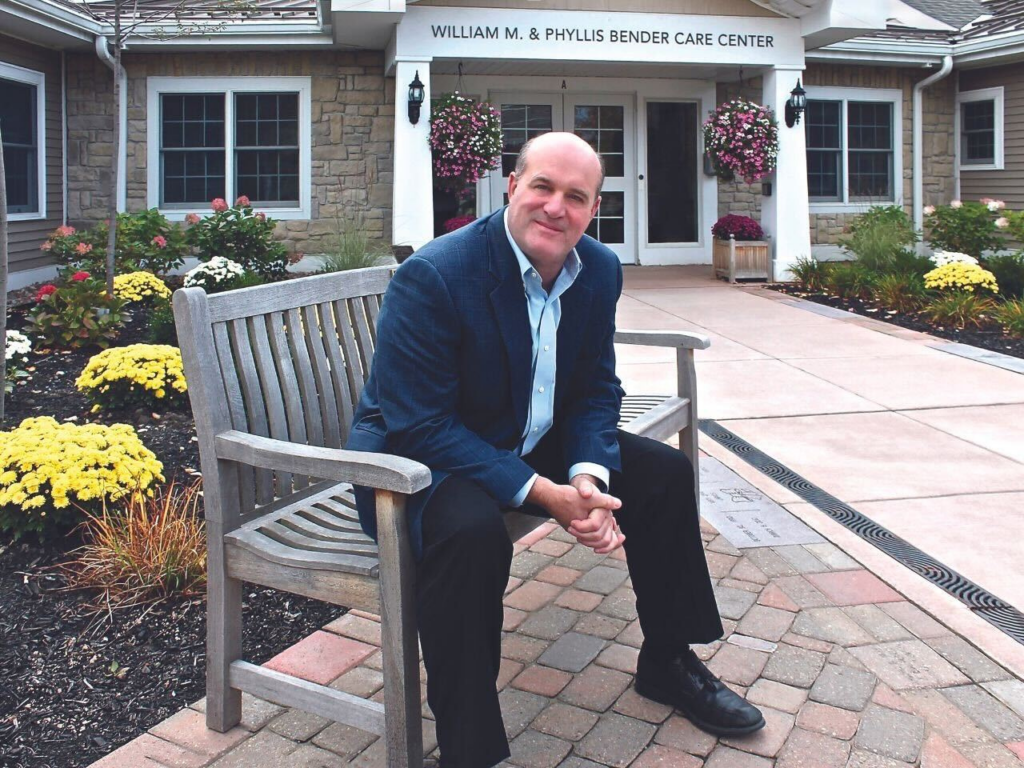

Buffalo physician reflects on 25 years working with near-death patients: “Death is a natural part of life”

Mary, a patient with little time left, seemed normal until she suddenly sat up in bed. She flexed her arms as if holding something and gently rocked them from side to side. Her eyes followed the space in her arms, and she whispered, “Danny.”

- 2 years ago

July 2, 2024

BUFFALO, United States — As a physician with 25 years of experience, I stood by countless patients in their final moments. Witnessing the dying process firsthand profoundly transformed my understanding of death. I observed people, at certain moments, detach from our reality and connect with loved ones and memories in ways that defy conventional explanations.

These experiences not only shifted my perspective but also eased my fear of death. Through these profound encounters, I learned that death is not merely an end, but a deeply personal journey filled with unexpected connections and moments of peace.

Related: End-of-life doula shares the beauty to be found in death

First encounter with near-death patients

In 1999, at 36, my professional life shifted entirely. One day, during my rounds, I entered a room where Mary’s family had gathered. Mary, a patient with little time left, seemed normal until she suddenly sat up in bed. She flexed her arms as if holding something and gently rocked her arms from side to side. Her eyes followed the space in her arms, and she whispered, “Danny.”

Everyone froze, utterly bewildered. What happened made no sense. Mary completely detached from the rest of the room. Her world narrowed to herself and whatever she saw. She didn’t remember; she lived a present experience. The moment felt so intimate that we just stood by and respected it. Mary entered a world of her own.

