The challenges of our time see no borders, responses to those threats remain inadequate and dangerously short-sighted

We must come to peace with the fact that the challenges of our time see no borders. Nationalistic discourse is not only outdated but dangerously short-sighted when used to interpret the world before us. The effectiveness of the individual nation states in meeting these challenges is incomparably lower than the solutions that can be obtained by collaborating internationally.

- 2 years ago

July 1, 2024

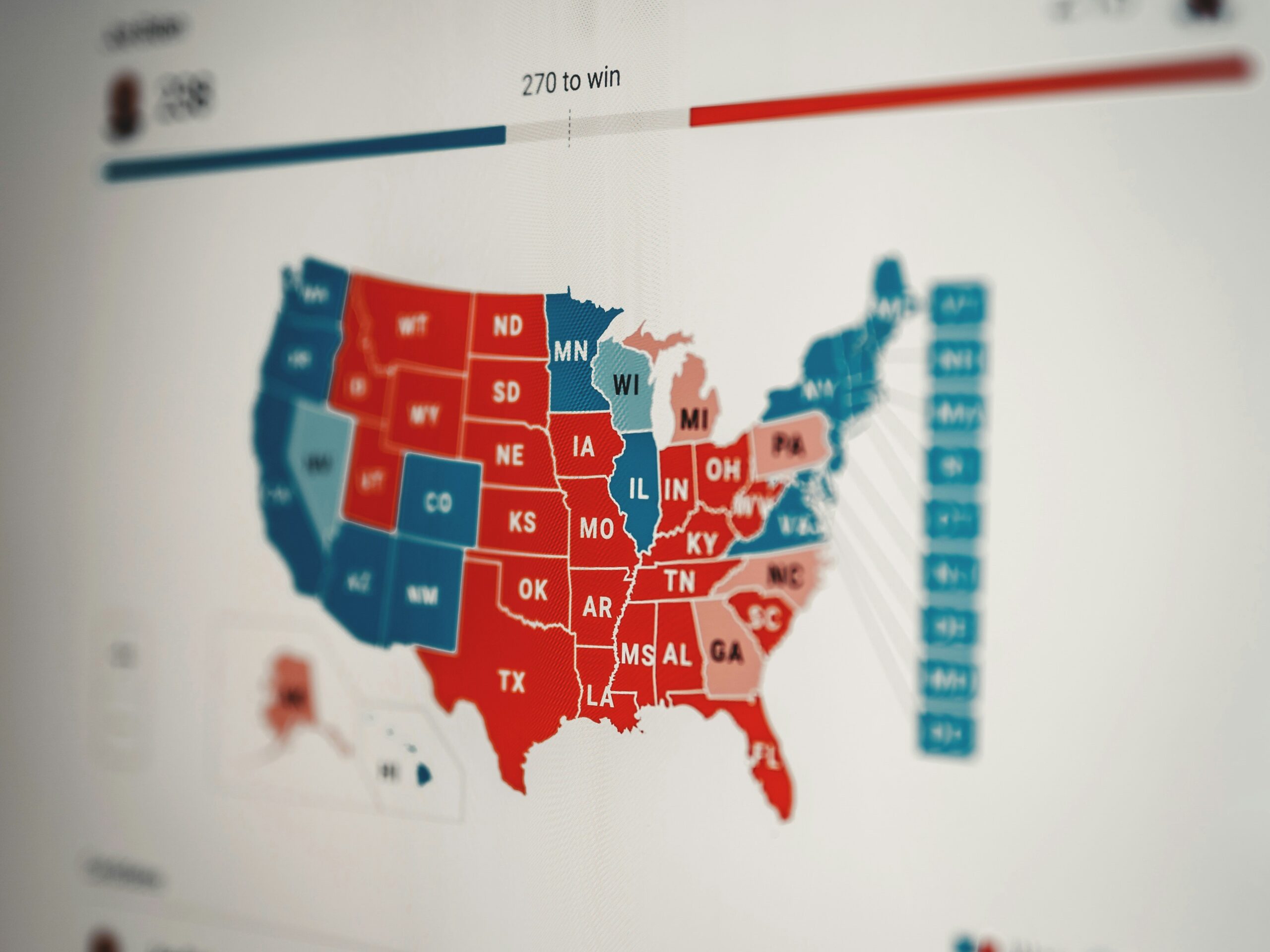

In the aftermath of the 2024 European elections, the broad European political center – which spanned from conservatives to liberals, and greens to social democrats – is about to crumble. Not in a tsunami-landside to the far right as some polls predicted, but in a bit-for-bit erosion.

