Two interpreters for British Armed Forces trapped in Kabul

They risked their lives as interpreters for the British Armed Forces in their home of Afghanistan. Now the UK is gone, the Taliban have taken over, and they’re lives are in danger.

- 5 years ago

August 18, 2021

KABUL, Afghanistan — My name is Ezatullah Jabarkhil Ahmadgull and I was a British Armed Forces interpreter from 2011 to 2013. Now I am trapped in Taliban-controlled Kabul.

For the past two months, I’ve been waiting on the UK government to approve my application for entry into the country, something they promised me when I enlisted.

I was shocked when I saw on TV the Taliban had seized Kabul on Sunday, August 15, 2021.

My family and I relocated to the capital eight years ago from Lashkar Gah, in the south of the country, because the Taliban were threatening my father.

They told him our whole family would be massacred if I didn’t quit working for the British Armed Forces.

We’ve worked as masons in Kabul since 2013, living in relative peace.

Now, I can’t leave my home or feed my wife and daughter.

The Taliban know who I am, and I’ll be killed on-site if they recognize me.

Staying at home isn’t a long-term option for me either, we’ll starve if I don’t get back to work.

My life is in greater danger now than it was when I served on the frontline during the NATO invasion of my country.

Lost British soldier

On one mission, we heard a British Armed Forces member got lost outside Lashkar Gah and was taken hostage by the Taliban.

I spoke to the locals in the area to find out about his last known whereabouts and detail any eyewitness accounts.

My information led us to find the soldier on the same day he’d gone missing. Tragically, he’d been left executed in a ditch when we reached his location. His parents would have a body to bury, at the very least.

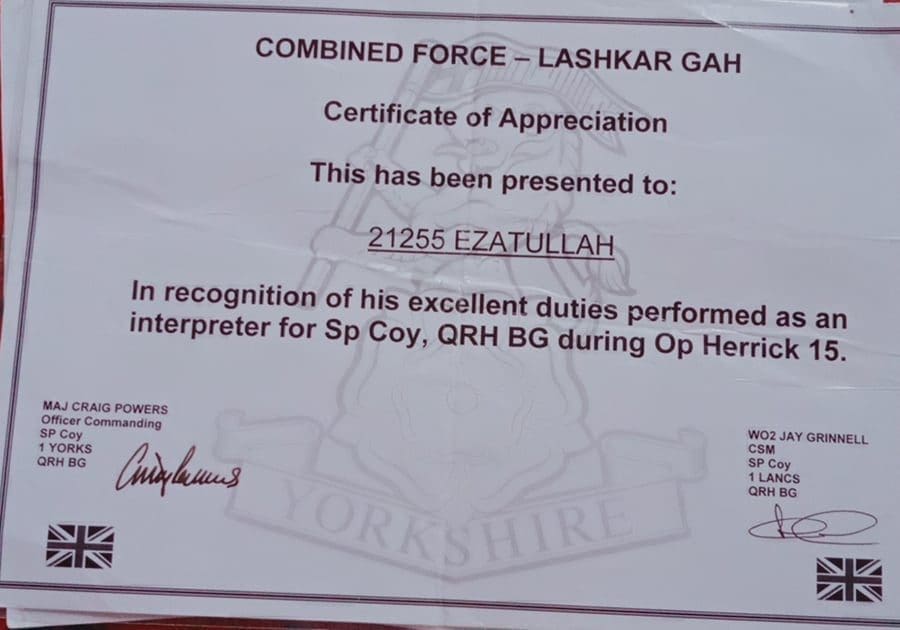

I received two certificates of appreciation from the British Armed Forces for my work, one in which I was recognized for excellence.

The men in my battalion were like brothers to me, but I’ve been left behind.

Other interpreters who had the same job as me have been accepted to the UK, but for the past two months, I’ve been stuck in limbo.

I did my job, now it’s time for the UK to hold up their end of the bargain.

