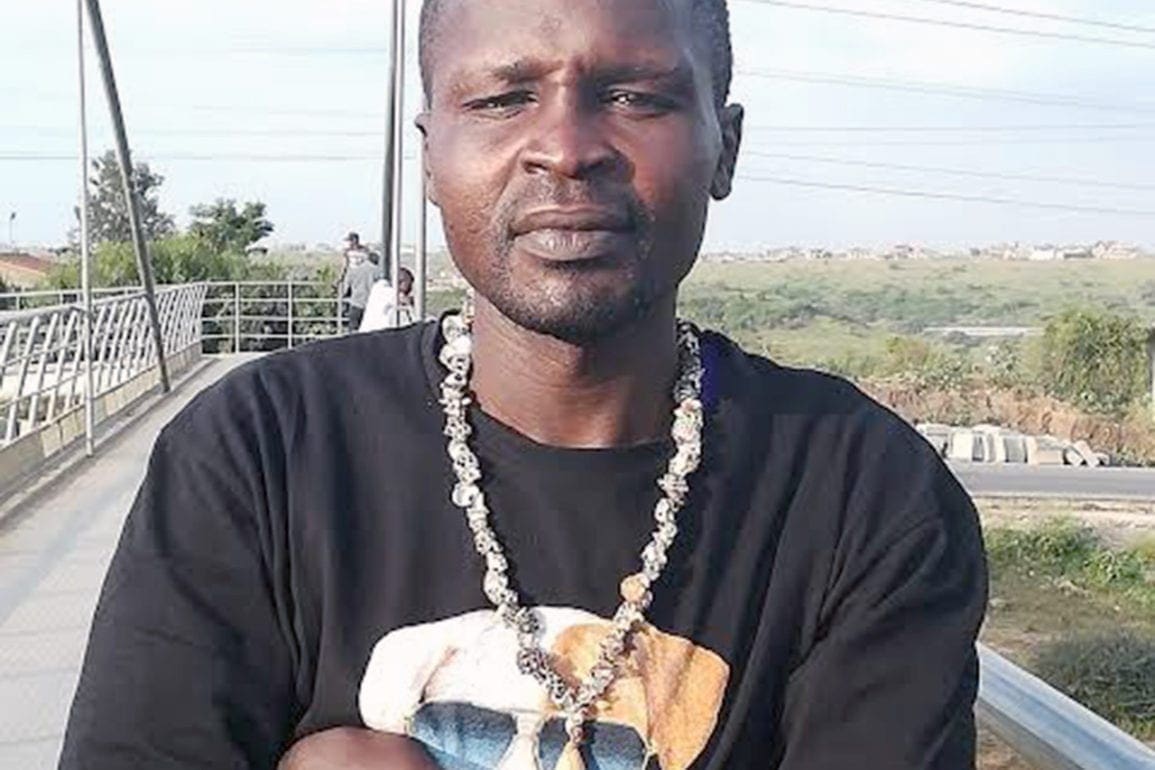

Thirteen years ago, while living in Europe, my journey into activism began. I left Chile at 18 years old after struggling for three years to find work. In Europe, I adopted Elvis, a French bulldog who remains with me today. A therapy dog, he remains naturally balanced emotionally. Elvis’ first best friend in Spain was a greyhound. One day, someone said, “Hey Luis, there’s a group called Galgo 112. They are looking for someone to foster greyhounds which they focus on rehabilitating.”

I thought, “Well, I’ll give it a try and see how things go.” Curious about Elvis’ reaction to having a greyhound in the house, I gave it a shot, becoming responsible for a foster dog’s recovery for the first time. People in Spain predominately use greyhounds for hunting, leading to a harrowing statistic. When hunting season ends, if the dog performed poorly or is deemed no longer useful, people abandon them to the tune of about 40,000 per year.

Back in Chile, I began to wonder if the dogs faced a similar fate. Did Chileans use greyhounds for hunting or perhaps for racing? Of course, the answer was yes and I rescued my first dog. The greyhound that landed in my care faced an atrocious disease, forcing us to euthanize him after two days.

I knew finding this dog in Lampa, near the capital city, meant something was going on. Yet, in general, no one talked about greyhounds, not even rescuers. In fact, I heard rescuers say the dogs proved too fast to be captured. These individuals believed greyhounds belonged in the countryside and lacked the qualities to be good pets. A stigma persisted around the breed.