The far right now holds about 25 percent of the seats (180 seats) in the house. This number spreads across multiple groups. It includes the European Conservatives and Reformists (ERC) and the Identity and Democracy (ID) faction. It also includes a possible new group forming from the unaffiliated extreme fringes of European politics dubbed the Sovrainists. The Sovrainists may be the method the Alternative for Germany choses to pressure ID to take them back.

Yet there is more. While the extreme right parties’ performance has been variable (from scaringly impressive in Austria and Belgium, to below expectations in the Iberian peninsula) their effectiveness seems particularly threatening in the three biggest economies of the EU: Germany, France and Italy.

Global conflict, financial crises, and COVID-19 seem to lead young adults to the far-right

We can partly explain the rise of the far right by the human tendency to romanticize the past. I have heard somewhere that while horses have an almost 360-degree vision, fish can only see what’s on the side of their heads. Humans, on the other hand, can only look at what’s ahead of them. Maybe that is why it is easy to tell ourselves stories about how good the old times were. These dynamics fuel the rise of the far right in Europe almost exactly one century after the dawn of fascism.

The generation that lived through World War II is dying. Most contemporary Europeans don’t have memories of Fascism and Nazism. My generation, instead, has vivid memories of the many crises it experienced. We were in our adolescence or entering adulthood around the mid 2000s. For us, it started with the 2008 debt crisis, followed by the 2012 financial crisis, and the so-called 2015 European refugee crisis.

In 2020 the Covid-19 Pandemic emerged. This led to a subsequent cost of living crisis, fueled by the 2022 Russian full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Less than a year ago, the war in Israel/Palestine re-started, causing a huge social divide outside the war zone. In the background, human-made climate change morphed into a full-blown crisis, threatening to sweep away our future on this planet.

Our challenges did not stop there. While these crises kept us in suspense, social and technological changes transformed our ways to work and interact. This increased pressure to relearn and adapt, feeding a collective feeling of anxiety and uncertainty.

Social media creates vacuum for “beaten-up” generation

Social media made our lives more interconnected globally. It turned the power dynamics in fields spanning from arts to information, interpretation and organization, upside down. Everyone can start a trend, launch a campaign, and go viral. It also opened the gates to disastrous disinformation campaigns, playing a fundamental role in the shameful mess called Brexit. These campaigns contributed to the election of an openly Islamophobic, racist, sexist president of the United States – allegedly the most powerful man on earth.

Social Media allowed us to witness these historic events more closely than any other generation before. The images of dead bodies on the Mediterranean shore, live streams of the brutal terrorist attacks by Hamas, images of Palestinians being tortured and humiliated in Gaza, starving children in Sudan: all of it is just one click away, available to everyone who owns a smartphone.

This beaten-up generation was finally gifted with the gig economy, courtesy of technological advancement and 30 years of deregulation and liberalization. With it came job insecurity, income instability, and lack of worker protections.

How easy is it in this frightening picture to be overwhelmed or scared. We let ourselves be persuaded that we just need to go back to the way we were. This is exactly the tempting and comforting narrative of the far right. In a past when one salary was enough for an entire household, there was no feminism with its annoying demands on reproductive rights and equal pay. There were no other cultures, languages, or ways of understanding life with which to deal. No one was telling us that eating meat or driving a car was ruining the environment and our own health. At least, it’s easy to imagine that there wasn’t anything like that.

What happened to values in politics?

Trust in institutions and mainstream parties crumbles because of their perceived and actual inability to deal in a fair way with the enormous changes and crises our society has undergone. The ensuing distrust directly feeds the rise of undemocratic forces. While disagreeing with the proposed political solution, there is merit to say traditional mainstream parties have not been able to interpret and be on top of the challenges of our times.

There are multiple layers to unravel in this tangle. I believe they can be condensed in three fundamental steps: the need to go back to value-driven politics, the need to recognize international challenges, and – when it comes to Europe – reform the EU.

For starters, having the guts to go back to value-driven politics means being clear about what kind of society we want to build. In my view, for example, a modern progressive political force would have a position similar to this: the green transition needs to happen – and it needs to be socially just. The economic system needs to be stabilized and flourish – and not at the expense of medium to low-income households. Innovation is good for society and for the economy. The rich and ultra-rich need to be regulated and taxed effectively.

The economy needs to stay competitive. In this interconnected and interdependent world, it is better to create synergies than rivalries. Migration needs to be accepted as a human phenomenon instead of a crisis. We need to make sure that the receiving system is fair, humane, and effective for the welcoming and welcomed communities.

Secondly, we must come to peace with the fact that the challenges of our time see no borders. Nationalistic discourse is not only outdated but dangerously short-sighted when used to interpret the world before us. The effectiveness of the individual nation states in meeting these challenges is incomparably lower than the solutions that can be obtained by collaborating internationally.

