Scientists in Texas nominated for 2022 Nobel Peace Prize developed COVID-19 vaccine before Pandemic

Having already manufactured vaccines, we assumed it would be easy to garner support from investors, but no one wanted to fund us. I felt disappointed and helpless, knowing we could have slowed the spread of COVID-19 sooner. The funds never came, and the big manufacturers focused on implementing new technologies, leaving those already developed aside.

- 3 years ago

November 10, 2022

TEXAS, United States ꟷ In 2010, my research partner Peter J. Hotez and I began searching for a technology to fight the coronavirus. Although there had been some outbreaks, no one had laid eyes on the virus nor imagined a full pandemic could originate from it. We published our studies without a patent, focused more on equity for countries in need.

When everyone began searching for ways to control the COVID-19 Pandemic, we already had a solution. Little by little, people around the world became aware of our patent-free research. Once the media discovered the story and news about it spread, my colleague Peter and I earned the nomination for the Nobel Peace Prize.

COVID-19 research developed long before Pandemic, remained ignored

I grew up in the countryside of Honduras, surrounded by birds chirping in the early morning, and the noise of vehicles traveling across city roads. My family managed cattle farms on the eastern side of the country and my father worked in the capital.

Read more stories from Orato World Media about the COVID-19 Pandemic.

At an early age, I learned to ride horses and bathe in rivers. I saw the differences in opportunity between people in rural and urban areas; and witnessed poverty, limited access to education, and poor health conditions. All these inequities influenced my life and work.

At the Vaccine Development Center at Texas Children’s Hospital, I sought to fill these gaps by finding cures for diseases affecting those in poverty and lack of healthcare. We focused on developing vaccines for internal parasites and the Chagas Disease.

Read more stories out of Honduras from Orato World Media.

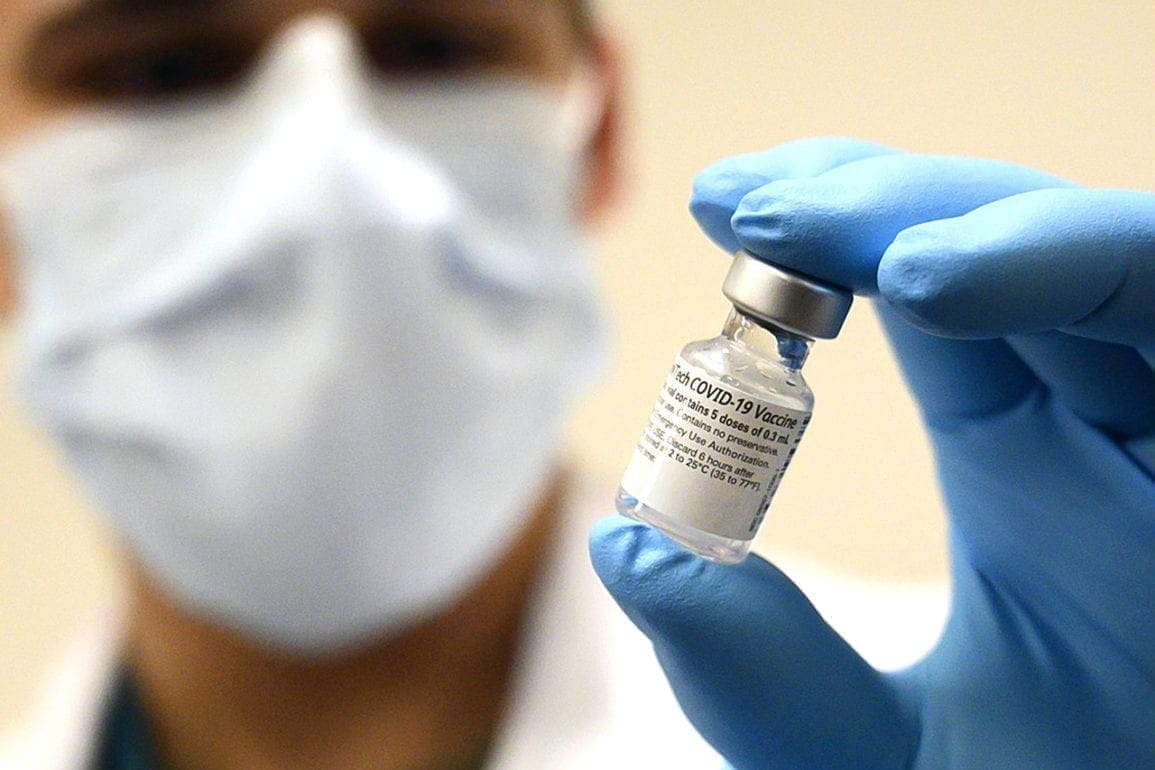

When we learned about the coronavirus [long before the Pandemic], no multinationals appeared interested in researching a cure, so we adopted the disease and built consortiums. When the COVID-19 Pandemic began, we had a solution to offer. We could use the same values from our research during the pandemic – offering an open science modality and collaborating with countries facing inequity to develop and produce vaccines. We targeted countries with an ecosystem of manufacturers and a population in need.

Having already manufactured vaccines, we assumed it would be easy to garner support from investors, but no one wanted to fund us. I felt disappointed and helpless, knowing we could have slowed the spread of COVID-19 sooner. The funds never came, and the big manufacturers focused on implementing new technologies, leaving those already developed aside. Fortunately, for the good of humanity, they succeeded. However, it took longer.

Nobel Peace Prize nomination recognizes early COVID-19 research

The delays in distributing vaccines caused panic. I remember hearing that some people doubted and did not understand the vaccine. They even asserted the shots came from aliens. Meanwhile, our published research remained available. Anyone who read it could create vaccines, and many did. Other countries called us to collaborate.

When Peter and I received the 2022 nomination for the Nobel Peace Prize, along with our work team, my heart filled with pure joy. I felt so proud to be recognized for our efforts in creating a low-cost, patent-free COVID-19 vaccine. Beyond the personal satisfaction, I knew the achievement would serve to empower and bring attention to my home country of Honduras.

I held back tears and my heartbeat quickened as I imagined a brighter future. Sometimes, coming from a smaller country, we can feel like less, but my achievement illustrates that borders remain irrelevant to what we can do.

Not everyone can say I was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize – and that nomination serves as a gift in my life. Though I ultimately did not win, I feel no disappointment. On the contrary, I celebrate because many people benefited from our work.

The most important thing of all is to see how science and education remain essential for populations to live in prosperity. When a person remains healthy, they become productive, experience more job opportunities, and enjoy greater happiness and creativity.

Joyful communities experience less chance of conflict and even war. Health can lead to peace.