Makonde citizenship move cements status in Kenya

Shedding the refugee and immigrant labels afforded us new freedom and eradicated our fear.

- 5 years ago

June 15, 2021

MAPUTO, Mozambique — On Oct. 13, 2016, the Kenya Human Rights Commission led more than 600 Makonde people to the statehouse in the Capital of Nairobi to present a petition for our citizenship.

Nearly 1,200 miles away from our homeland of Mozambique, the president issued a decree: by year’s end, the Makonde people would be the 43rd tribe in Kenya.

The announcement changed our lives.

Shedding the refugee and immigrant labels afforded us new freedom and eradicated our fear.

Today I have a bank account. I have purchased a piece of land, and I can roam freely in my country.

Our children receive an education at the university and compete in the job market like any other Kenyan.

We have one of our own at the Kenya defense forces, eight serving in Kenyan prisons as wardens, one at the general service unit, and another in the Kenya Police.

The local communities have embraced us.

The journey from our homeland

Two generations ago, our grandfathers left Mozambique to the east African coast in search of work.

Instead, they took jobs with sisal farms owned by white settlers.

They mainly grew sisal fiber, traditionally used to make rope or twine.

In 1963 Kenya declared its independence from Britain, but our people continued as laborers at the plantations until the 1980s, when President Daniel Arap Moi took power.

Moi ordered all foreigners working in Kenya without legal documents and work permits to be deported or arrested and jailed.

Our grandfathers stopped working and scattered to various areas of the Kenyan coast. They knew if they stayed on the farms, they would be arrested.

Their ability to work and pay for their immigrant identity cards was stripped away.

The Digo people — who live between Mombasa and Tanga — secretly gave land to some of the Makonde people.

As a result, the Makonde were occasionally arrested but released upon paying a small bribe. The Digo also gave us sites to bury our dead.

More recently, I often encountered the police for doing business as a foreigner without papers.

Over time, the police became familiar with us, suggesting that we could bribe our way out of arrests if we had at least one dollar.

Four decades after Moi’s order, we finally have our citizenship.

It has meant so much to us that the president expressed his sorrow and apologized for taking so long to consider us their brothers and sisters.

Maintaining our history

Over the years, our children and grandchildren have intermarried with other Kenyan tribes, so it becomes difficult to tell who is from Mozambique.

I have never been to my homeland, and I don’t even know how to get there. I am Kenyan by definition, and my children are married by locals.

Yet, even after the second Makonde generation has settled in Kenya as immigrants, we have continued our ancestral culture.

The Makonde people are known for the art of wood carving.

Today we carve and sell our work on the beaches of Mombasa.

A few older community members continue to speak the Makonde language, and we practice our cultural rites of passage, such as circumcision.

They give our girls special lessons from their aunts about caring for the family and children.

Looking ahead

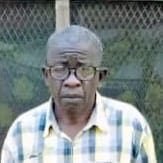

Today, I serve as the Chairman of the 3,764 Makonde people in Kenya.

My priority as a leader is to ensure the young generation is educated to position themselves well in the job market.

I am also educating my community on the basics of government processes such as birth registrations so that children can get into the systems and receive national identity cards.

I have continually told my community not to harbor the idea they are in a foreign country. Instead, the people must stand firm in their citizenship.

We have started a community-based group called The Makonde Development Organization, which serves as a vehicle for mobilization and voicing our concerns.

Today, the Makonde people can join the police service, vote, and freely participate in Kenya.

We are Kenyans, not Mozambicans, but that status did not come on a silver platter. We lived a life of agony and suffering for many years on the Kenyan coast.