Educating the public about greyhounds to break the stigma

Digging deeper, I discovered numerous dog tracks used for greyhound racing, and evidence of hunting as well. While adjusting back to life in Chile, I reached out to a woman named Pamela. She rescued greyhounds and was planning to start a foundation. In time, Pamela became the founder of the Fundación Galgos Chile. I had shared photos on Facebook of many greyhounds I helped rehabilitate in Spain, so, I made the connection and offered my support.

I lived near Providencia and Las Condes in the northeastern part of the capital city of Santiago. Greyhounds remained virtually unheard of in my community at that time. Nowadays, of course, they can be seen everywhere.

In our first rescue, I came upon an injured greyhound with a bony body. Neighbors were quick to criticize. “A greyhound in the city,” they exclaimed. “Are you out of your mind?” That stigma – that greyhounds belonged in the country – persisted. I began to educate people about cities in Spain like Barcelona, Madrid, and Valencia where greyhounds lived happily. All around Europe, in France and Germany, you often see greyhounds amongst urban populations.

Whether living on a big plot of land or in an apartment, people do not realize greyhounds commonly sleep up to 20 hours a day. As the citizens of the area began to better understand the dogs, inevitably, they asked, “Why are they so thin?” From there, our education phase took off.

Man enters the dangerous world of dog racing where crime runs rampant

It took three years for people to begin coming forward to help us locate the dog tracks in Chile – spaces essentially hidden from the public eye. Yet, no in-depth investigations existed. I formed my own team and we began pursuing independent investigations. As we rescued dogs who experienced severe exploitation, coming to us with broken bones, my anger flared. We needed to act quickly and file complaints to reach the culprits.

