On 40-year anniversary of the Falklands War, ex-combatant shares his story

We endured low temperatures with snow and rain for two months while sheltering outdoors. For sustenance, we drank water from the puddles and tried to melt snow in the sun; we hardly ate, as the meager food provided was terrible in quality.

- 4 years ago

May 10, 2022

BUENOS AIRES, Argentina—It was 1982, and I was nearly finished with my mandatory military service for Argentina. I had just 10 days left.

One of those days, I was on guard duty, and I began to see cars honking their horns and waving the Argentine flag. When I finished my shift, I asked my replacement what happened; “They took the Malvinas [Falkland Islands],” he said. Little did I know that announcement would change my life.

When I met up with other conscripts, they were discussing the event; one, bitterly disappointed, said with this new development, there was no way they would discharge us as scheduled. I still didn’t really understand what was happening.

Soon after, the authorities sent us to another regiment in Argentina for equipment; when we returned a week later, we found fellow conscripts who had been recently discharged but then called up again. Right there, they cut our hair for enlistment into the Army.

Family visits for conscripts occurred on the weekends. On one such day shortly after the haircuts, groups began to disrupt the visits with no explanation, taking us away and readying us to leave. The relatives waved from a distance, but I couldn’t see my own among the crowd.

Sent away to serve a country at war

They took us to a military airport and put us on a plane. The three-hour flight left us in windy and cold Río Gallegos, a city in Argentina’s far south. Around 4 a.m. we took another flight, this one loaded onto a plane with no seats.

That trip was terrifying; everything jostled, rolled and fell all over within the plane, and we jolted our way through an extremely violent landing. It felt like a delirium.

A commander spoke to us during the flight, saying it was an honor to have us on the plane since they were taking us to the Malvinas to fight for the country. I still didn’t know what was going on.

Around 11 a.m., we arrived in Stanley, the capital port city of the Malvinas. We immediately got orders to march 20 kilometers (12.4 miles) into a headwind bearing heavy equipment.

