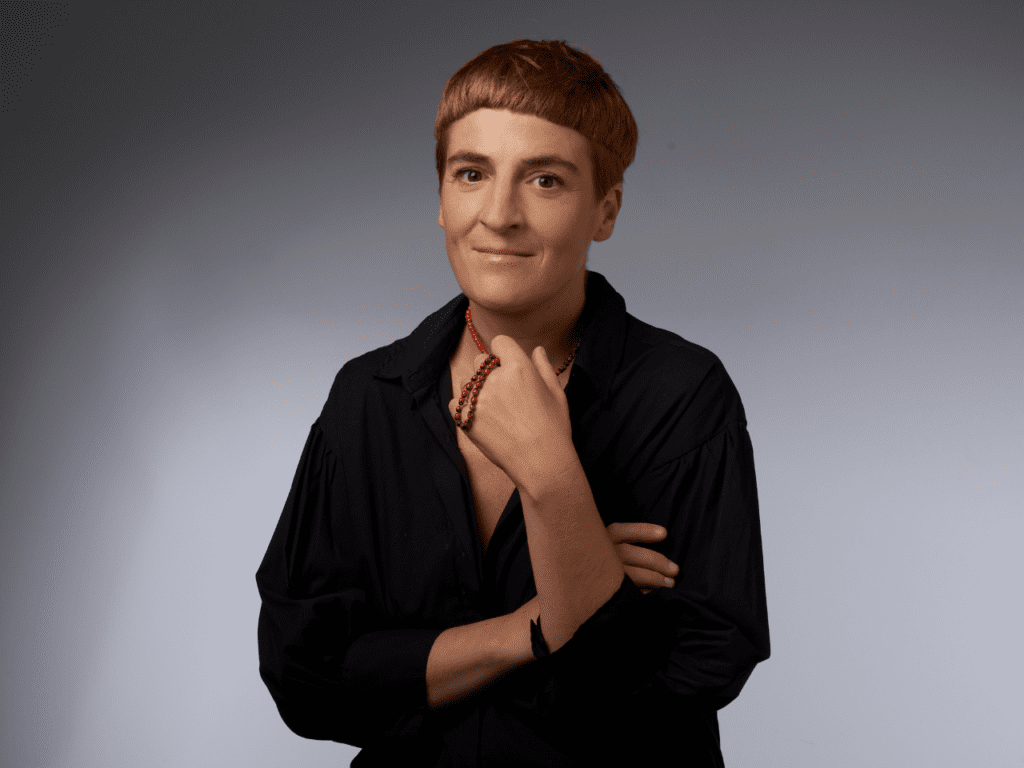

Intersex advocate shares journey, highlighting dangers of non-consensual surgeries

I was born with congenital adrenal hyperplasia, a condition affecting the development of my external genitalia. I am an intersex individual, although back in 1981, doctors and society had limited understanding of such matters.