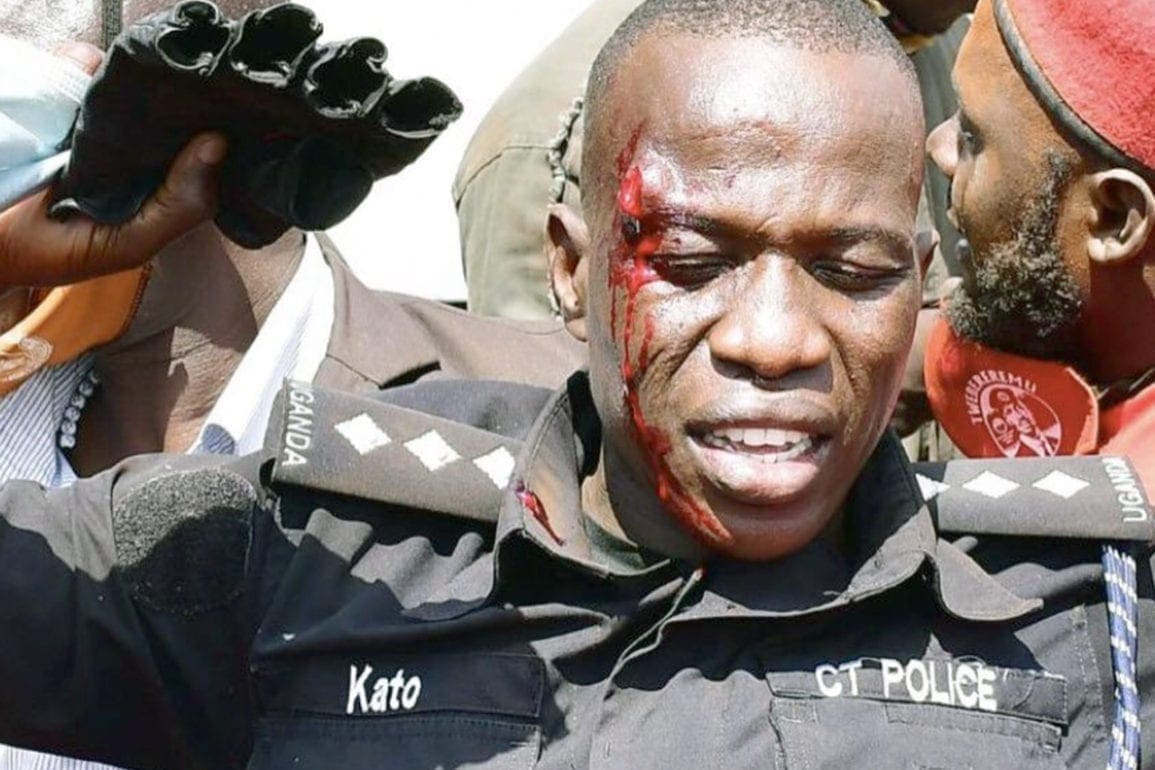

With each new complaint filed with the investigations police and Prosecutor’s Office, we handed over addresses and details of the number of dogs involved. In the process, I entered a dangerous world, exposing myself to threats. At the dog tracks, I discovered their handlers injecting them with all sorts of substances including stimulants. After the crowds cleared out, I found trash cans filled with used syringes and empty medication boxes.

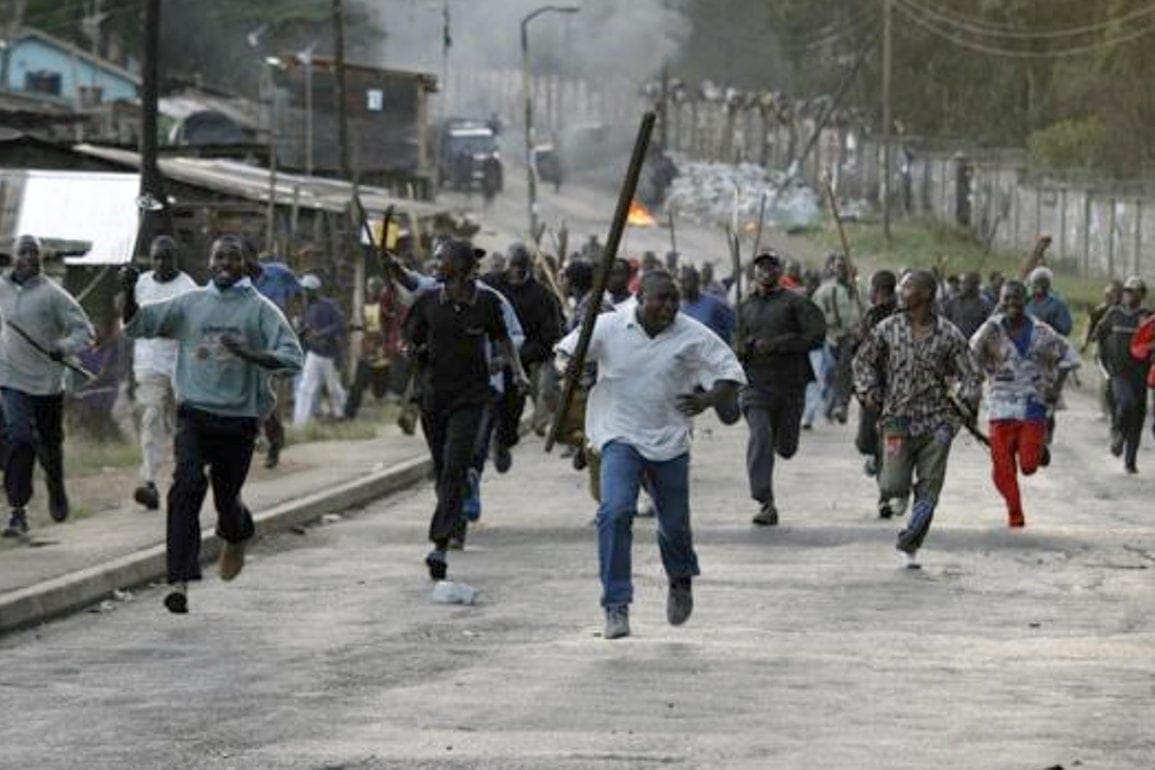

Illegal betting went from between 5,000 to 10,000 pesos, to massive sums, with drug trafficking now part of the mix. Today, that betting has skyrocketed into the millions at times. It felt like a free-for-all of illegal activity with no oversight. No municipal offices or state agencies monitored or regulated the races.

Commonly, animal exploitation becomes linked to other illicit activities and as we began reporting, many of the perpetrators had restraining orders on file for offenses like domestic violence or drug-related crimes. It took incredible courage on our team’s part to gather the evidence the authorities needed to act on.

