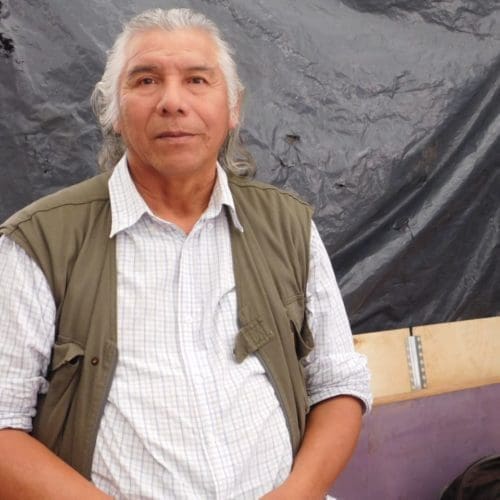

Indigenous community camps near Presidential office for two straight years: Who will help us?

Camped out in front of the Plaza de Mayo in Buenos Aires, my people merely survive. It feels like being in the desert. We sell handicrafts to live, but food remains in short supply. Pain fills me, knowing so many different sectors which could help ignore us.

- 3 years ago

March 24, 2023

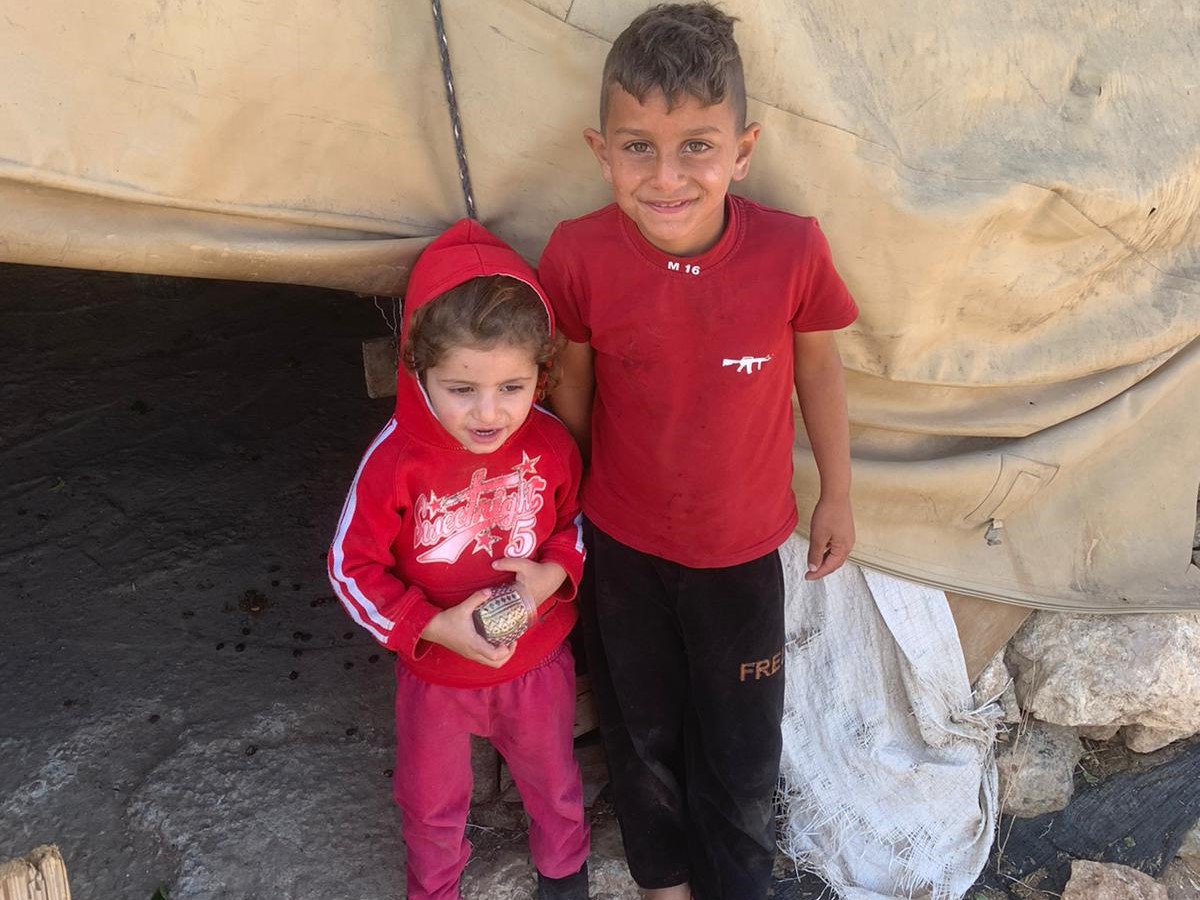

BUENOS AIRES, Argentina ꟷ On February 8, 2023, indigenous people of Argentina commemorated two years of camping out in front of the Plaza de Mayo. [Plaza de Mayo is the oldest public square in Buenos Aires, adjacent to Casa Rosada, the office of the Argentinian president].