When her sister arrived, she told us that Danny was Mary’s first child, a baby she lost soon after birth, and now, somehow, they were being reunited. Just as suddenly as she entered that trance, she came back to us. She settled back into bed and resumed her conversation with her family as if nothing unusual had happened. To her, indeed, there was nothing strange about it. It was not a dream or a memory, but something natural.

The experience hit me hard and implied a drastic change in my perspective. I realized that terminal patients have a different view of life and the world, a unique perception. At that moment, I decided not to invalidate their experiences just because I couldn’t explain them rationally or scientifically. I understood that my role was to accompany those moments and study them.

Related: Ana Estrada becomes first woman in Peru to legally access euthanasia

Death as a natural part of human life:”I expanded my capacity to deal with the intangible”

By immersing myself in this universe, I began to shed my prejudices. I expanded my capacity to deal with the intangible. I initially approached my research with the frustration of not understanding what was happening, but I came to accept that the patients were not confused or delusional. This allowed me to realize that death was not a medical failure, as I had previously believed, but a natural part of human life.

Years later, I witnessed something extraordinary with Jessica, a 13-year-old girl whose death was imminent. She struggled to talk to her mother about her impending death and had no close encounters with death except for a friend of her mother. Jessica had two experiences that helped her come to terms with dying.

First, Jessica had vivid dreams of encountering a pet that had passed, a dog she saw bouncing around happily. She knew she would not be alone when she died. Another day, in the middle of her room, she experienced a vision. Her mother’s friend appeared, talked to her, and assured her someone would be there to look after her wherever she went. The girl’s demeanor changed considerably. Peace washed over her face and temperament, and this calmness spread to her mother despite her sense of loss.

As a doctor, witnessing something like this is very rare. I felt more was happening than I could understand. At the same time, I felt privileged because, in these terminal moments, one sees the best of humanity. We often have very negative ideas about death, but in my experience, it can be a very positive experience. These moments towards the end highlight the importance of life.

Rate the experience’s realism from 0 to 10: most patients choose 10

Another time, I served an elderly patient who fought in Normandy during World War II. Throughout his life, he felt guilty for surviving while his comrades fell in combat. Towards the end of his life, he relived the horrors of war repeatedly. It felt heartbreaking to watch as he shook and tossed in his sleep, agitated, until he woke up startled and full of anguish.

One night, he slept relaxed. He had dreamt of his comrades coming to his rescue and finally found closure. Half of the patients I spoke with tell us they remain awake when these experiences occur, while the other half say they are asleep. When we ask them to rate how real the experience felt from 0 to 10, the vast majority choose 10, including the soldier.

A while ago, I observed another moving experience. This case was particularly typical. An 95-year-old elderly man whose mother died when he was a child, remained close to death himself. Suddenly, his whole bodily attitude changed. He seemed ready to talk to someone not visible in the room. A deep love appeared in his gaze as he kept his head down, looking up.

We later learned that after 90 years, he became a child again and reunited with his mother. It was as if time and distance evaporated. At that moment, I became certain that a kind of love always surrounds us and never disappears. This is something I have witnessed in my work. All these experiences led me to believe that, even as we die, we continue to experience spiritual and psychological growth. It is a paradox.

As an oncology patient, I no longer fear death

As an oncology patient myself, I have thought about my death more than I would have liked, even though I am doing well in my treatment. After working for so many years with terminally ill patients, I now have very little fear of the dying process. I think nature offers us a gentle way of guiding us through our final moments. I can’t help but wonder what it will be like to reunite with people I love and have lost, like my father; what it will be like to hear his voice again. In a way, I am looking forward to it.

Sometimes death is defined as emptiness, as physical deterioration, but we can also view it in a much more positive light, focusing on the connections that are created. These experiences towards the end of life often make the patient value the life they have lived even more. When they see this, families also appreciate the experiences their loved ones have had, valuing these final moments deeply.

It makes a lot of sense that in the last moments of life, patients start to reflect on what truly matters. They stop thinking about taxes, bills, and other mundane concerns. Instead, memories of what is genuinely important, stored deep within our brain and body, naturally come to light.