Reform and reconciliation must occur in politics across borders

Finally, from a European perspective, we must embark on much needed reform so as to make the EU become a politically legitimate actor, truly democratic, and understandable by citizens to enhance their participation.

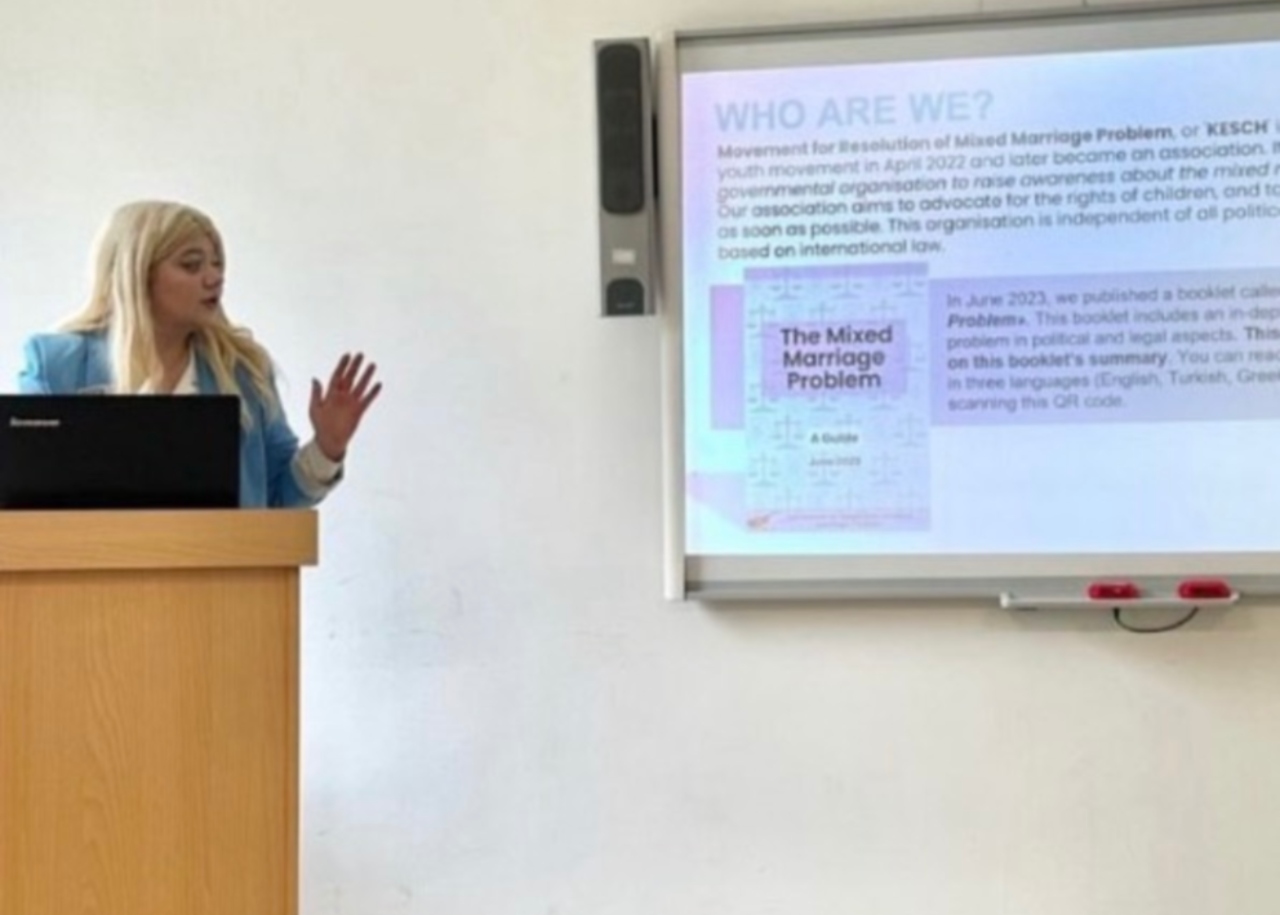

These premises to be effective, though, need to be accompanied by a deep reconciliation between citizens and politics, with the intent of creating a cross-border common vision of a livable future. This is the bet we made when we founded Volt Europa, the pan-European political project. We started in 2018, and currently account for 150+ elected officials in different EU member states. During these past European elections we ran in 15 countries with the same programme, finally gaining 5 seats in the European Parliament.

Our wish is not to remain the only attempt for pushing for a collaborative cross-border approach, but to inspire others worldwide to build a new form of political representation, in recognition of the political needs of these dire times.