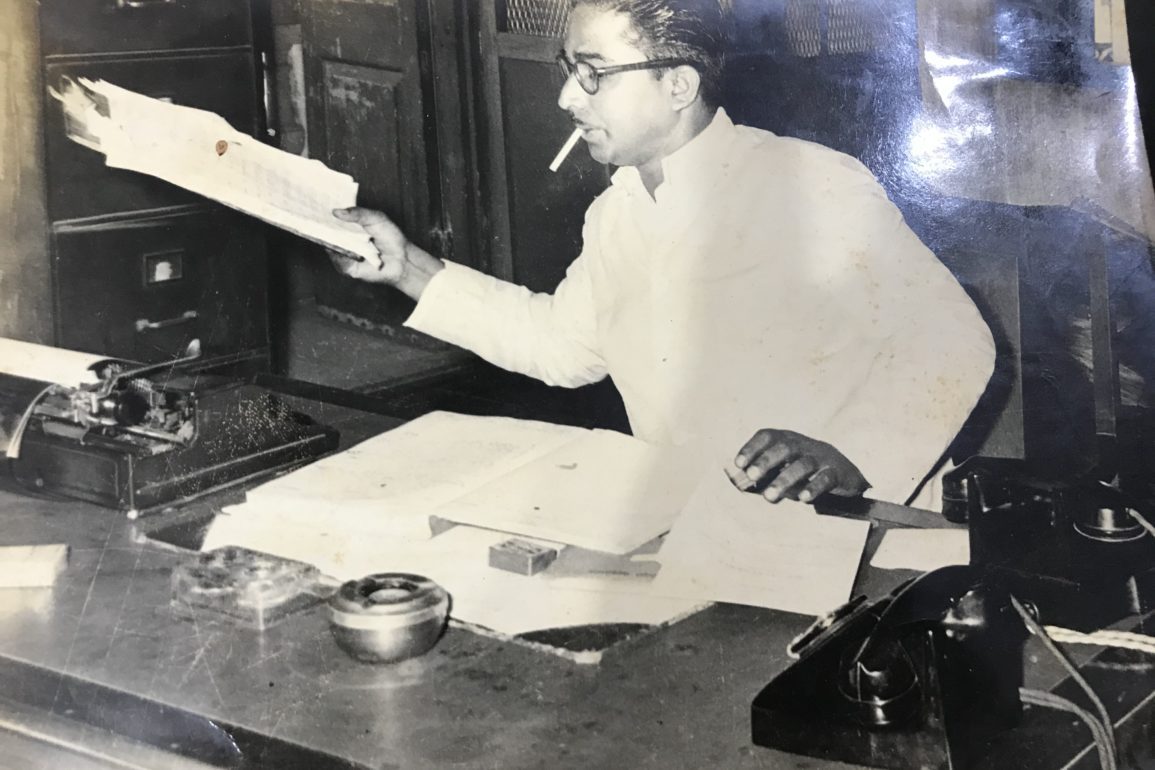

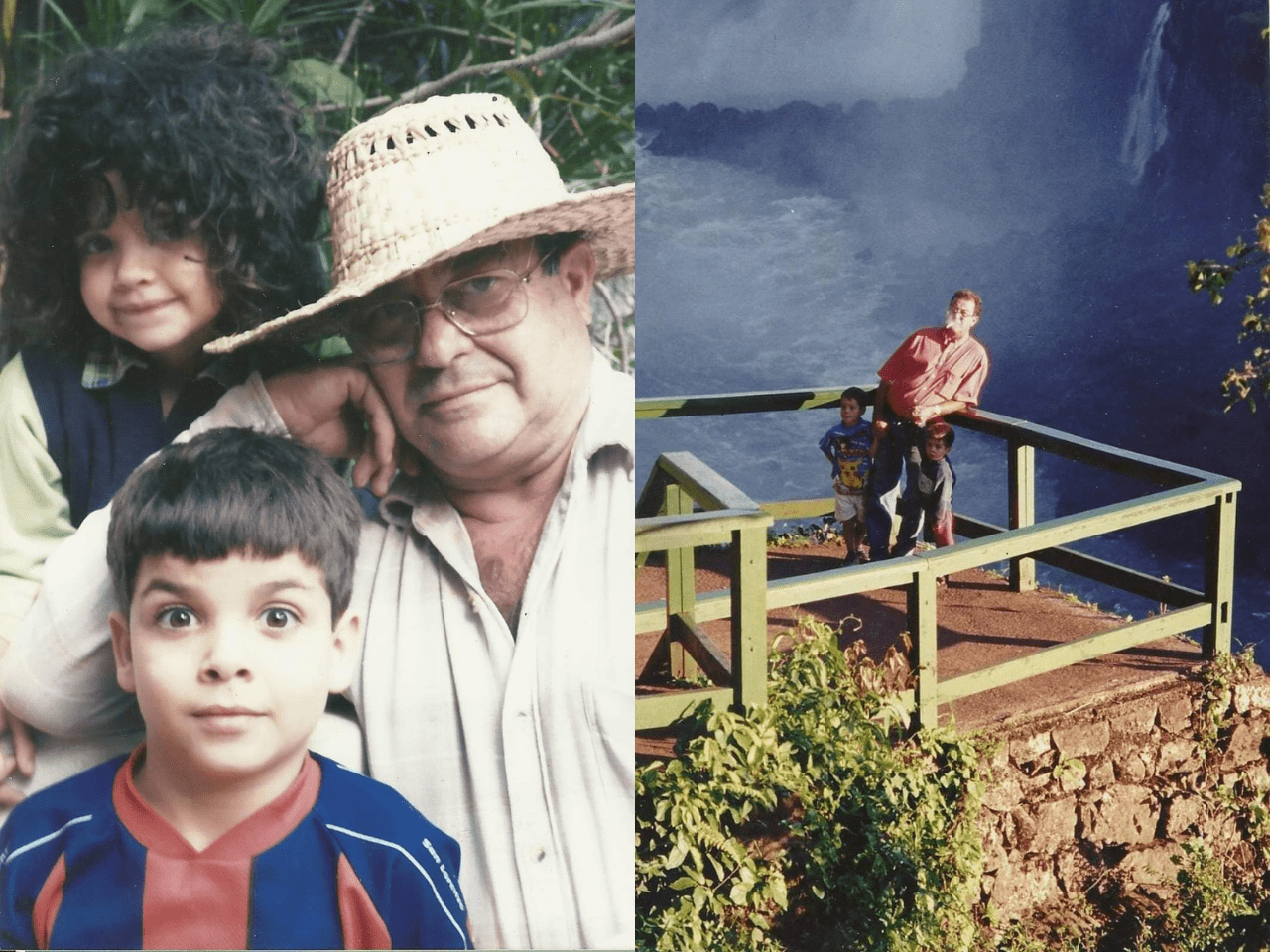

When we arrived at our destination, I saw a man pass by, all dressed in orange and with a camera. I thought he was a gringo, so I started insulting him until he told me he was Argentine. I asked him to take our photo, and he took it and left; we continued our way to the trench.

Meanwhile, the regiment never gave official news about our departure to the Malvinas to our families. My family actually found out what had happened to me through that photo I had requested of the stranger in orange; it ended up running in a popular newspaper.

My father and brothers saw the photo, but they didn’t want to tell my mother to keep her from worrying. She did eventually find out.

Two months of war, then returned as POWs to Argentina

It was hard to accept my new reality. The first days were fine until the war started, but I had had a very bad time in the military service already—they punished me several times because I escaped or misbehaved, and those punishments had given me pneumonia. I wanted it to end as soon as possible, but there was no escaping from the Malvinas; because it is an island, it was like a prison.

