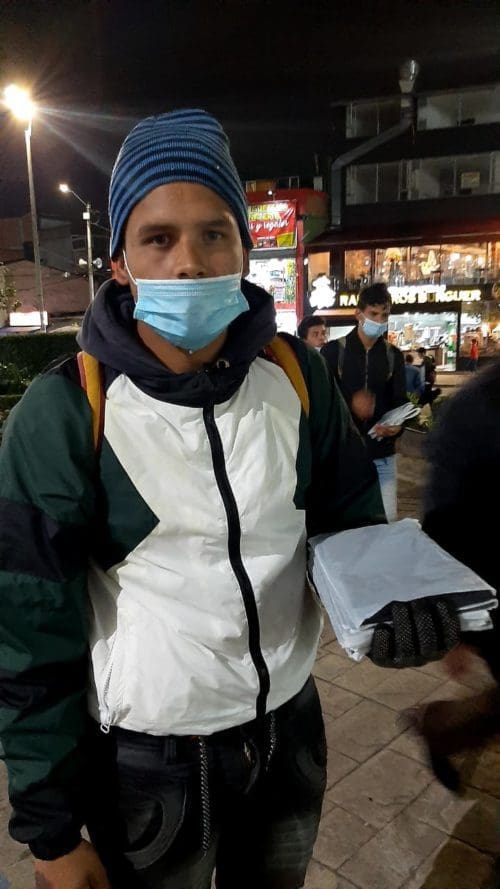

Venezuelan refugee walks over 500 miles for freedom; left hopeless

Many Venezuelan migrants have travelled to Colombia seeking new opportunities, however, the lack of employment and the conditions of some governments have not allowed all immigrants to survive.

- 5 years ago

July 12, 2021

BOGATÁ, Colombia – I left Caracas, Venezuela by foot six years ago. I arrived in Colombia full of hopes and dreams but from the beginning, it has been brutal.

For the first 17 days, I lived on the streets and I only drank water. I have not slept or eaten well. I thought migrating would be easier.

Every day, I wish I could return to my homeland. People made me believe that I could have a better life outside my country. That promise never came true.

False promises for migrants left in poverty

Given the conditions in Venezuela, I decided to leave the country. It seemed like the best option to get out of the crisis.

My friends, who had already left, said that it was a dream come true; they said they were living in paradise. They encouraged me to take the journey.

The border was eight hours from Maracaibo or 14 hours from San Cristóbal. I made the walk with no money. Venezuelans who set out on foot throughout South America are called “walkers”. I believed it was my only option and I was determined to get to Maicao.

I decided to pack my backpack and take the trip with a couple of friends.

My acquaintances told me that there was employment, food, and a better quality of life in Colombia.

It took me 17 days to get to the border. Without rest, in the sun and rain, I became hungry and thirsty. Pain ravaged my feet, but my goal remained intact. I was determined to leave my country. The walk was incredibly strenuous, but I’m a young man and overcame the journey.

I passed across the border with a group of migrants without much of a problem. Once in Colombia, I spent seven months in Riohacha, a city on the country’s northern side where the Ranchería River meets the Caribbean Sea.

It is known for its native Wayúu people.

There, I slept on the street. I was cold and did not have food to eat. I began to realize that the dream was not as wonderful as I told myself it would be. No one helped me and I had to scour for food in the garbage to survive.

Wandering and hunger become a way of life

I thought, if I wanted to have a future, I should relocate to a bigger city so I continued to walk to Cartagena. Again, I faced difficulty. I slept for a long time on the beach. It saddens me to remember.

I went through many difficult moments throughout my journey. People denied me a plate of food, gave me nasty looks, and kicked me out of places when I begged.

Soon, I left Cartagena and arrived in Bogotá. I was alone but had high hopes I could get ahead. I was still a dreamer. My little ones, my wife, and my family back home pushed me to continue.

Soon, I came to understand that people deceived me, and I even deceived myself. They sold me on the premise that Venezuelans were welcoming to migrants, but what I experienced was different.

The photos I had seen on social media were just for appearances.

I was looking forward to bringing my beautiful family here but I’ve had to work hard just to survive. In Venezuela, I have been a wanderer. I learned that nothing in life is easy; that to have something, you have to work hard for it.

Migrants find ways to earn a meager living

Becoming a recycler in Bogota was a new beginning for me. It allowed me to bring my siblings here and they helped with the work, so it was less stressful on me. Eventually, we managed to bring my parents, wife, and children.

After a few months, when we were all together, we had to redouble our efforts.

I stopped working as a recycler and was determined to be a street vendor. I still don’t know if it was a good idea; the results have not met expectations. Our daily goal for earnings is 35,000 pesos (approximately $9.33 USD) to guarantee us a plate of food.

On the streets, some vendors are very good, and some are very bad. Our challenge is that there are eleven of us at home.

In the mornings, a friend gives me breakfast and I pay for it in the evening. At lunch, I pick up a soup, or I wait to get home to eat. At home, we can only buy chicken giblets with rice. There are too many of us to afford the luxuries of meat or chicken.

My job is to stop every day outside a shopping center to sell bags. Naturally, I feel the contempt from the public. I see the sour faces and hear their answers and insults, but it allows me to have a few coins at the end of the day.

No hope for a future leads to dreams of going home

I haven’t had the opportunity to study. My Venezuelan identity card was stolen to make matters worse, and I don’t receive benefits from the Colombian government. I am an illegal.

It is doubtful I will achieve my dream of obtaining a decent job. I don’t want to sell bags my whole life. What I need is a steady job where I can work hard. I long to be able to eat a hamburger, buy clothes, travel, and to give my children what I never had in 26 years.

Every day I sell less and spend more. The pandemic made our situation worse. I will continue working in the streets, but my heart will always be in Venezuela.

I hope to return home one day.