For many of us, this day-to-day experience feels like torture. We have nothing in our camp and suffer through extreme heat. The blowing winds create a precarious situation for our tents. We have no bathrooms or electricity and must go somewhere else to use a washroom; yet we do this to demand the state establish necessary laws.

Read more first-person news from indigenous communities around the world.

My people need an intercultural dialogue between the Argentine government and the indigenous people to solve serious problems. Our communities face a lack of water, healthcare, educational opportunities, and access to our own land and territories.

We know this fight. Facing abuse, discrimination, and isolation remain a constant for Argentina’s indigenous communities, but we do not want it normalized. So, we demand the state listen. We speak out to end these problems once and for all.

A plight for resources and humane treatment: our women are dying

In the indigenous communities of Argentina, problems worsen every year. In many communities, the people have no water and no access to healthcare. Drugs flood our lands and young people kill each other or commit suicide. We lack appropriate justice systems and access to positive policing, and have nowhere to channel these problems; no one to go to.

For more than 724 days, we have stood in front of the plaza and the presidential palace because we need help and answers from the national government to solve unfair problems facing our communities. Each day, we wait, longing for a dialogue with the executive branch; longing to be heard.

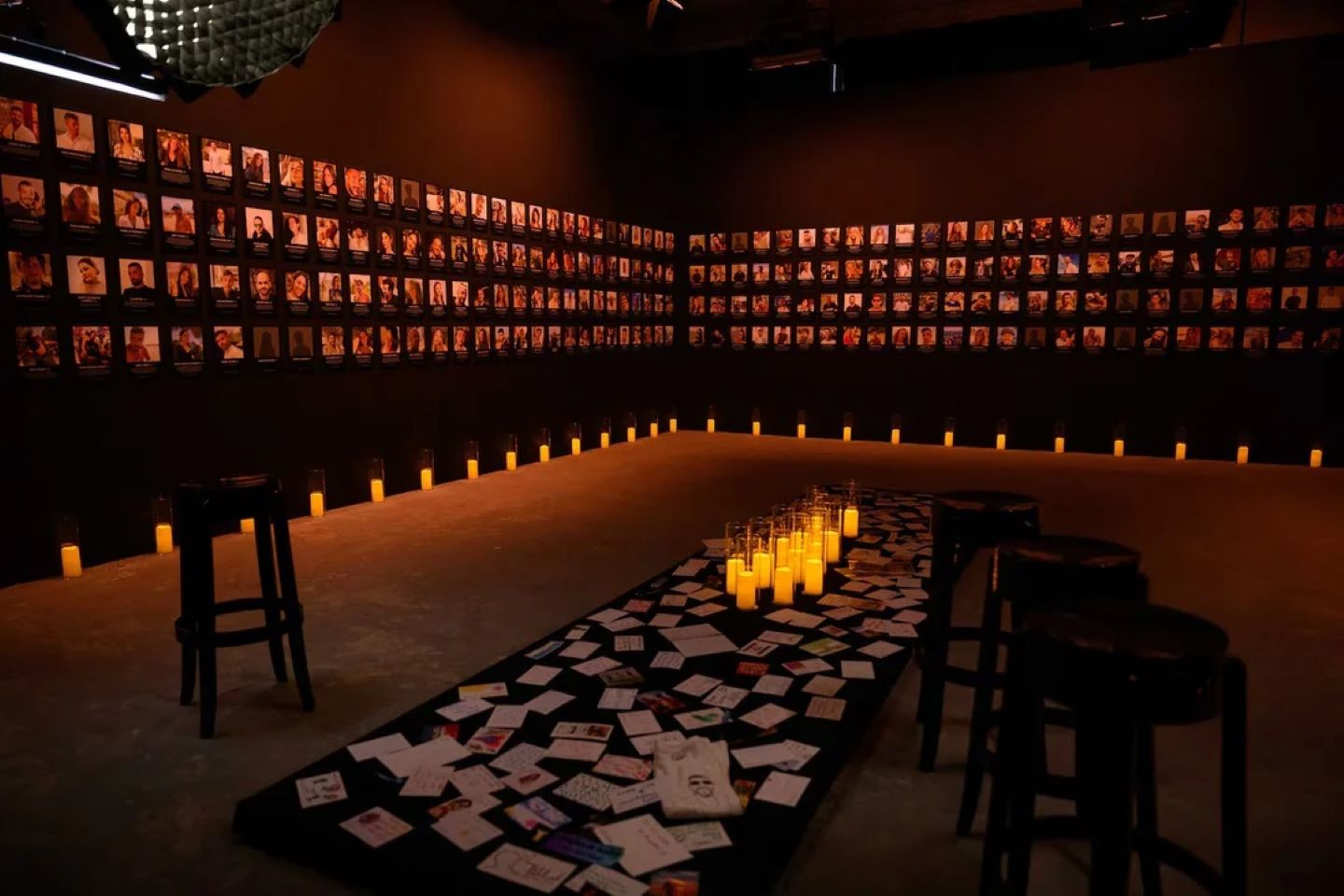

Back home, a doctor shows up to see our people every 20 days or once a month. The doctor checks people over but not thoroughly or properly. When the doctor leaves, people die. The diseases they succumb to – like tuberculosis, pneumonia, and some forms of cancer – could be easily treated. This scourge of illness marches through our communities, often among women, because they lack knowledge about simple prevention. We stand here in the plaza because our people die pointlessly; we need a health center equipped with permanent doctors.

Another frightening issue arises with our women’s reproductive health. If she faces a cesarian-section, we see cases where, after the birth, with no consultation, the doctors implement a method of contraception to prevent having more children. Women fear even going to the doctor for this reason. In other reported cases, the doctors hand out condoms, birth control pills, or offer injectables, but offer no education on their impact or usage. Women die and we do not know why. They record the deaths as natural and any further research ends right there.

