American artist in Israel for a wedding cleared dead bodies after Hamas attack: “It is incredibly hard to narrate this, but I will try”

In Be’eri, nothing prepared me for what I saw and did as a volunteer rescuer. Be’eri – once a beautiful kibbutz near the Gaza border with about 1,100 residents – became a shadow of itself. From the second that we set foot in the kibbutz; the overpowering smell of decomposing bodies filled the air.

- 2 years ago

November 27, 2023

TRIGGER WARNING: This story contains extremely graphic content of the violent attack by Hamas on Israeli civilians including babies and may not be suitable for some readers.

BE’ERI, Israel — It was always my greatest wish to introduce my two young sons to my family: not those at home in the United States, but in my homeland of Israel. I longed for my sons to experience my culture, see the place where I spent my childhood, and connect to my roots. My cousin’s wedding seemed like the right opportunity, so I bought tickets and we headed to Tel Aviv.

However, the fun and laughter soon turned into terror and tears. I spent my time in Israel picking up body parts and placing decomposing bodies in bags after the attack by Hamas. The music did not play at the wedding, the beautiful clothes were never worn, and the dances never happened.

Read more stories and op-eds from the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

My children never experienced anything like this before

Attacks on Israel from the Palestinian side of the border are not new to anyone who has lived in Israel. Still, the events that unfolded on October 7, 2023, three days after we arrived, proved unprecedented and horrific. Hamas launched a surprise terror attack on a special Jewish holiday known as Shabbat killing over 1,200 people and taking about 240 hostages.

Like many Israelis and the rest of the world, we did not understand the gravity of the horrendous attack until we moved to shelters, enduring the torturous sound of rockets firing. It was a full-fledged war. My children never experienced anything like this in their lives and the events will forever be etched in their minds.

Seeing my homeland invaded and my countrymen fall into grief triggered my zeal to serve so I enlisted as a volunteer in Israel’s civilian rescue and recovery organization Zaka. Zaka has over 3,000 volunteers working across the country. The volunteers actively respond to any terror attack, disaster, or major accident working in close collaboration with all emergency services and security forces.

Moments before I left for Be’eri, I called my children in to tell them that I had to go volunteer. The shock in their eyes became palpable. I hoped that my actions would give them a sense of pride. I opened the door and walked out as my parents and children waved goodbye.

In Be’eri, nothing prepared me for what I saw and did as a volunteer rescuer. Be’eri – once a beautiful kibbutz near the Gaza border with about 1,100 residents – became a shadow of itself. From the second that we set foot in the kibbutz; the overpowering smell of decomposing bodies filled the air.

Volunteering for my homeland to give bodies identity and some dignity.

As part of a highly specialized unit that clears dead bodies after disasters, going into the Be’eri kibbutz left me horrified. Our special nose masks could not block the stench. It upset the stomachs of many volunteers, so much so, some of them stumbled and threw up.

Over 100 bodies of Israelis, tortured and slaughtered by Hamas terrorists, scattered everywhere. The level of barbarism left even the strongest of hearts broken. As we cleared the neighborhoods, everything we touched seemed to be a human body part. The corpses littered every space and in one day alone, I personally handled 40 bodies.

I used a white plastic cover to wrap the butchered, burned, and cut up human remains. In Israel, I recovered burned babies, a woman who had been shot in the face more than 20 times, dead men, and the elderly. I personally witnessed some babies cut into pieces with knives stuck in their heads, and their fingers placed on top of the body.

I even saw a baby still stuck to the umbilical cord of its mother who had been shot and cut open. Never in my life had I envisioned coming across something this horrendous – not in a movie, let alone in real life. These babies did nothing to deserve such brutality. Each time I collected the body of a baby, I sobbed. All I could see in my mind were my two children. As much as I felt horrified, I remained thankful that my sons remained safe. I saw a baby with no face and an axe left in her head. I picked up the baby’s fingers, arms, and burned body, carefully placing them in the white bag and into the refrigerated truck.

Social media posts claiming no babies were killed felt insulting

When possible, I wrote down the victim’s house number with a marker. It felt like a treacherous task to lift the bodies and place the bag beneath them to cover them up. When a corpse proved too heavy, puffed-up, or already in decay, we wrapped more bags around it, rolling the body multiple times. We had no special tools; just our glove-covered hands.

One day, I entered a house where bodies lay everywhere, and blood covered the walls and floors. Stunned, I ran back outside. When I finally went back in, I put my hands over my eyes to avoid seeing anything except what I needed to see. Every day, I continued the disgusting work of retrieving bodies. While I consider myself strong, what I saw broke me.

Back home, I read the insulting claims online that Hamas butchered no babies. While I did not count the number of infant corpses I saw because I had a task to do, I witnessed the massacre firsthand. Still, the magnitude of carnage felt unsurprising given that Hamas spent about eight hours roaming the kibbutz. They killed most moving things, set homes on fire, then killed those who tried to escape the smoke and flames.

The Israeli military arrived first to clear out the terrorists, then Zaka came in. During my three and a half days cleaning out dead bodies, I saw an unimaginable amount of human blood. Some of the bodies were likely Hamas fighters, but we treated them the same; we did not spit on them. Per protocol, we handed the bodies over to the military. While I don’t know, I imagine they send them off for DNA testing before returning the bodies to their families.

Back in Los Angeles, struggling with trauma

Many years before Hamas attacked Israel on October 7, 2023, a friend of mine who worked for Zaka for 25 years told me stories about his job. He inspired me to volunteer while I was in Israel. Since then, my respect for him has multiplied. While he may not have previously dealt with a tragedy of this magnitude, he worked in the aftermath of disasters.

While I cannot paint a picture of his current state of mind, or that of the other Zaka volunteers, for me processing the horror I witnessed remains incredibly difficult. The unimaginable scale of human devastation constantly reappears in my mind.

While my boys and I returned to Los Angeles, my heart desperately wants to go back to Israel. I yearn to return to my homeland, as thoughts of family occupy my mind. I find it very difficult to remain in the United States right now.

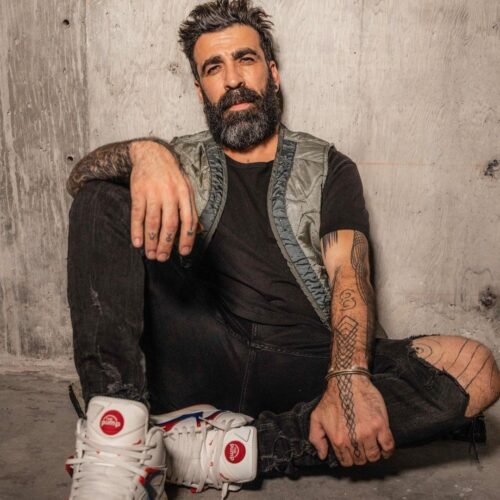

As an artist, I feel things deeply. My art has been an important source in my life, to let out my deepest feelings. Now, I am coping by creating art and spending time with my five-year-old and nine-year-old boys. I try to confine myself to my studio. I believe it will take years – maybe even a lifetime – to process and heal from what I’ve seen.