As for the war itself, I was lucky because my equipment worked well and I was well prepared physically. However, some of my fellow soldiers had nothing at all. We endured low temperatures with snow and rain for two months while sheltering outdoors. For sustenance, we drank water from the puddles and tried to melt snow in the sun; we hardly ate, as the meager food provided was terrible in quality.

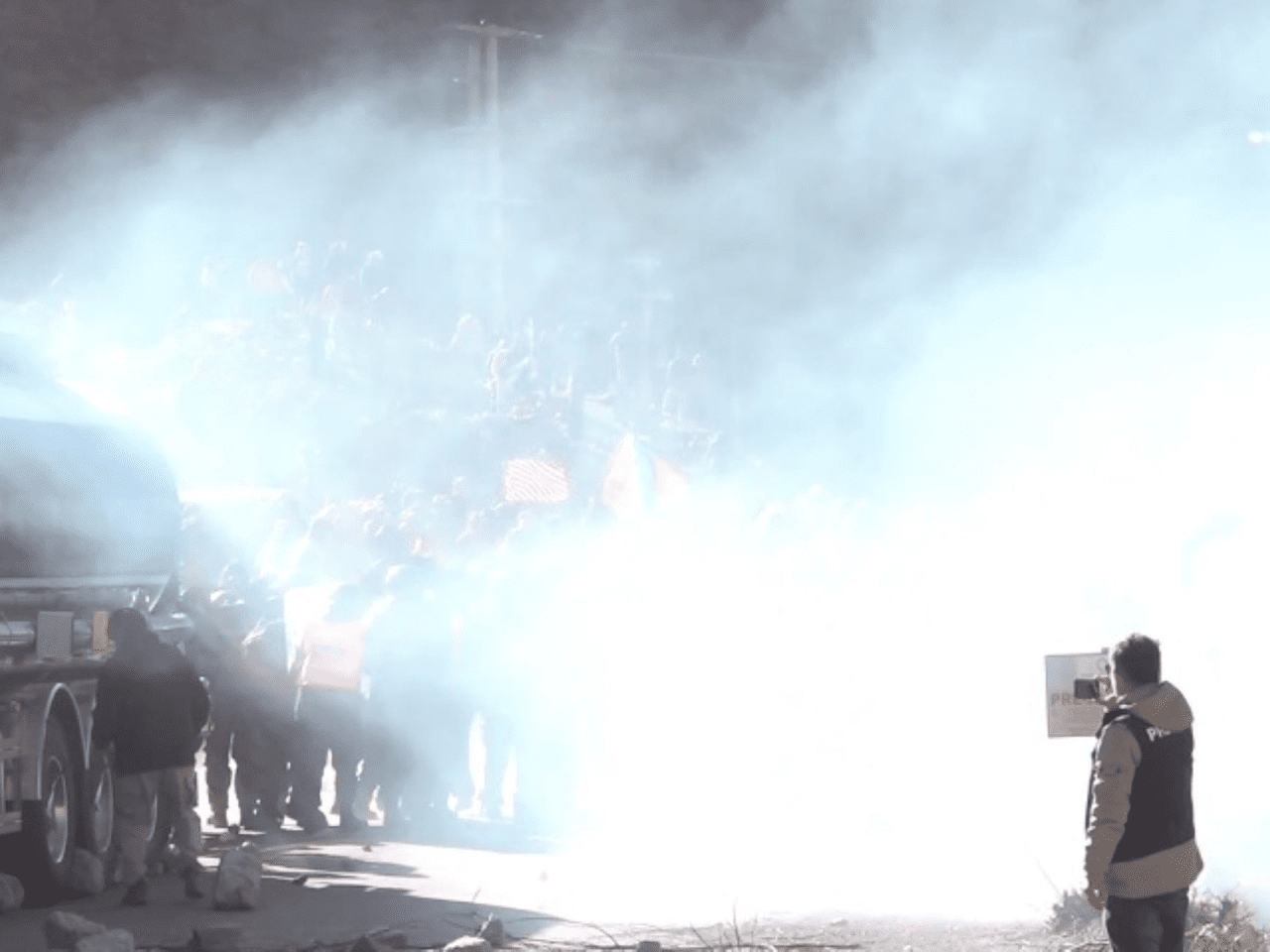

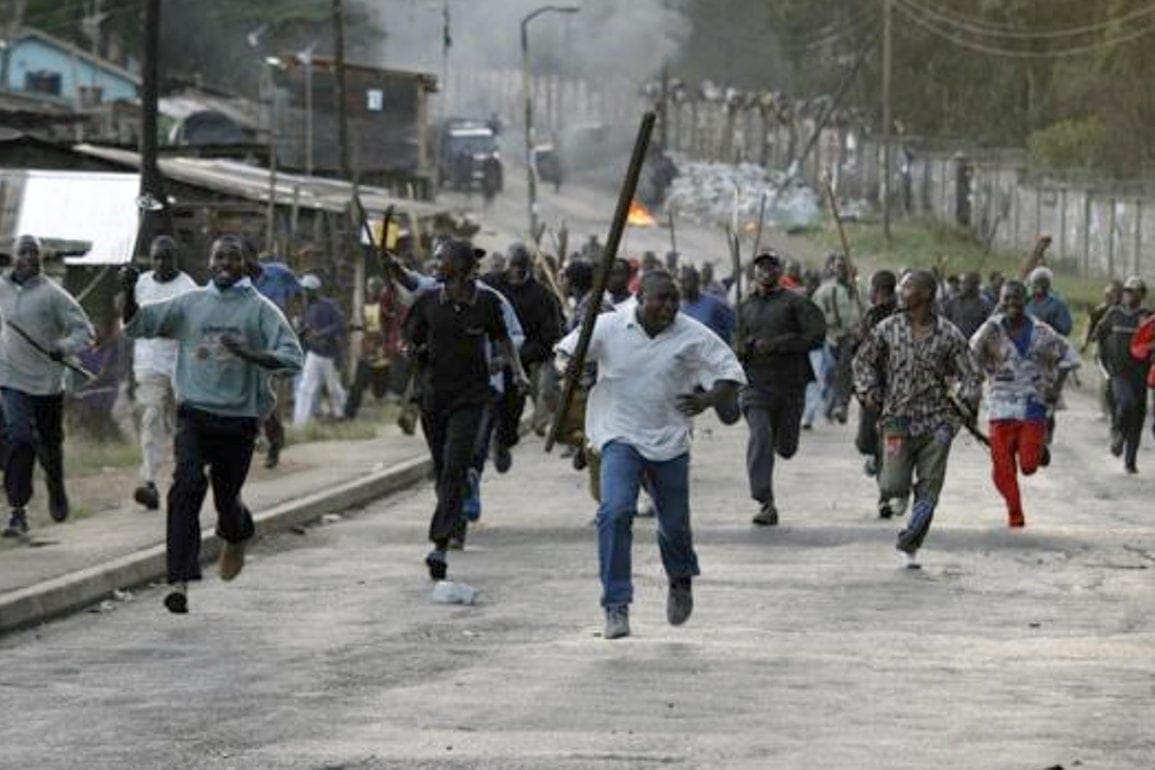

The final fight lasted nine hours, first with a bombardment and then with shooting at us. Finally, the enemy took me prisoner and took me to the post office, where I spent the night.

The next day an Englishman came, told us that he was in charge of us, and asked us who were professional military soldiers versus civilian soldiers like me. Nobody said anything—they were afraid that they would be shot—but the civilian soldiers began to point them out. The Englishman grabbed them to sweep the place.

At this point, I hadn’t eaten for three days. I ran into English soldiers who were looking for food to cook, but I just wanted cookies and sweet potatoes, I helped them with their search and grabbed what I could for myself, including some wine. When I returned to my place, I ate, had a bottle of wine to myself, and passed out until the next day.

To free us and return us to Argentina, our captors took us on a raft in the open sea to the SS Canberra ocean liner. To access the huge ship, we had to climb a rope ladder up its side. I tried not to look down because I thought I was going to fall. I was so afraid of dying; in fact, I felt like I was going to die the entire time at some stage.

Return to civilian life proves challenging

Returning to normal life was tough. When we first arrived at the Campo de Mayo military base in Buenos Aires, they asked us to write letters to our family. However, we were fed up and just wanted to go home. They switched gears and carried out so-called psychological studies where they asked us about our personal information, family data and everything about what we did in the war.

Truth is, it was the intelligence service who asked us the questions; they did not care about our mental health. In fact, they suggested that we forget what happened and not talk about it.

