Argentinian man recalls ‘Pasapalabra’ game show world championship win

In each little free moment—on busses, in my dressing room before a recording began or at home before sleeping at night—I referenced my spreadsheet of words and definitions. It gave me confidence, but I also noticed that luck seemed to work in a particular way as well; more than once, they asked me about a word that I read for the first time just that day or the day before.

- 4 years ago

June 2, 2022

BUENOS AIRES, Argentina—I had only one word left to complete the circle and become the world champion of “Pasapalabra” (The Alphabet Game) in Chile. I already knew what it was. I only had five seconds left on the clock, and I could not wait for it any longer.

When the host, Julián Elfenbein, said the letter V, I let fly: I said “Vasera,” and as soon as the letter on the monitor changed from orange to green, I knew for sure I had won.

In front and behind me, the public erupted into cheers. To my left, Julián was also celebrating, as was the cameramen and technicians. The real surprise was my competitor, the Uruguayan Inti Lenina. Suddenly, I was in his arms. He was celebrating my triumph even more happily than I was.

The program ended, and I called my children. It was recorded a couple of days before it aired, so I didn’t tell them I had won. I just told them to make sure to see it, that I sent them my regards. For me, it was more exciting than they saw the step by step than simply telling them the result.

When they saw it with their mother, they called to congratulate me. I was already back in Argentina and had just returned home after work. Normal life resumed its course, but there I was as if I had been declared the world champion all over again.

A bad first experience followed by a second chance

A little over two years ago, my partner signed me up to compete on “Pasapalabra.” She saw it every day, and occasionally we watched it together. Sometimes, I would throw out some answers from my armchair; the participants seemed to have more trouble. That convinced her that I would do fine if I were to compete.

I was not convinced, but I was having a terrible financial time and the show, apart from being a fun game, was a chance to win some money.

I went to the first casting without preparation, and it went so badly. On the show, the circle is a wheel with all the letters of the alphabet; for each of them, contestants must decipher a word that starts with that letter. Usually, the clue is its definition in the dictionary.

The casting test consisted of two circles, and in both of them, I only guessed a few words well.

I left there with wounded pride. When I play, I’m serious, so that sparked my competitive spirit. I prepared myself to go back: I opened an Excel spreadsheet and started inputting words and their definitions. Hundreds, thousands, tens of thousands. Currently, that file has more than 35,000 words, although I must have only studied half.

The show’s production gave me a second chance, and I have been grateful to them ever since. Nothing that came after would have happened without that extra chance.

Support, studying and a bit of luck lead to winning streak

Once I started competing on the show, I kept winning, so I had to come back again and again. Suddenly my routine included my Excel spreadsheet study sessions and three or four tapings in the television studio per week.

I work preparing internal reports for an oil company and also study systems engineering. Though I gave up my university studies for a while, my job allowed me to change shifts, modify my rest days and combine schedules with other colleagues so as not to miss the show and stay employed. Those were exhausting days: leaving a shooting, going to work, arriving home at night, and shooting again the next morning.

Winning “Pasapalabra” involves monetary rewards, so little by little my financial situation improved. At the same time, my drive to keep playing grew stronger. Everything about it was fun: the game, the interaction with the local host, Iván de Pineda, meeting other participants, dealing with the channel’s technical team. I also enjoyed seeing the show’s impact; people who don’t know me get happy for me. It is weird but very nice.

In each little free moment—on busses, in my dressing room before a recording began or at home before sleeping at night—I referenced my spreadsheet of words and definitions. It gave me confidence, but I also noticed that luck seemed to work in a particular way as well; more than once, they asked me about a word that I read for the first time just that day or the day before.

I played 46 circles in a row until the channel discontinued the show. Luckily, another bought it, and I won another 53 times there. In the last one, I was able to complete the entire thread with correct answers, which won me a significant accumulated prize.

Competing in the ‘Pasapalabra’ World Cup

That win marked the end of my participation because when a contestant completes an entire wheel, they leave and new competitors get a chance to compete.

I would not change having won, not at all, but I did have a melancholy feeling when that daily life with the show wrapped up. I missed the tapings and never stopped preparing, studying definitions and words, and adding material to my study sheet.

When I found out the same show carried on in Chile, I signed up to participate. I didn’t think too much about the future; the logistics of playing in another country can be inconvenient, but I only thought of satisfying my desire to continue being linked to this competition. If things went as well as in Argentina and I ended up having to tape episodes several times a week, I would find a solution.

