Saving the Pink River Dolphins: National Geographic’s Explorer of the Year

Early in my work, one morning at around 5:00 a.m., we set out. At the river, the sun peeked over the horizon and a dense, low fog covered everything, like you see in scary movies. Suddenly, a deafening noise erupted and surrounded us. Dolphins began jumping right in front of the boat.

- 2 years ago

August 2, 2024

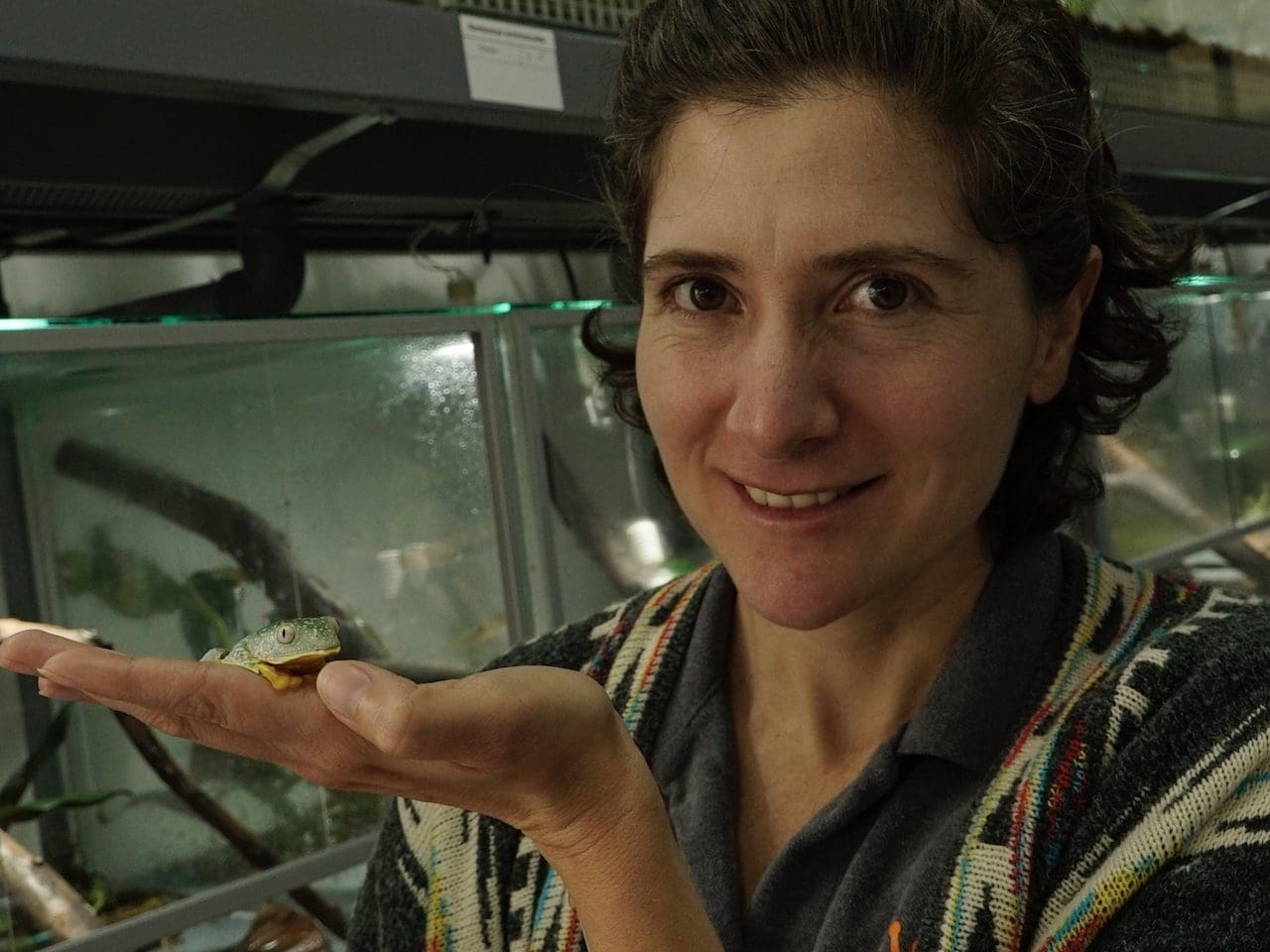

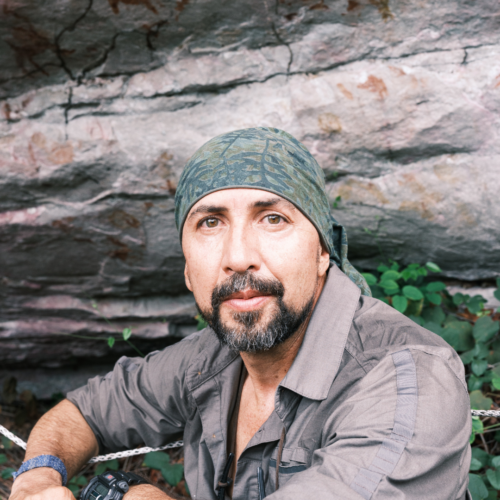

PUERTO NARIÑO, Colombia — For 37 years, I have worked and developed a deep connection with the Pink River Dolphins of the Amazon. From the moment I learned about them, I felt a bond and embarked on a mission to fight their extinction. To do this, I combat the destruction of nature in Colombia. As a result, in 2024, National Geographic recognized me as their Rolex Explorer of the Year.

Read more environment stories at Orato World Media.