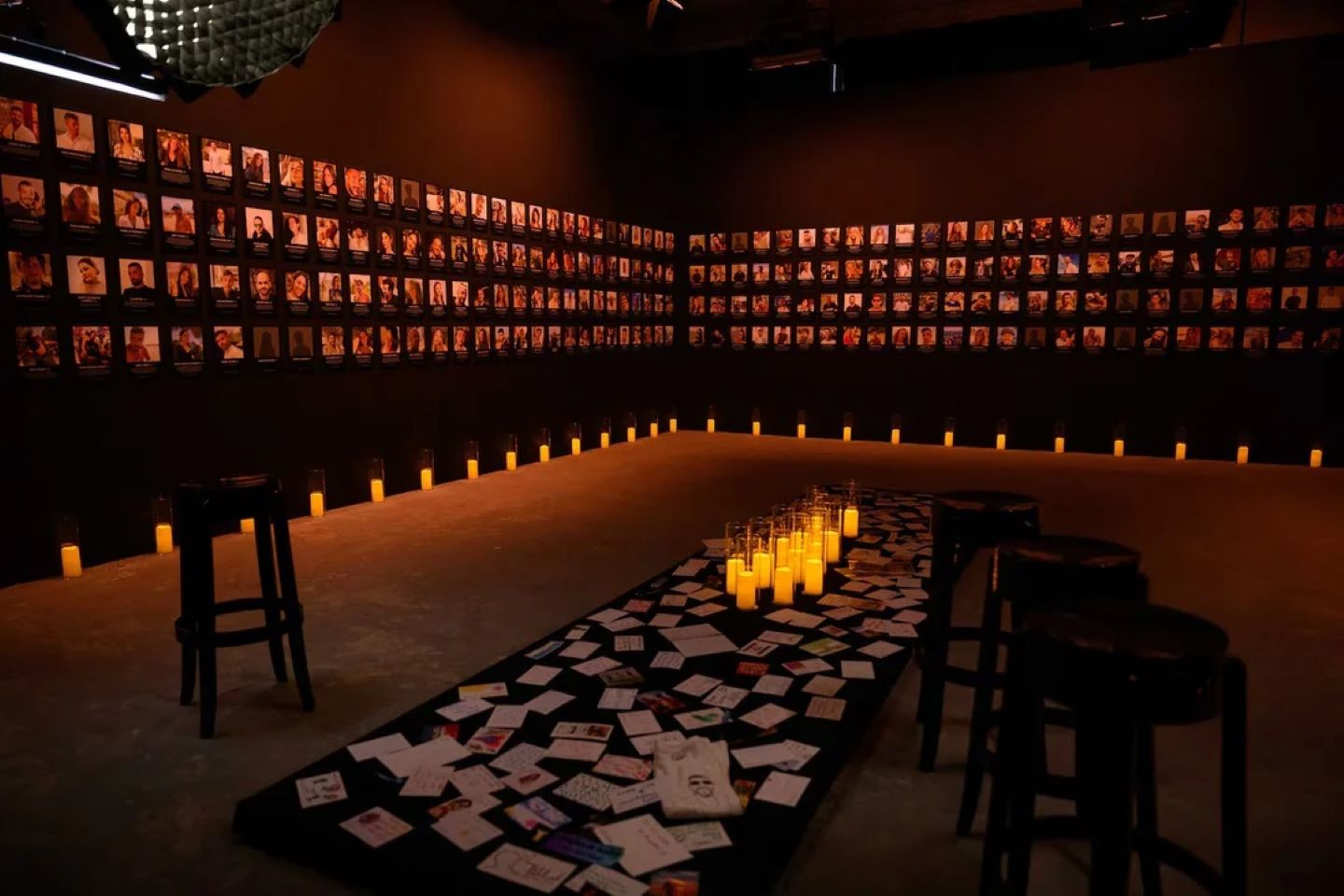

The first ten years after returning were very hard; some comrades took their own lives, and others ended up in prison. The best cases were able to study and get a degree, but those were the minority.

When we came back, we didn’t have jobs and nobody wanted to give us one. That’s when we began to organize ourselves and look for guidance in laws from other countries that provide economic and health protection to ex-soldiers.

We were able to make progress, but we had to fight hard and not everyone got their portion right away due to issues with paperwork and documentation. In addition, the military received the pension of any ex-soldier who was the recipient of any another pension.

Over time I began to understand what happened and learned why we had been sent there; it was all political. Little by little, I was able to realize what I lived through.