Noor Hassan Shinwari, British Armed Forces interpreter

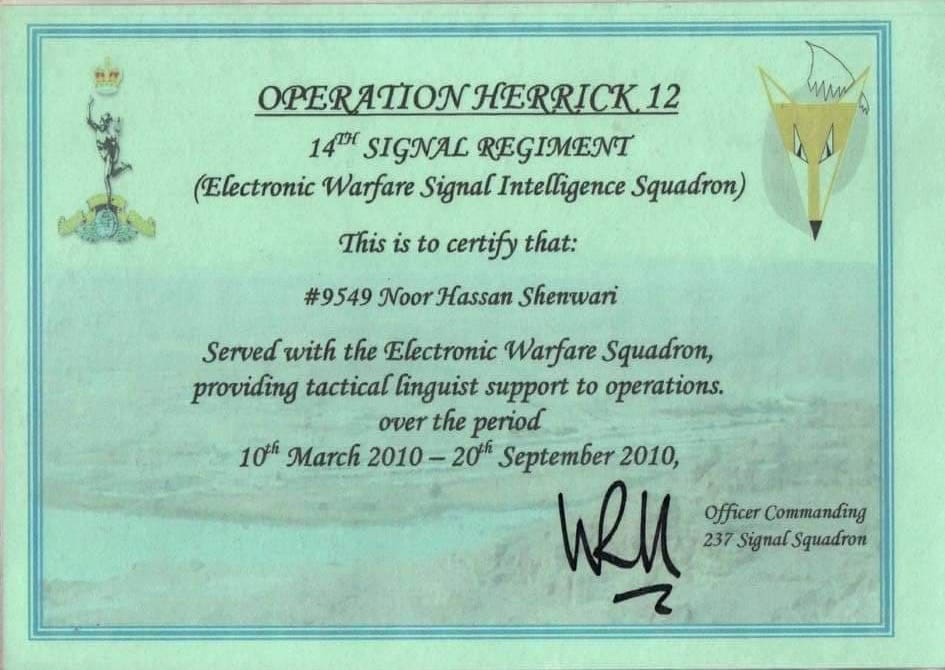

KABUL, Afghanistan — My name is Noor Hassan Shinwari. I was a British Armed Forces interpreter in Helmand, Afghanistan from September 2009 to August 2010, and I was deemed ineligible for resettlement in the UK.

Now I’m trapped in Kabul, unable to leave my home, with my four daughters and one son.

If I need groceries, I send my nine-year-old daughter to pick them up. Selling car parts out of my home is currently my only source of income.

Since the Taliban took over the city on Sunday, August 15, 2021, I’ve stayed in hiding at home, fearing for my life.

I’m a shopkeeper here in the capital and when my brother called me on Sunday to say the Taliban had taken over, I laughed at the possibility.

There’s no way the Taliban could have taken over Kabul, I said, they’re fighting out in the mountains. Then I saw the Afghan flag descend down a pole at a roundabout near my shop and the Taliban banner hoisted up in its place.

I closed up shop and ran home, where I’ve stayed hunkered down ever since.

When the Taliban last seized power in 1996, my family and I fled to Pakistan, where I learned English. We happily returned following the 2001 NATO invasion, but jobs were scarce.

The British Armed Forces were one of the few places that called me in for an interview when I returned to my home country. In 2008, I got my first job assisting the NATO mission.

For one and a half years, I was an Assistant Supervisor for an American petrol company called Red Star Enterprises Limited, refueling NATO aircraft at Bagram International Airport. It wasn’t until September 2009, that I was brought to the frontline.

Intercepting on the frontline

The Helmand province, where I was deployed with the 14th Signal Regiment (Electronic Warfare Signal Intelligence Squadron), saw some of the fiercest fighting in Afghanistan.

We were out on patrol, driving down roads, not knowing if an Improvised Explosive Device would blow our convoy to pieces.