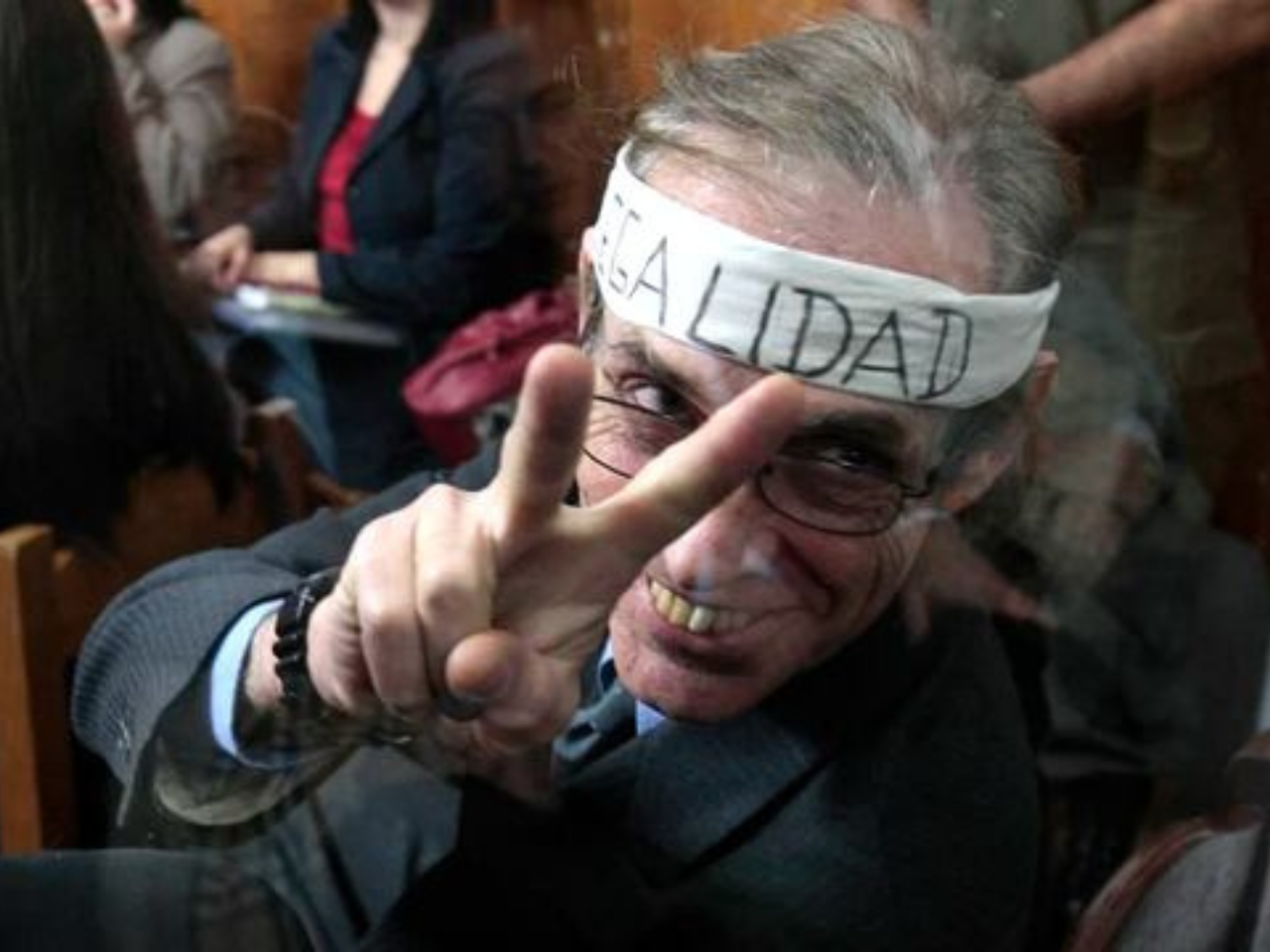

A history of fighting to be heard: indigenous leader travels all the way to Rome

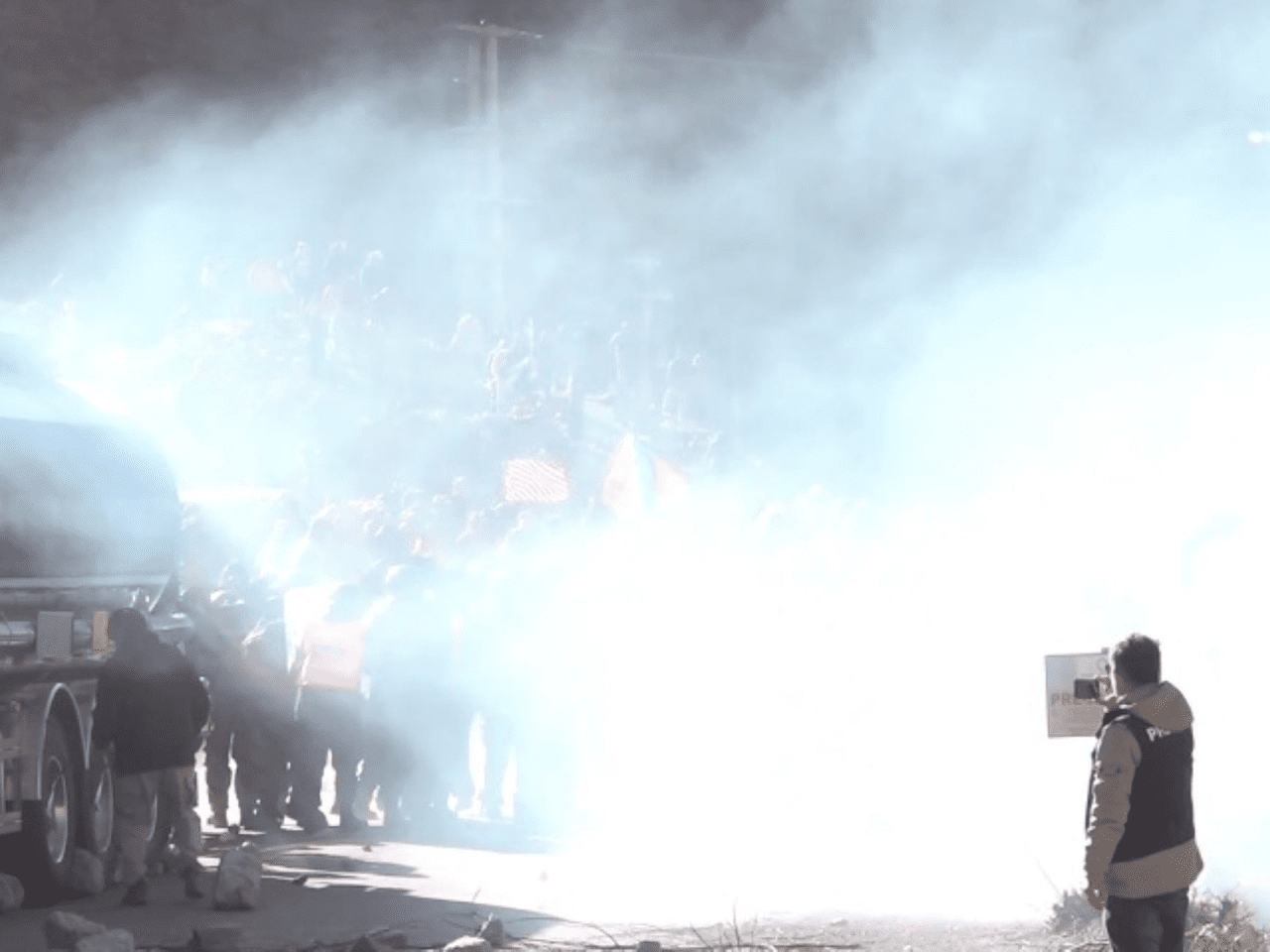

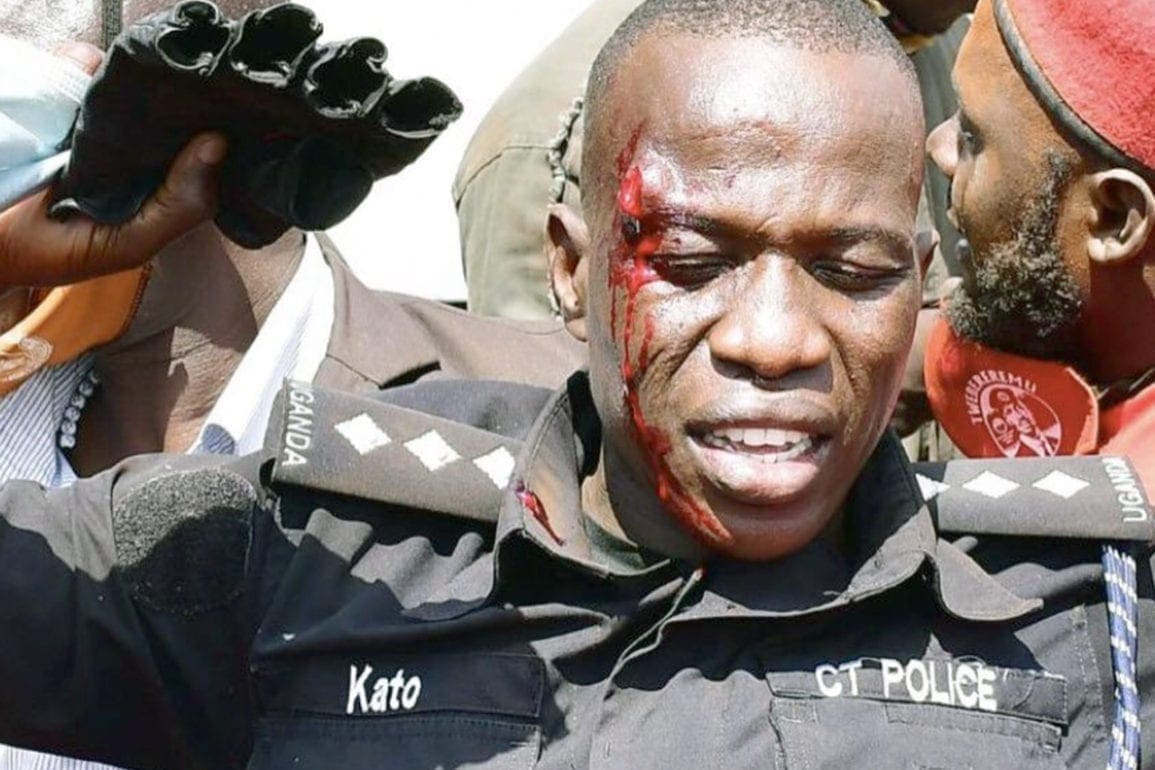

In 2007, the government of Formosa, through Governor Gildo Insfrán, took 2,042 hectares (5,000 acres) of our ancestral land. For 16 years, we have demanded a territorial survey, but it never happened. Again, in July 2010 I went on the road with my people. By November, we faced harsh repression. [For four months, the people of La Primavera, or Qom Potae Napocna Navogoh, blocked National Route 86. The protest against building a National University on indigenous lands led to police violence and shooting. A protestor and policeman died, several were injured, and houses burned. The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights intervened, demanding the government stop the violence.]

The spiritual and religious leaders recommended I travel to Buenos Aires to speak with President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner. She did not receive us. Three years passed and we turned our attention to the Catholic Church. They established different missions in the Formosa province. We wanted the church to understand the territorial issues facing our people. I traveled to the Vatican to speak with Pope Francis. That day, the Pontiff said the Church manages only spiritual matters; the governments remain autonomous. He could not intervene or communicate our concerns.

