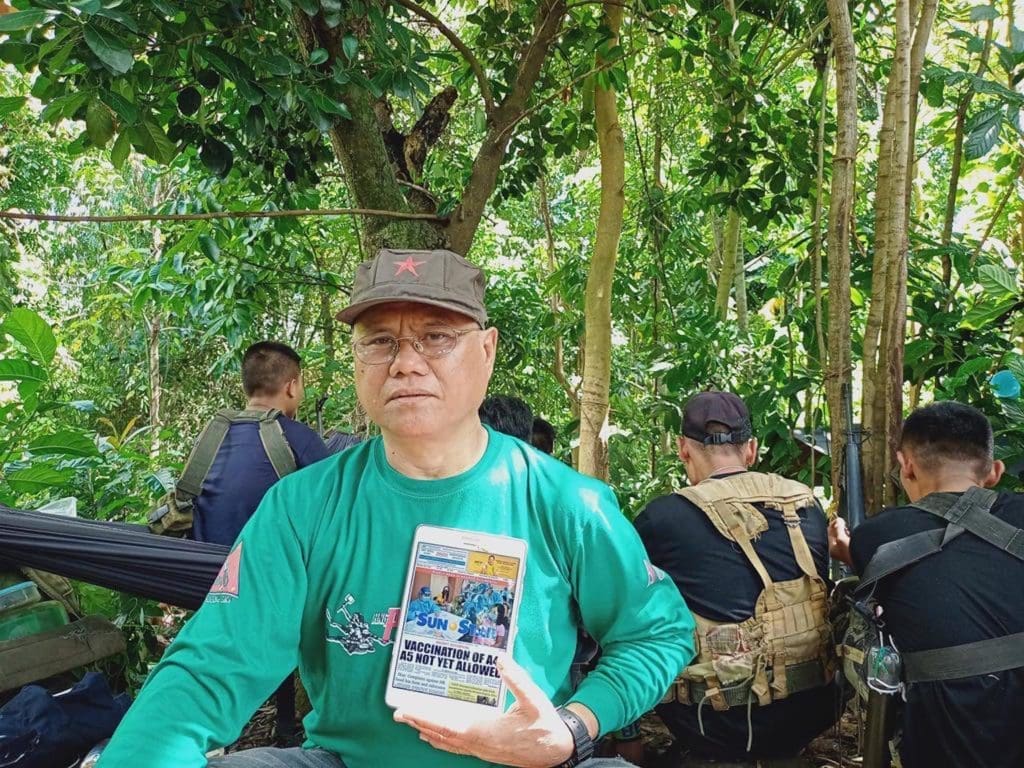

Philippines communist resistance fights deep in the jungle

Deep in the jungle of Negros Island, Philippines, a Communist insurgency marches on, 52 years into the guerilla war.

- 5 years ago

August 24, 2021

NEGROS ISLAND, Philippines — It was 2 a.m. on a memorable morning in 2004 when we launched a raid on the Philippine military’s militia, known as the Citizen Armed Force Geographical Unit (CAFGU).

CAFGU is an auxiliary army created to fight what the Philippine government calls insurgents. I am one of those insurgents.

Residents of Negros Island, where I’ve lived all my life, complained of CAFGU’s torture, illegal entry into their homes, and indiscriminate firing.

We heard the militia was selling drugs and stealing the locals’ water buffalo.

Our informants in the village where the CAFGU detachment was deployed had laid the groundwork for the raid.

The villagers told us how many soldiers were stationed there, what firearms they carried, and the placement of their huts and foxholes.

My brothers in arms snuck into the CAFGU base through the rear while I covered them from outside the building.

One small creak made CAFGU soldiers wise to our assault.

Gunfire rang out between us and the militia in the depths of darkness.

I don’t know if I killed anyone or not because I couldn’t see the enemy I was shooting at.

We had the element of surprise, and on that occasion, it was enough.

The CAFGU detachment fled into the night and abandoned their position in the village.

We took the weapons and equipment they left behind, saving them for the next battle.

I fight for the New People’s Army (NPA), the militant wing of the Communist Party of the Philippines.

Dreams crushed by poverty

I was born and raised in a coastal village, called a barangay, near Bacolod City, Negros Occidental.

When I was young, my family and I made our livelihood by selling locally-grown coffee and bibingka (baked rice cake).

My dream was to become an architect, but my family was too poor to send me to college.

I enlisted with the Philippine Navy and was stationed on the Mindanao island.

We transported soldiers from the Philippine Marines and Army battalions.

After three years, I left the Navy to become a merchant marine, but jobs were scarce.

I applied to numerous shipping companies, but I couldn’t land a single job in two years of searching for my new profession.

When I came back to my hometown, resistance was brewing against the government.

The US-Marcos dictatorship that ruled from 1965 to 1986 believed in “constitutional authoritarianism” and kept the country under martial law from 1972 until 1981.

Many of my barkada (close friends) were members of the Kabataang Makabayan or KM (Patriotic Youth).

We held local protests against the administration and through KM’s educational courses I began to learn the truth about my country.

The Philippines is a rich country in natural resources whose people are kept poor by U.S. imperialism, domestic feudalism, and bureaucrat capitalism.

Marcos was deposed in 1986 and I decided to become a full member of the NPA in 1994.

My parents and siblings didn’t approve of my decision because they were afraid I might get hurt.

My friends who knew I was a KM member weren’t surprised with my decision, while other friends were astounded when the news reached them that I went up to the mountains to fight with the NPA.

A rich country with an impoverished population

Negros Island is a vast agricultural land mainly populated with sugarcane plantations.

Most of the inhabitants (Negrosanon or Negrense) make a living in agriculture.

A handful of big landlords monopolize vast portions of the arable island area following massive corporate land grabs.

The impoverished farmers and farm workers depend on the will of these few landlords because they don’t have a path to land ownership.

Many of them receive wages ranging from PhP100 to PhP200 ($2-$4 USD) for eight hours of work. This is meager compared to the PhP395 ($7.90 USD) regional minimum wage for agriculture set by the government.

Negros Island residents who often protest for higher wages are met with violent police crackdowns.

The place I live is a seething volcano of social discontent that could erupt at any time.

When I entered the ranks of the NPA, I was assigned to a squad-sized armed propaganda unit responsible for growing our ranks.

We recruited locals for armed struggle by telling them they had a right to a decent living, just wages, benefits based on their work, and, most of all, their own land.

I would help organize the locals in demanding lower rent, abolishing predatory loans, and developing cooperative farming practices.

When that wouldn’t work, we’d seize the farmland by force.

I’m not a terrorist

But we don’t desire war for war’s sake.

We fight because of the injustices of destitute poverty that the bloated ruling class will never willfully address.

My hope is for genuine democracy to flourish in the Philippines and for peace based on social justice.

I reject the “terrorist organization” designation thrust upon the NPA by the West.

When the NPA executes someone, we only do it following conviction at a public trial.

We adhere to the International Law on Human Rights and Humanitarian Conduct in the civil war and the Comprehensive Agreement on Respect on Human Rights and International Humanitarian Law.

After 27 years of joining the NPA, I don’t have any regrets even though I was not able to achieve my dream of becoming an architect.