At puppy mills, perpetrators erupt in anger and make threats

I soon began visiting sites selling puppies, asking for racing greyhounds. With my investigator hat on, I looked for signs of abuse. We documented cases of animals lacking proper food and water; or those revealing untreated wounds or injuries. Just taking a dog to race or hunt is not illegal. We needed to show solid evidence of things like malnourishment and physical harm.

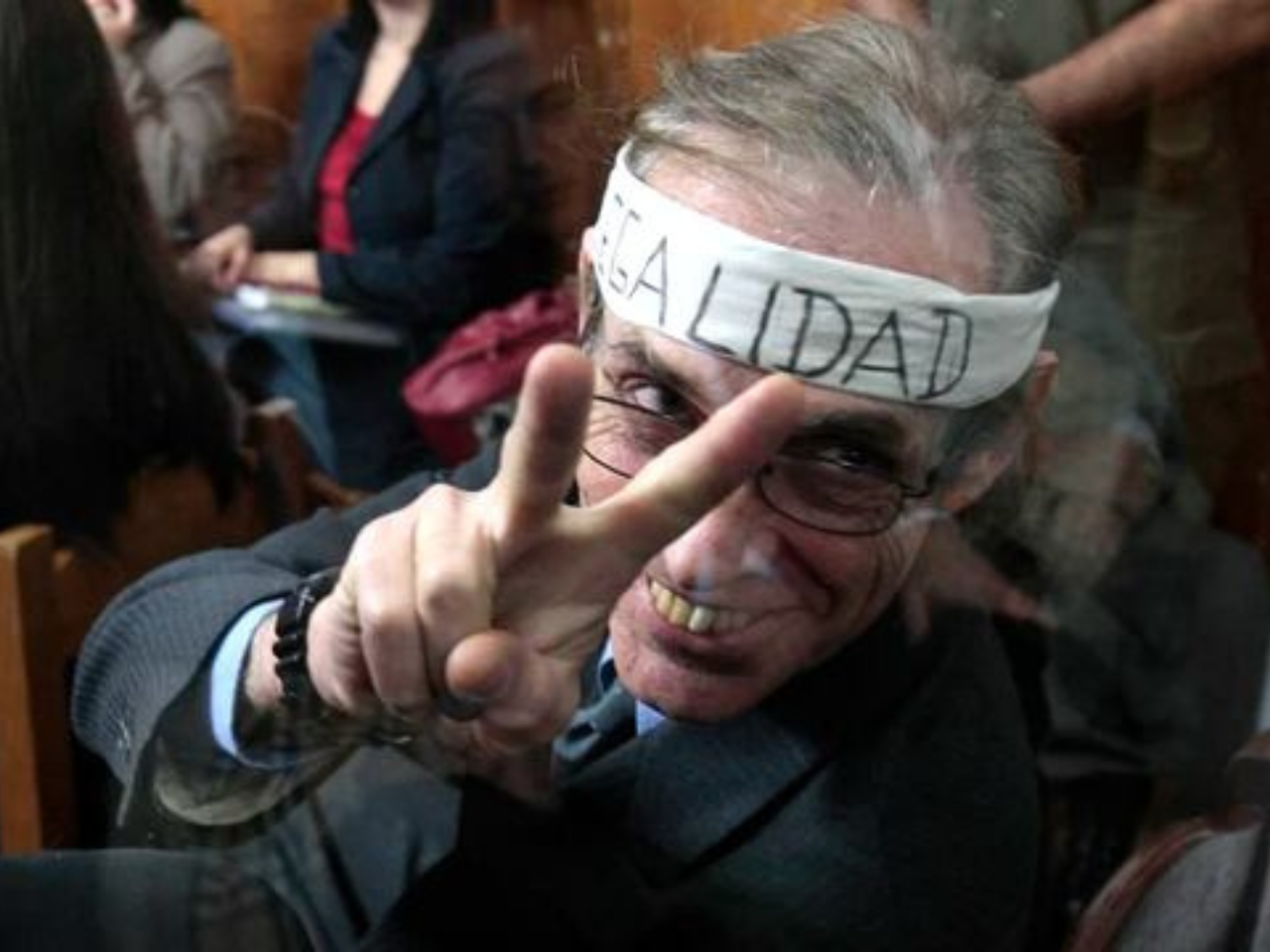

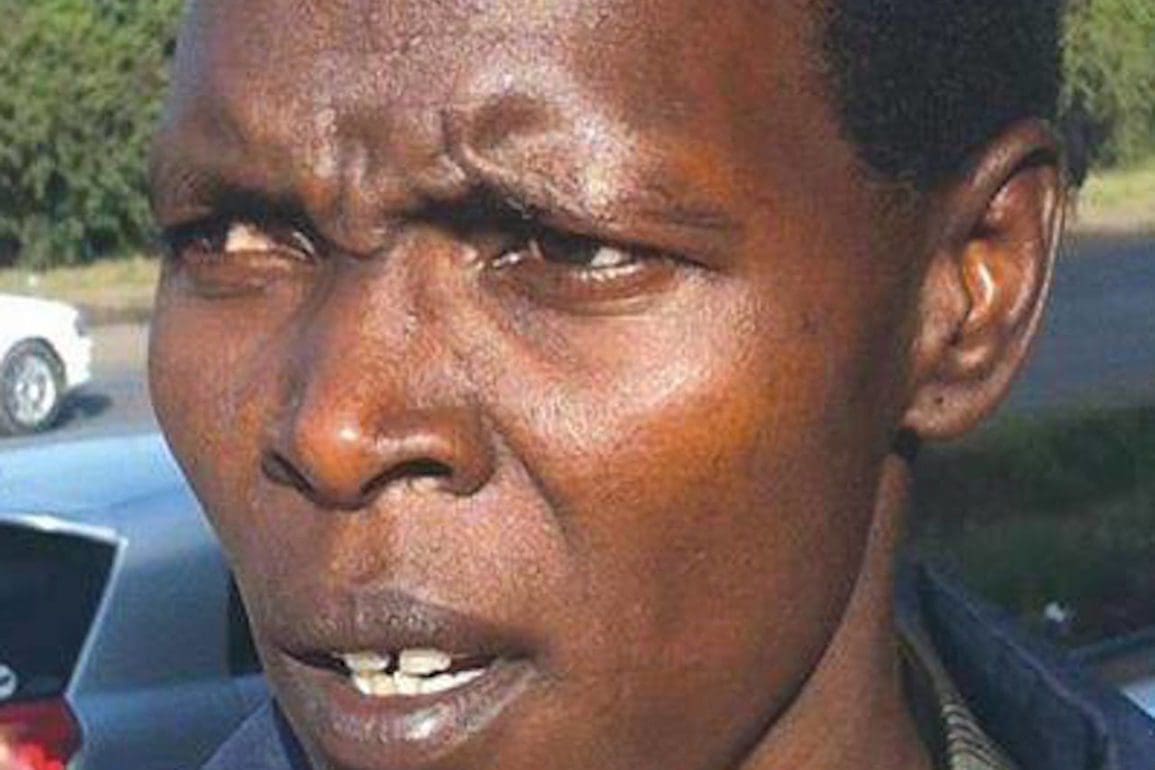

With enough evidence in hand, we worked with the police to carry out rescues, making sure to take all the dogs with us after going in. Predictably, the perpetrators insist the dogs are fine. They deny any abuse despite the clear, visible evidence. These individuals fail to see anything wrong with their actions. Often, when confronted, these perpetrators recognize me from a previous visit where I gathered evidence.

Frustration consumes them, and they often begin to threaten me, attempting to retrieve the dogs. When their anger erupts, they swear at us, flinging expletives, and we get a glimpse of how they treat their animals. If I pull out a camera at that moment, they grow more furious, but their words and actions only add to the evidence used in the complaint.

In Chile, rodeo is a tradition and an officially recognized sport. It has rules to follow. While the animals do suffer, they must abide by certain regulations and cameras exist during events. Greyhound racing remains neither recognized nor lawful in Chile. No regulation exists at all; no attention paid to how races are conducted. The industry operates in secrecy, rife with illicit trade, drug trafficking, animal smuggling, and abuse.