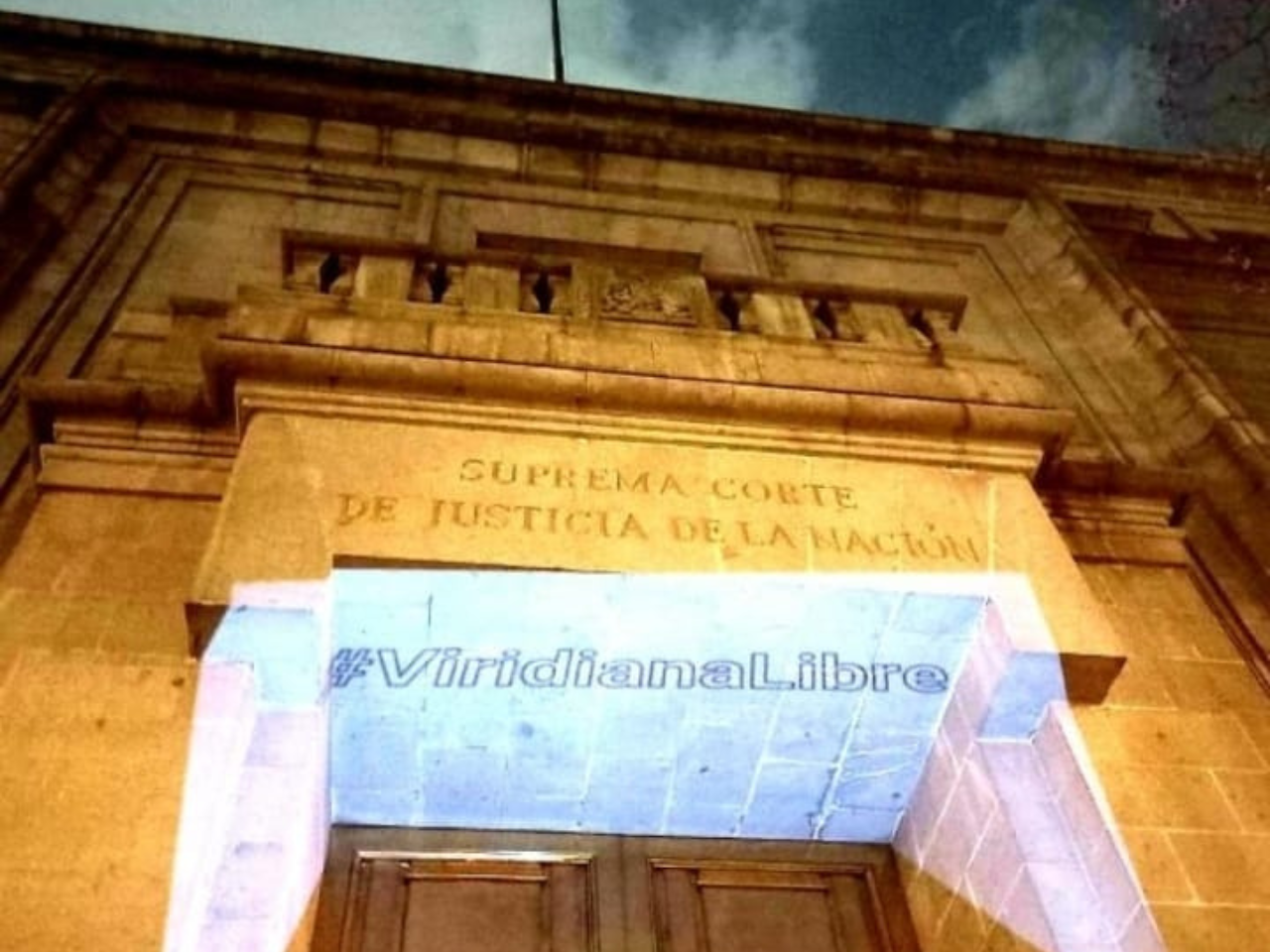

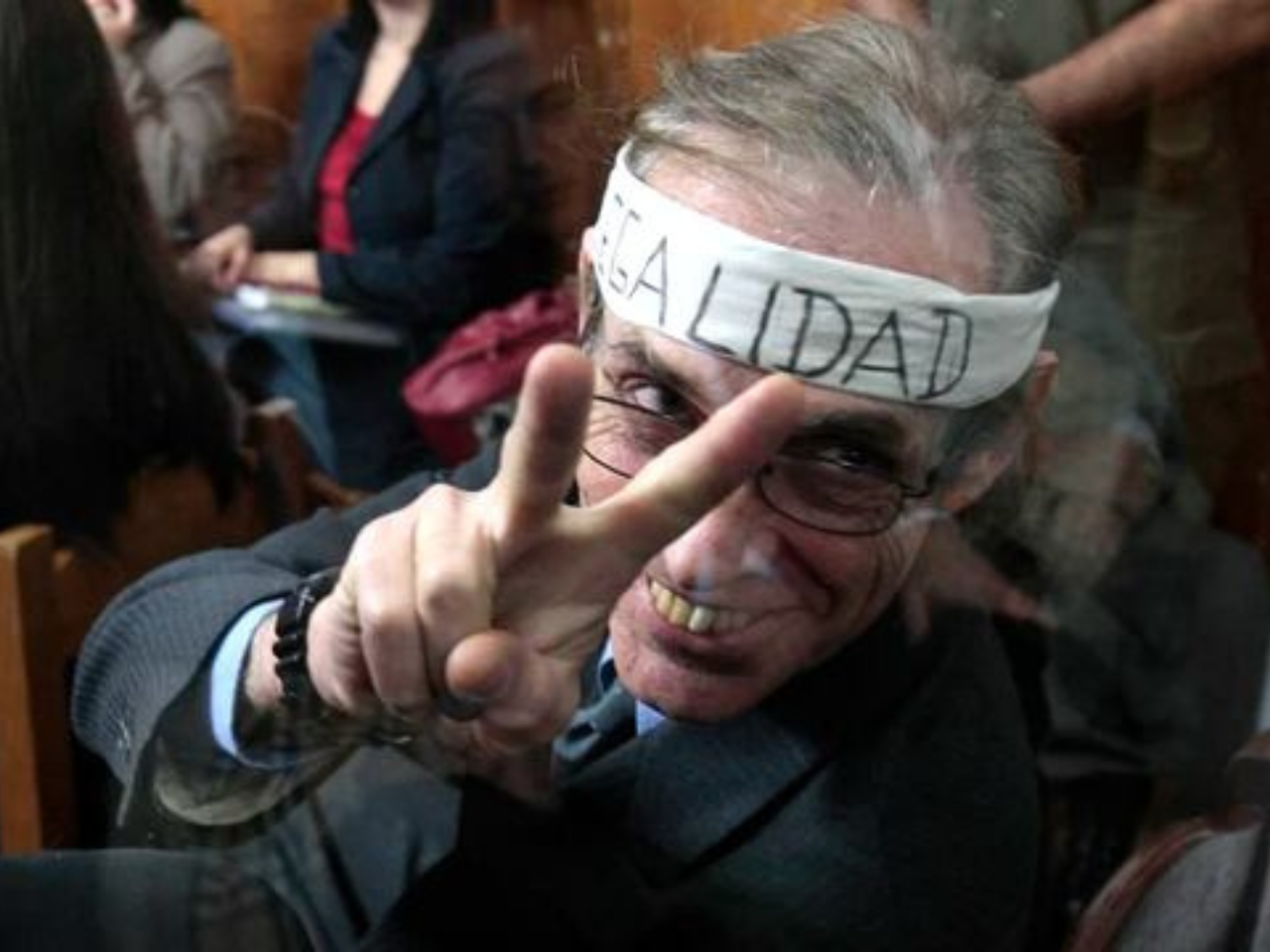

Still seeking justice for treatment as a conscript

The recognition we need is economic and health support, not being named as a soldier. I was forced to fight for a country in which I owned nothing, I had nothing.

The military superiors who mistreated so many of us have to pay for what they did. Cases of abuse and torture are on hold for justice, waiting for the guilty to die without being prosecuted. There were also cases of military spies attending meetings of ex-civilian soldiers to learn what we were discussing. We realized when they did not have the corresponding papers.