The technicians in our vehicle listened for Taliban radio chatter. Suddenly, we intercepted a radio dispatch and I heard the unmistakable planning of an attack.

“They see us,” and “They’re planning an ambush,” I told the officers in our vehicle. Without the element of surprise, the Taliban didn’t stand a chance against the British Armed Forces on that day.

When I wasn’t working, I’d get phone calls from the Taliban threatening to kill me and my family if I didn’t quit my job.

My father was abducted and beaten; they only kept him alive so he could pass along the same threat to me.

In October 2010, I resigned as an interpreter to protect my family, and my brother, also an interpreter for the British Armed Forces, did the same.

We moved to Kabul in 2019, in search of a more peaceful life and I opened a shop. All I want is peace in Afghanistan, but that doesn’t seem possible anymore. My only choice now is to seek amnesty in the UK.

On June 25, 2021, the British Ministry of Defence informed me I was ineligible for resettlement because I was dismissed from the British Armed Forces. I wasn’t fired, I resigned.

Even more bizarrely, my brother has been approved for resettlement in the UK, despite working the same job as me and also resigning.

All I can do now is send letters to the Ministry of Defense in protest and speak to the media, hoping there is a way out.

Bashir (pseudonym), dentist

KABUL, Afghanistan — On Sunday, August 15, 2021, I was in the basement of my aunt’s laundromat when I started getting calls from family members.

The reception wasn’t very good, so I went upstairs. That was when I first heard the Taliban had taken Kabul.

Not a moment later, I saw Taliban fighters on motorbikes zoom down the street through the laundromat window.

My sister wasn’t wearing the Taliban-approved hijab and she immediately became my priority. We rushed home together to keep her safe from the new authorities.

Thankfully, I had worn traditional clothing that day and we made it safely back to our house.

I wasn’t expecting the city to fall so suddenly, I’d hoped for at least five months more freedom. My first emotion was fear, not for myself, but for the women in my family.

Our house has become crowded with family members seeking refuge under our roof. The women haven’t left the home and aren’t planning to.

Taliban fighters have become a regular sight on the street since Sunday. I saw four of them guarding a checkpoint on my street and one of them sleeping.

The Taliban inside Kabul right now were here before the government lost the rest of the country, and they came out of hiding when the capital was surrounded. The city was seized by terrorists hiding in plain sight.

The only government police and soldiers I saw were fleeing to the city center in groups of five, some of them in uniform, others changing clothes as they fled.

There must have been about 400 to 500 of them running away, who knows where to.

The only gunfire I’ve heard is the Taliban shooting into the air out of celebration. Kabul went down without a fight.

Don’t normalize the Taliban

There’s an attempt by our new overlords to normalize what’s happening right now, but most shops are closed and the streets are relatively empty. You rarely see women anywhere anymore.

The dentist office where I work has been closed since the takeover and I’m left indefinitely without any source of income.

New Taliban restrictions mean women and men can’t work in the same departments, which has resulted in all the women in Helmand’s banks losing their jobs.

In universities, male teachers can only teach male students, and women teachers face uncertainty about the future of any education for women.

People working in the medical profession like myself will need to wear traditional clothing.

The Taliban have offered a reprieve to government workers, to get them back into offices. My father works in the Foreign Ministry and is sure he’ll be replaced by an extremist stooge.

It is my belief this all happened because of corruption in the military, government, and a hurried U.S. withdrawal.

The military lied to the government about how many soldiers it had, and the government lied to the military saying they had struck a peace deal with the Taliban, even as Taliban fighters surprised and overpowered the Afghan military.

Our only option now is to try and adjust to our current reality.

When I saw people fleeing to the Kabul airport, trying to board a plane, and falling to their death, I felt immense sorrow. I don’t blame my countrymen for trying to flee.

That’s not an option for me though, I have a family here. I’ll stay in Afghanistan, through thick and thin.