Promising greyhound puppies injected with stimulants and forced to run behind trucks

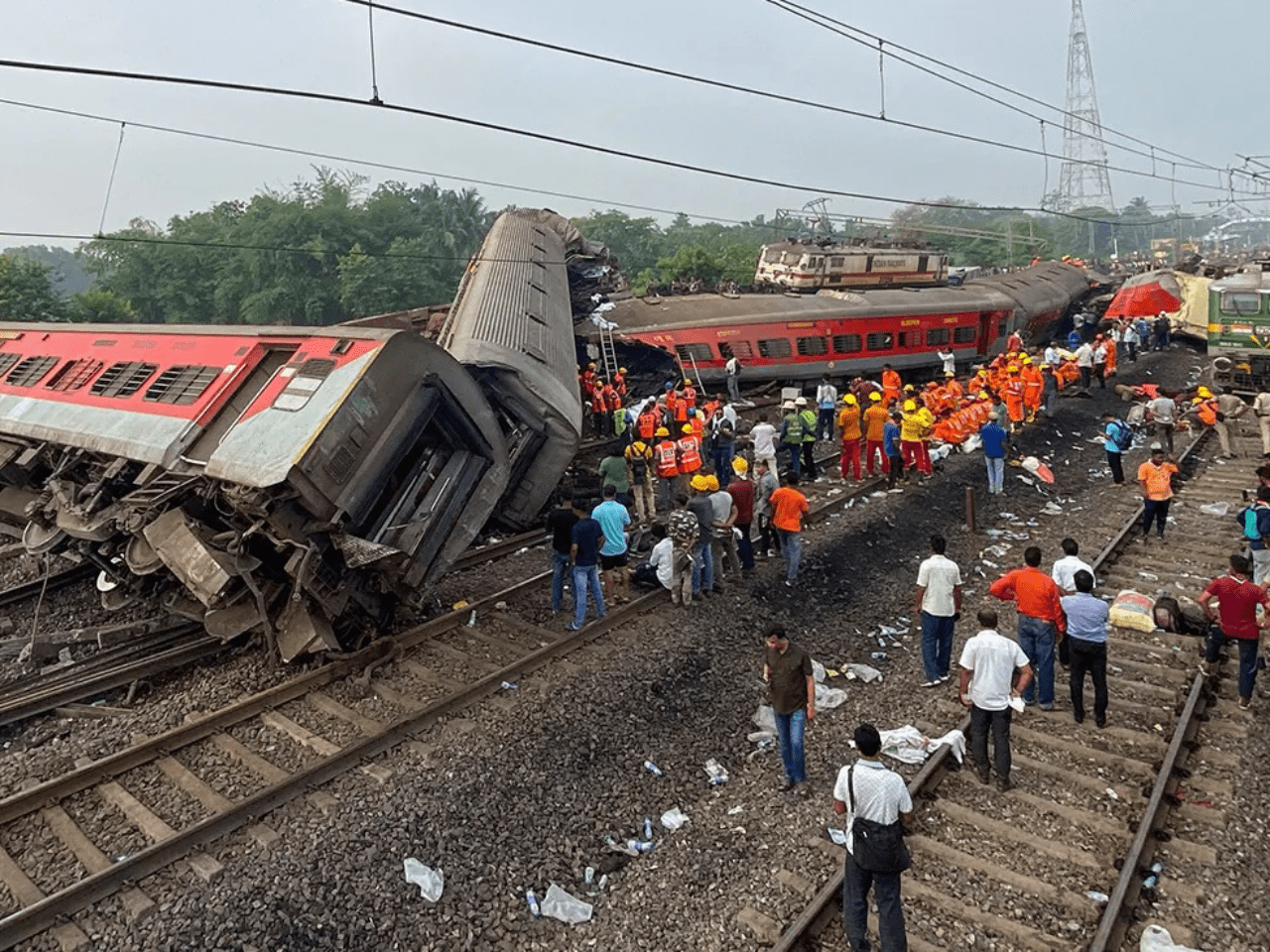

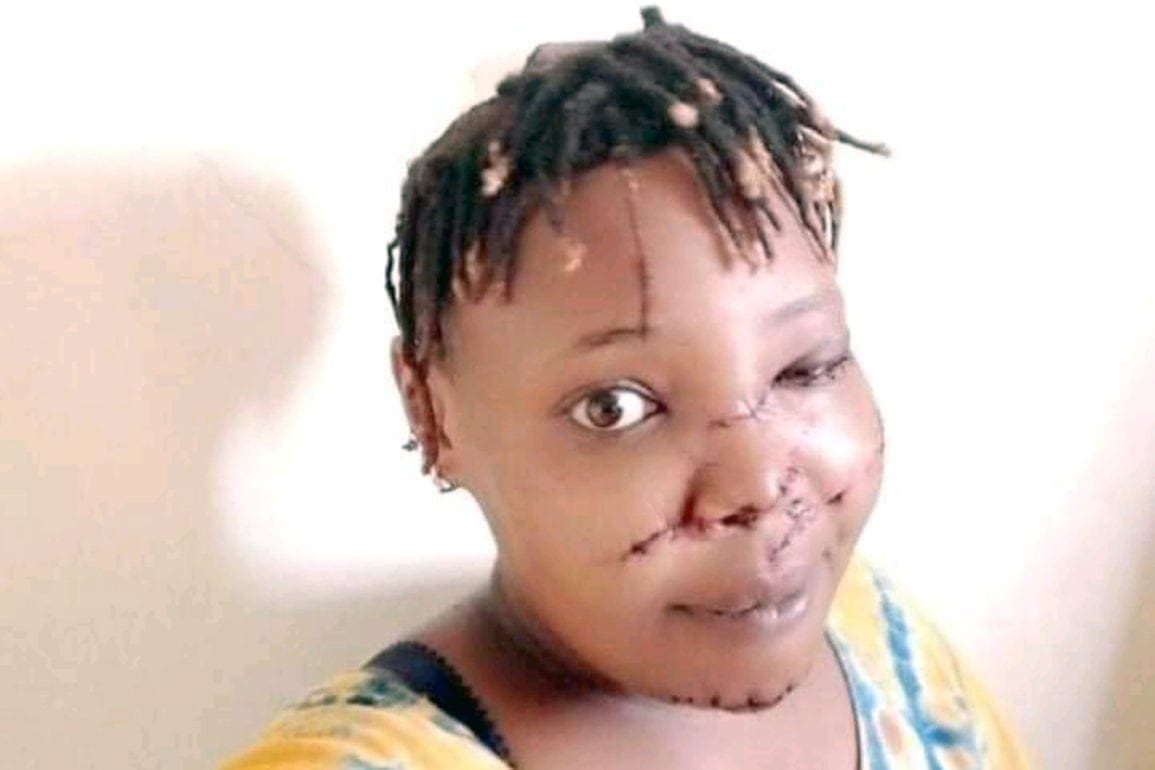

The races themselves take place in secretive places. When they release the dogs to start running, they risk awkward turns, hitting something in their path, breaking bones, or suffering other trauma. Some dogs lose their lives. To reach top speeds, the dogs undergo rigorous training on treadmills and dragging them behind trucks from a young age.

A retired champion or one from a long line of winners becomes a breeding dog. To breed her with another champion, if she seems unwilling, they engage in “assisted mating.” They often muzzle the female and force the process. When the litter of puppies emerges, they assess them to see which ones remain most suitable for racing by chasing rabbits. Those who fail are deemed useless and discarded.