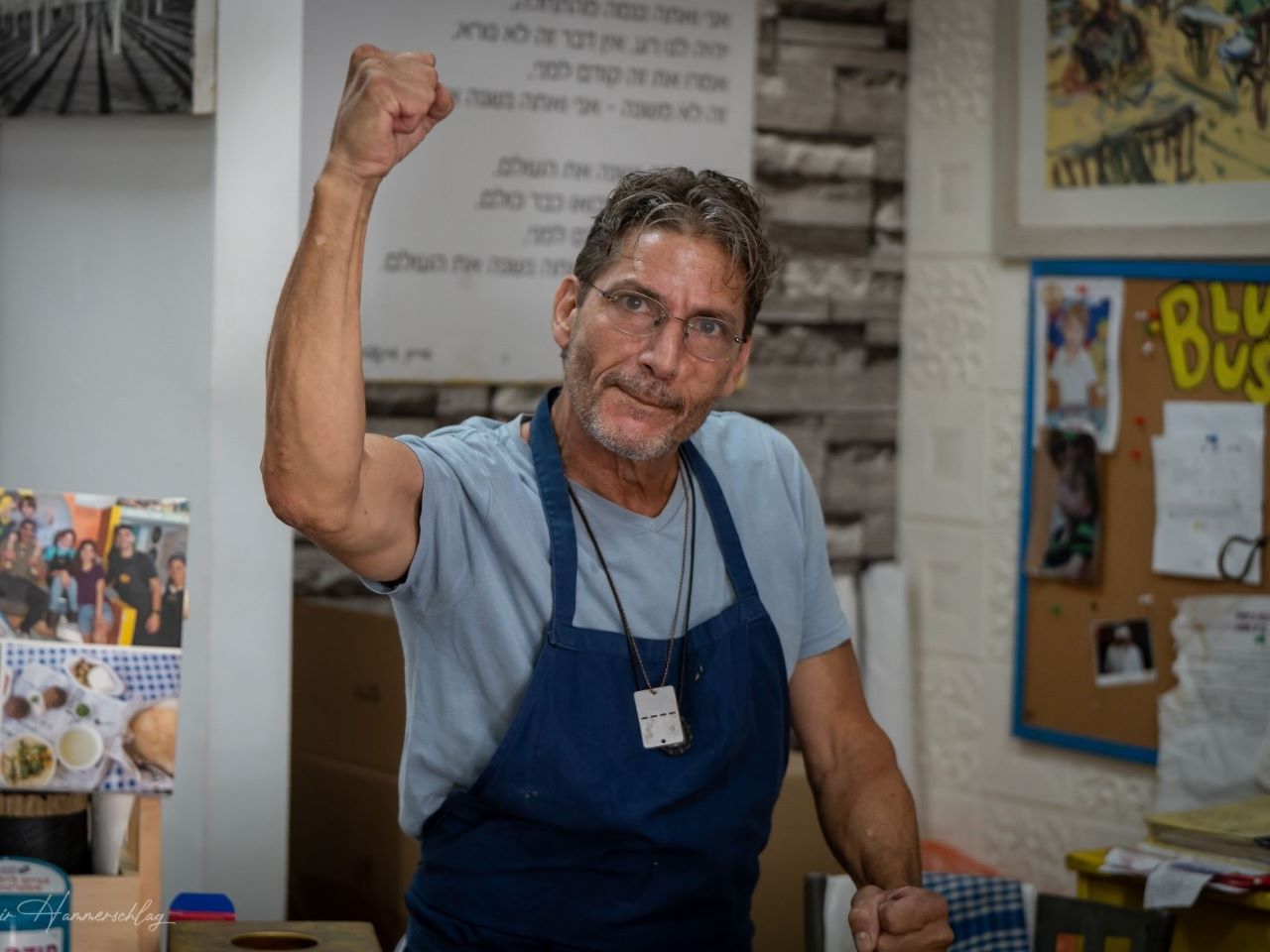

It wasn’t all bad; during my mandatory service and time in the war I made great friendships, discovered music, and learned to play several instruments. I also entered the world of writing—when I came back, I felt the need to write, and an ex-combatant friend took me to writing workshops and taught me a lot.