Rolex National Geographic Explorer of the Year: “I felt unworthy and completely taken aback”

One day, while working in my office in Bogotá, I received an urgent message from a National Geographic deputy director. He asked for an immediate video call. Since we collaborated on the Perpetual Planet Amazon Expedition, I feared something had gone wrong. However, during the call, he announced my selection as the Rolex Explorer of the Year.

I felt surprised, having attended the award ceremony the year before, populated by people who left a significant impact on the world. I felt unworthy and completely taken aback. After the call, I thought it may have been a figment of my imagination. Only when another member of the organization called to congratulate me a few weeks later did I believe it was real.

My love for nature began in childhood. My grandfather often took us to Puerto Carreño, a border area between Colombia and Venezuela along the Orinoco. There, my grandfather interacted with nature while my brothers and I swam in the river. Before jumping in, we threw stones to scare away piranhas and used sticks to ward off stingrays. We swam and played until someone shouted “Toninas” [Pink River Dolphin], and everyone hurried out of the water.

I wondered, what is this animal everyone fears? It seemed like a ghost or a myth. I never saw a Pink River Dolphin until several years later. While studying at university, I learned it was an Amazon River Dolphin. I still find it ironic, the mammal I ran out of the water to get away from in childhood became the subject of my greatest passion.

Meeting the enigmatic Pink River Dolphin: “Suddenly, dolphins started jumping in front of the boat”

When I started studying marine biology, everyone told me no dolphins existed in Colombia. By chance, I attended a conference with Jacques Cousteau, whose documentaries greatly influenced me. On his way to the Amazon for an expedition, he said, “Nobody is studying dolphins in the Amazon River.” That resonated with me.

At 19, during my sixth semester of university, two classmates and I flew on a cargo plane to the Amazon to study these dolphins. Upon arrival, I felt awe and vulnerability. Despite vacationing in the wilderness all my life, the vastness of the world’s largest rainforest overwhelmed me. My first thought was, “What did I get myself into?” We landed at night in a small village teeming with vegetation. The next morning, as dawn broke, we discovered the beauty of Puerto Nariño, which became my home for the past 37 years.

Puerto Nariño is primarily an indigenous town populated by the Ticuna, Cocama, and Yagua Indians. Some settlers from other parts of the country set up shops and businesses there. The town prohibits bicycles, cars, and motorbikes, so people walk. The organized layout and the complete lack of waste makes for a beautiful place where the residents immediately treated me kindly.

I felt spellbound by Puerto Nariño. Early in my work, one morning at around 5:00 a.m., we set out. At the river, the sun peeked over the horizon and a dense, low fog covered everything, like you see in scary movies. Suddenly, a deafening noise erupted and surrounded us. Dolphins began jumping right in front of the boat. They disappeared into the mist and jumped again. Seeing the dolphins for the first time felt like pure magic.

Years in the Amazon: Beyond scientific explanation

Almost immediately my childish fear of dolphins vanished, replaced by fascination. Today, after so many years, I still marvel at seeing macaws, toucans, jaguars, and dolphins in the water. These experiences feel like a miracle. When I enter the water, I remind myself, “I am entering another realm.” I thank the spirits for being there and carry good energy. I never know what I might encounter. Anacondas, caimans, and other dangerous animals could be present.

Years in the Amazon revealed experiences that go beyond simple scientific explanations. City life dulls the senses; people no longer look at the sky or ground, nor smell the air. In the Amazon, your senses awaken. Indigenous people taught me how to see the bird I only heard, how to smell a snake, and how to remain aware of everything around me. Journeying through this terrain exalts the senses.

About 20 years ago, an indigenous woman approached me, saying, “You do a good job, but it’s not quite complete.” She invited me to her community on the Peru-Colombia border. A Brazilian spiritualist who healed through a water spirit, she emphasized the importance of the mythical and spiritual in indigenous communities. She taught me a dolphin invocation song.

In the morning, when I practiced the song, many dolphins appeared. I felt a bit afraid, like I was playing with things I did not understand. As a result, I decided never to do it again, out of respect for the area’s beliefs and cosmogonies. I constantly balance integrating cultural knowledge with my scientific biological understanding.

A profound connection with Pink River Dolphins: advocating for conservation

Sometimes, I look back and question whether things have improved. I usually say I am 51 percent optimistic, which means I am 49 percent pessimistic. The dolphins live in a region with too many interests and rapid changes that go unnoticed. The indigenous world of the Amazon, as we imagine it, has changed.

Large emerging cities and organized crime operate in the region, spanning all countries. These forces drive illegal mining, deforestation, and the trafficking of cocaine, wildlife, and timber. Mercury pollution, overfishing, and deforestation cause serious climate imbalances, with the dolphin as yet another example of the negative consequences.

Last year, the water temperature reached 40 degrees Celsius, an unprecedented event. In the Colombian Amazon, I heard of hundreds of dolphins dying in Brazil. Dolphins also began to die in my area. The pain of realizing my intense work is not enough to save them feels enormous. My deep connection with dolphins serves as a tool to address the conservation of great rivers.

Our efforts focus not just on conserving dolphins but on preserving the great wetlands and rivers for everyone’s benefit. This includes the people living there and the diverse species sharing these waters. At 56, colleagues often ask how long I will continue fieldwork. They suggest I delegate, but I need to be on the frontline. It keeps me alive and passionate. Staying in cities and attending bureaucratic meetings would cause me to give up. After so many years of watching dolphins, I still feel deeply moved by them.