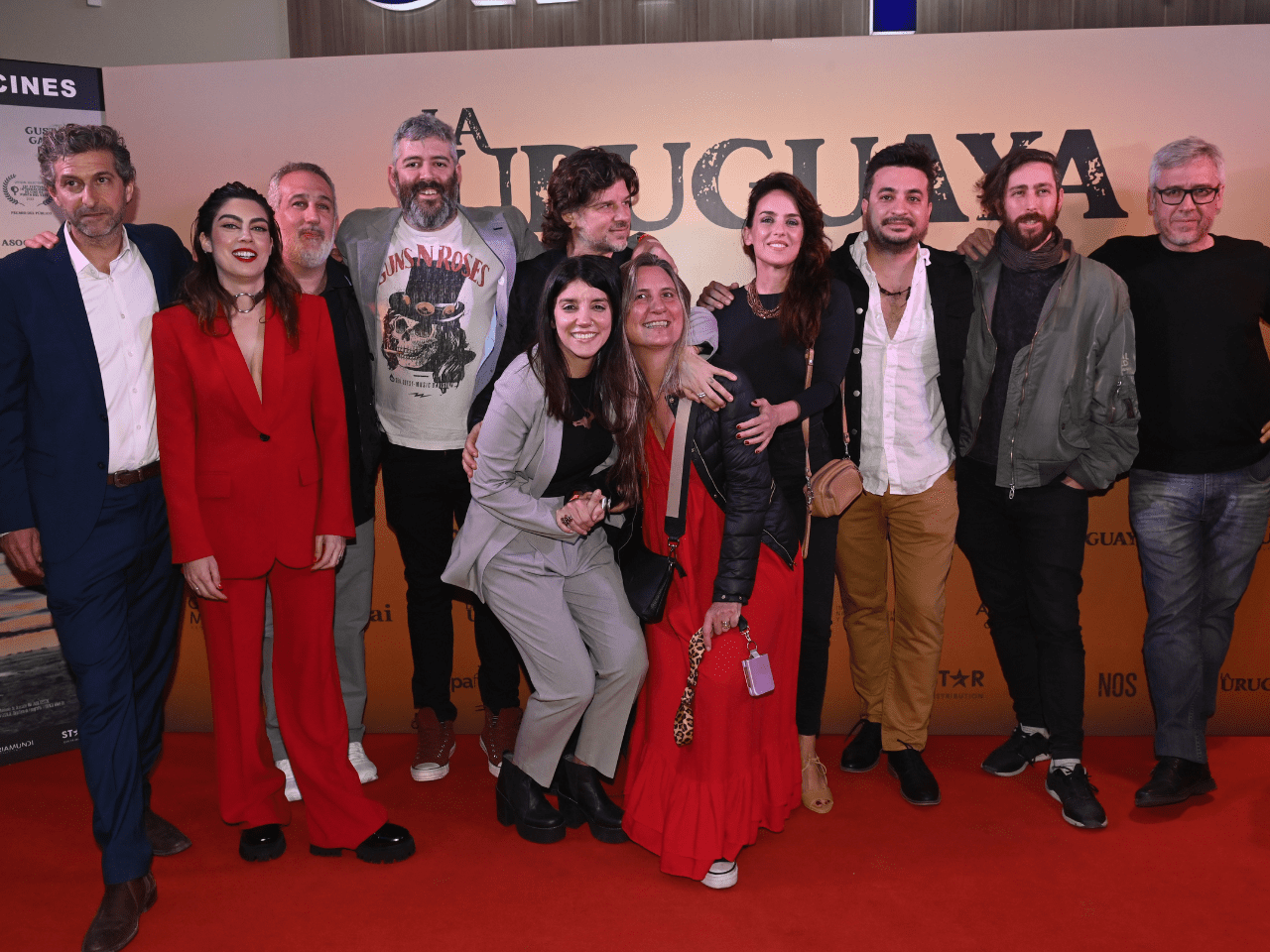

At that precise moment, without my knowing it, the Chilean production was organizing the “Pasapalabra” World Cup. They summoned me for that new contest.

In Chile, I was able to take advantage of everything I learned along the way. Some people know much more than me, but for some reason, they couldn’t beat me. It’s not just about knowing the words; you must also remember and say them on time, keep an eye on the clock, and play with what happens to your opponent.

Little by little, I was able to pay attention to more aspects of the game.

At first, I only listened to the word that came next and focused very hard on that. Then, I was able to retain pending words; to answer them in a second or third round while still listening to the following ones. Later on, I was also able to see what degree of difficulty my rival had ahead of me, to know how much room I had left to risk or if I should be more conservative.

In the midst of all that, I learned to interact with the host, respond to his jokes and return other jokes, all without losing my focus.

Preparing for what comes next

Since I became a world champion, I have not stopped giving interviews, and people greet me on the street. Though I’m still not used to the attention and I don’t seek it out, I do like it. I imagine that everything will calm down soon.

I think about what to do with everything I learned. My vocabulary is much richer, although for now I only use it to laugh with friends, throwing out weird words in the middle of conversations.

I want to keep playing this, to keep experiencing this adrenaline rush that I can’t find anywhere else. Just in case, before any possibility that may arise, I keep reading. I grab a batch of two hundred words and study them, the next day I review them, then jump to new ones or revise a batch I read a while ago.

I want to keep up the pace and be ready for whatever comes.