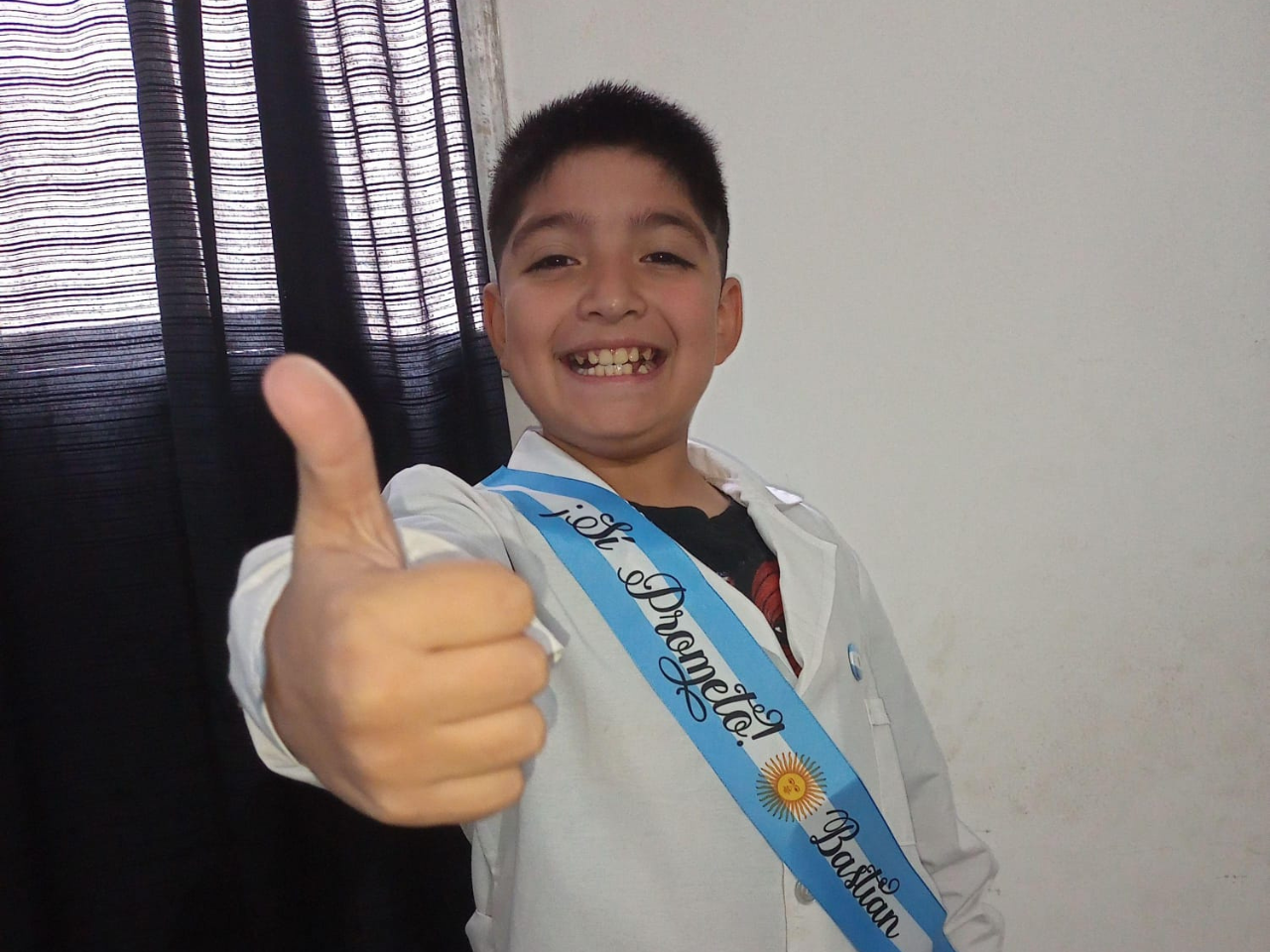

I believe our country is forgetting what happened during the Falklands War, which is exactly what the people in charge want. We have to talk honestly about it, and teach today’s youth what happened to better understand what the political interests of the islands are and why it matters. I feel it is key to creating unity in Argentine society.