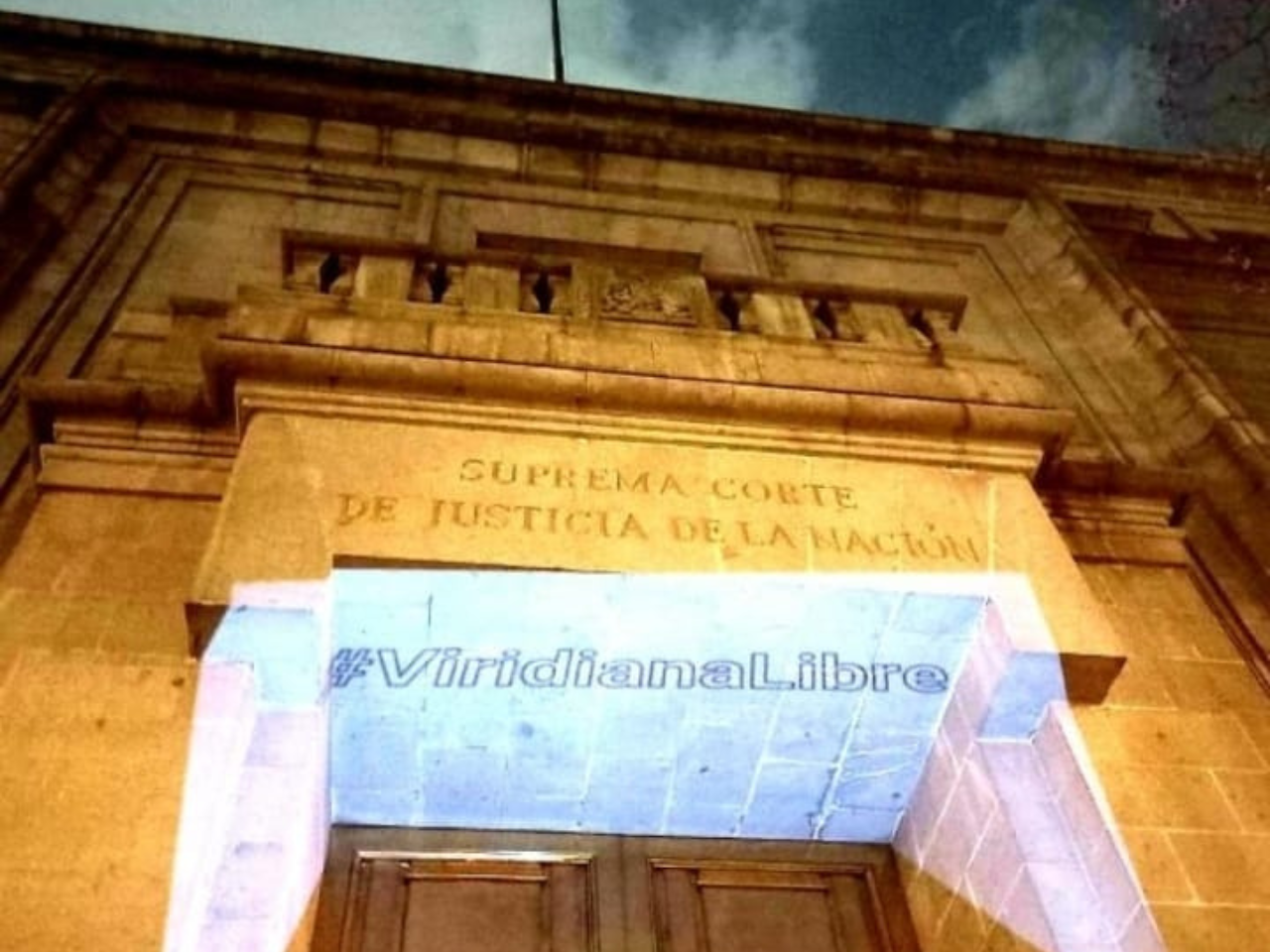

Promising puppies undergo intense training, racing up to the age of four or five before being retired. During those years, their handlers subject them to harmful substances, killing them from the inside. In Argentina, Uruguay, and parts of Brazil, they put an end to illegal greyhound racing, but not in Chile. In countries like England, Australia, and the United States, they legalized racing and built regulations, while shutting down illegal tracks.

We lobbied for a bill to ban dog racing with broad support from the Chilean public, but political considerations in the upcoming elections led to the bill’s rejection. Elected officials who opposed the bill represent rural areas. Some of those voting never visited a dog track and ignore the issue, while others remain aware. It takes time to open doors for new voices in government and successfully create change.

Activist argues against the legalization of greyhound racing entirely

Even with the best, most-regulated greyhound racetracks in the world, exploitation continues. The problem extends to gambling addictions while countless dogs continue to be abused and abandoned. Those responsible remain interested only in the dog who runs the fastest, wins the race, and brings in money, while regulation burden governments.

Often, decisions on total country-wide bans come after witnessing a rise in problems post-regulation, leading to a wealth of evidence that greyhound racing serves as a breeding ground for illegal activities. I call it state-funded exploitation.

In Chile, we hope the public votes for congressional candidates who support animal welfare in the upcoming elections. Advocating for animal protection in Congress traditionally faces significant challenges, but with new candidates, bills and proposals, combined with growing public interest, we feel the people want stronger protections now.

We need the candidates to embrace that call to action. Meanwhile, the state remains absent as some municipalities grant permits to run dog races. The evidence remains abundant. Greyhounds in Chile subjected to dog racing show clear signs of abuse, neglect, and drugging. Illegal betting runs rampant. We have the evidence of this mistreatment.