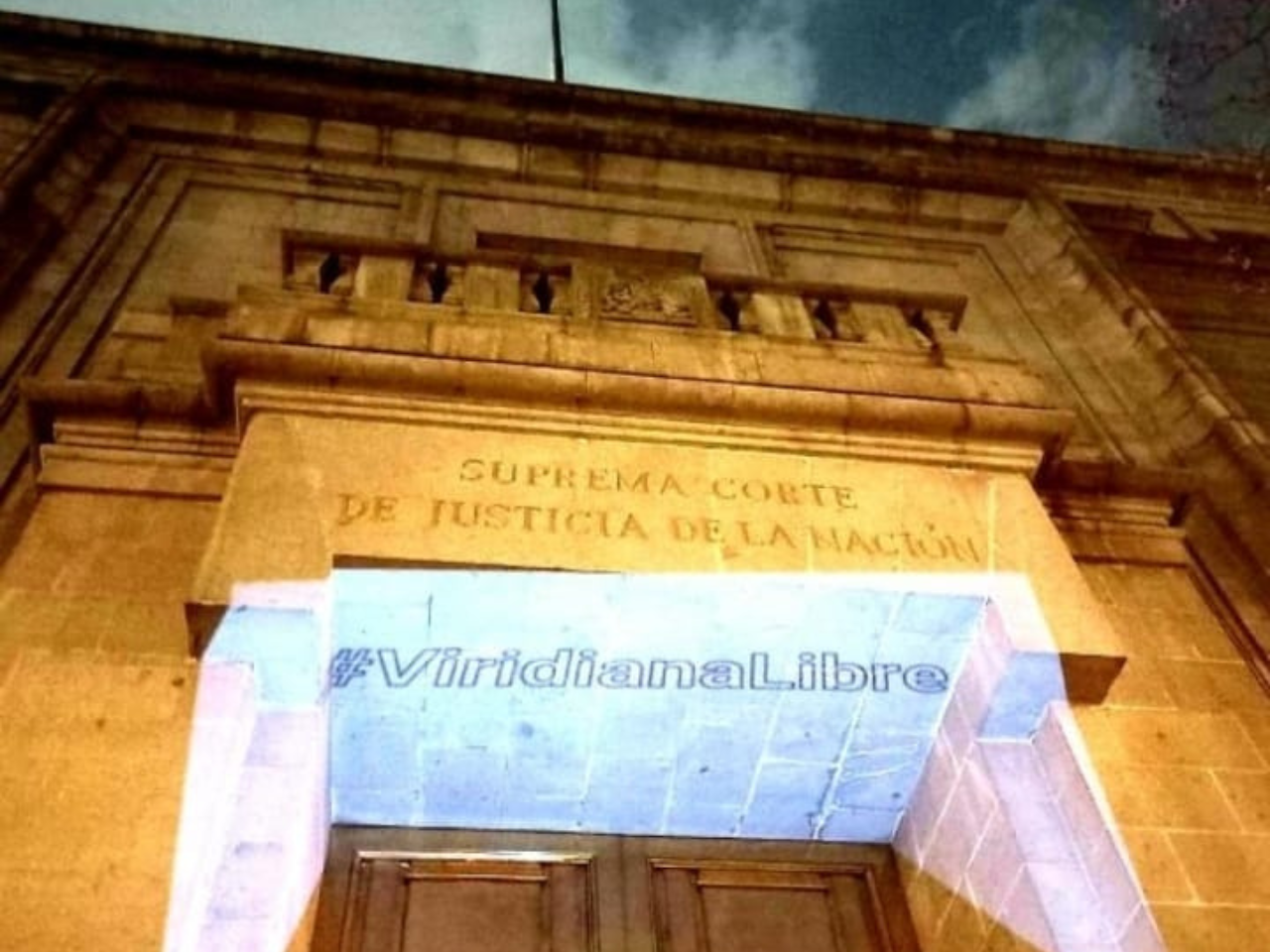

Finally, in 2016, the Argentine government established what is known as the Consultative and Participatory Council of Indigenous Peoples of the Argentine Republic. [The document acknowledges the United Nations declaration on the rights of indigenous people. It also points out Argentina’s own constitution legally recognizing indigenous people and their needs in the territory. The new council gained the ability to consult on legislation, development plans, programs, and projects directly affecting indigenous rights.]

This long battle continues, six years after the formation of the council. Sitting in the plaza day after day, we demand the council’s restoration. We must be heard. The indigenous people of Argentina deserve to dialogue with the government.

Day to day life during two years of protest

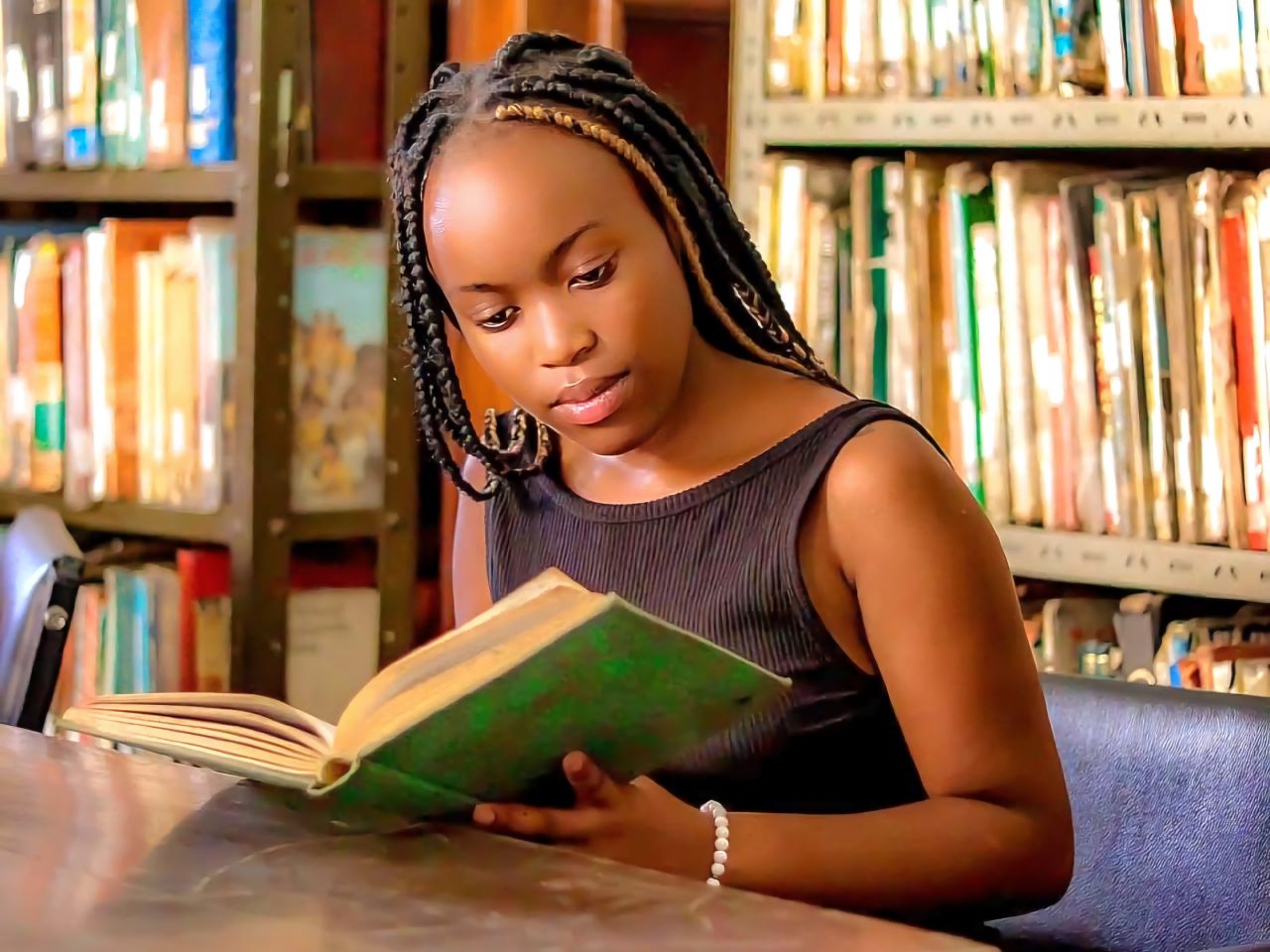

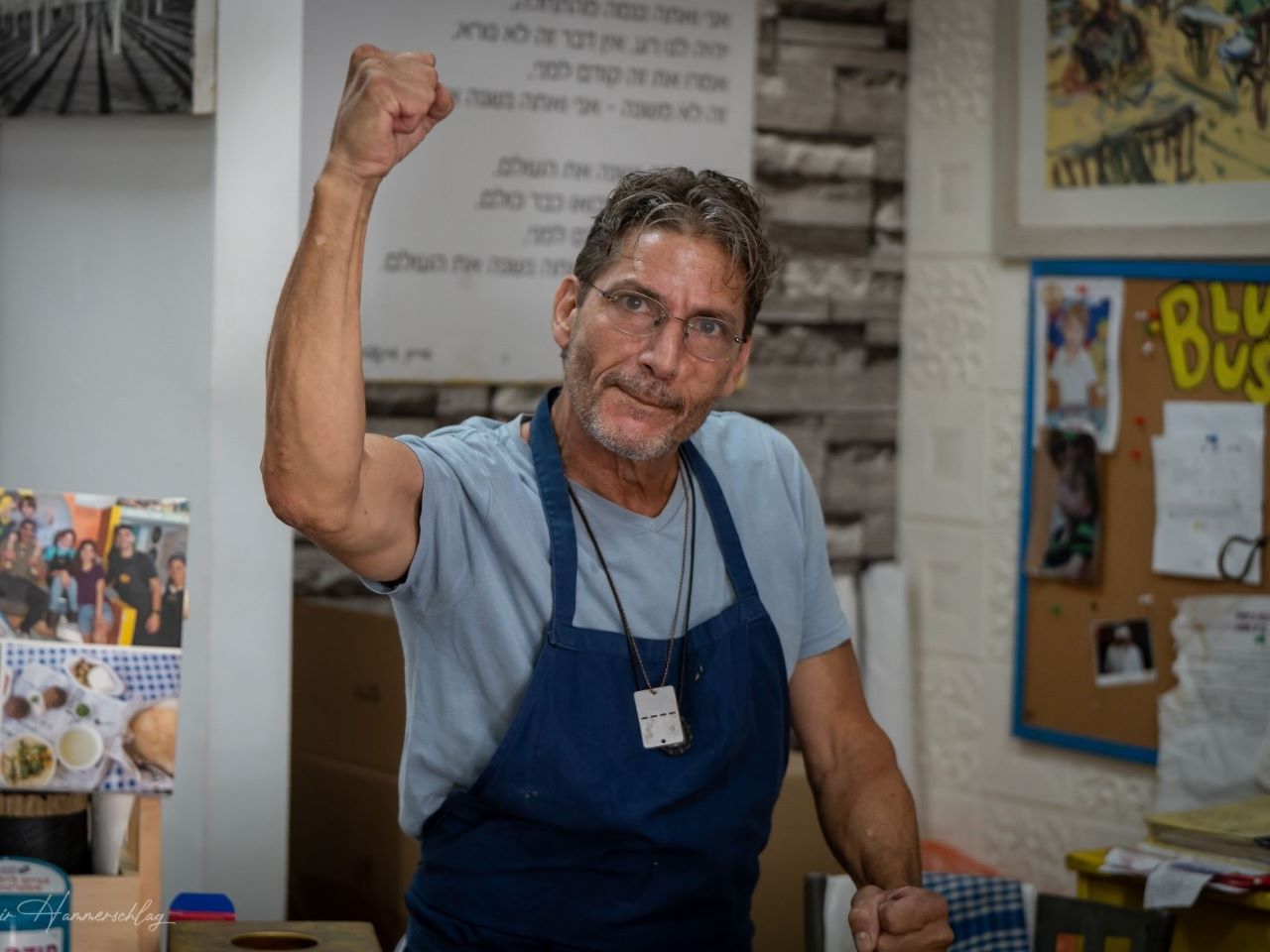

Camped out in front of the Plaza de Mayo in Buenos Aires, my people merely survive. It feels like being in the desert. We sell handicrafts to live, but food remains in short supply. Pain fills me, knowing so many different sectors which could help ignore us. We receive no support from human rights organizations, social movements, or churches. Even so, we persist.

During these two years, I fell ill with Covid-19 while camping, and spent 18 days in the hospital. Dizziness and cramping constantly affected me. Tremors ran through my body and terrible pain struck my chest. I survived and returned to the plaza, but for a year, my health issues persisted. I was lucky. During the Pandemic, many indigenous leaders died from lack of access to healthcare.

We carry on today, even amidst the precarious economic situation facing citizens of Argentina. We struggle to sell our handicrafts and buy the food and water we need, but we remain calm. At first, city police threatened to evict us, but we stood our ground. We refuse to remain spectators in our own struggle. Today, we strive to be actors. We demand change.