- 3 years ago

August 17, 2023

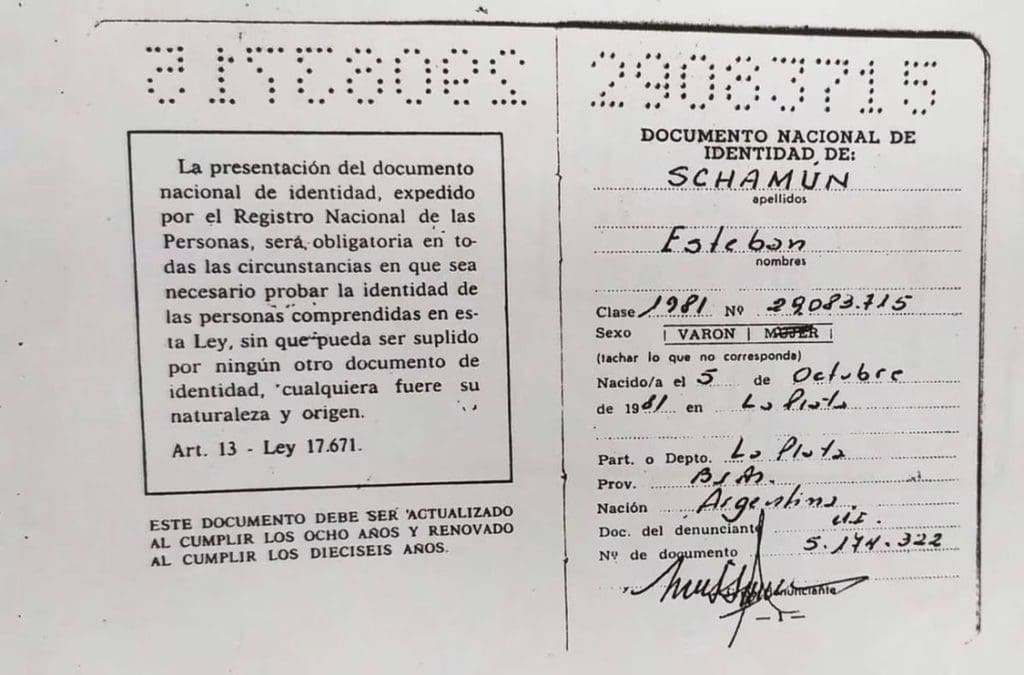

LA PLATA, Argentina — As the evening deepened into darkness, I readied for a party with friends. Like countless times before, I approached my father’s desk and opened a drawer. This time, a green folder labeled “Candelaria – Salud” seized my attention. Inside, a birth certificate lay before me with a hidden truth: I had been born Esteban, a revelation concealed for 17 years.

I stood in a stupor while questions overwhelmed me. I felt my life had remained concealed, casting me into absolute darkness. Irreversible change swept over everything. The news weighed heavily on me, prompting withdrawal from friends and strained interactions with my mother. The name Esteban became an irritant, evoking a sense of disgust when heard. Regrettably, sharing the truth with others felt impossible, leaving me isolated.

Read more non-binary stories at Orato World Media

Medical journey begins, earliest procedures shrouded in secrecy

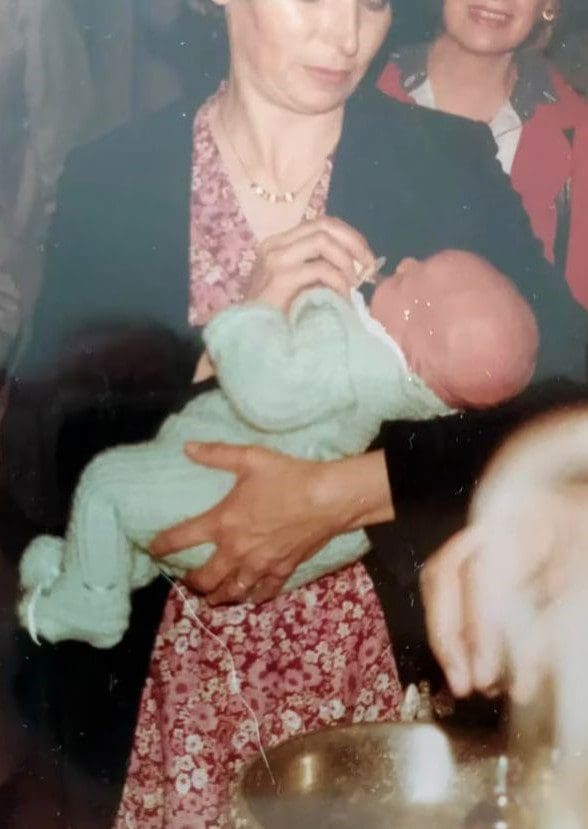

I was born with congenital adrenal hyperplasia, a condition affecting the development of my external genitalia. I am an intersex individual, although back in 1981, doctors and society had limited understanding of such matters. Doctors initially identified me as male when they mistook my developed clitoris for a penis, marking the beginning of a series of surgical interventions.

My childhood overflowed with happiness, never confined to the limits of four walls. I explored and experienced the world around me. I relied on lifelong medication, but at the time, I believed it solely addressed a kidney issue. That’s the information I conveyed to anyone who inquired. I wasn’t being deceptive; my knowledge failed to extend beyond those details.

The earliest surgeries remain blur in my memory. However, one moment stands out, a study involving two blood samples, one at rest and the other after an hour of walking. My dad devised a plan to keep me at ease. He promised to buy me a pack of stickers from every kiosk we walked by. Thankfully, what could have been an overwhelming experience, turned into a joyful moment filled with pure fun.

With irreparable damage, I merely endured the suffering

As a 12-year-old, I recall another surgery on my genitalia. A medical team inserted a catheter for urine passage, causing intense pain. The discomfort increased over time. I voiced my complaints persistently until a nurse abruptly removed the catheter.

The sudden motion triggered an indescribable ache like an internal burning sensation. The accumulated urine flowed out, along with latex gloves inadvertently left in the vaginal canal to prevent the incision from closing. Witnessing and experiencing all of this left me profoundly shocked. To this day, I recall the scent of the room, the position of my body, and the excruciating agony induced by the procedure. The purpose behind their actions eluded me. I merely endured the suffering.

I never had anyone to confide in about it. Gradually, I realized the need to guard my secret. Relatives from various cities visited, but none were aware of the surgeries I underwent. No one asked, and my parents remained silent. The accumulation of secrets formed an immense barrier around me. It was an era when discussions remained limited, actions spoke louder, and silence prevailed. I could not discuss intersex.

At seventeen one final surgery took place, anger becomes my coping mechanism

From an early age, I knew I was a lesbian. Revealing this truth seemed impossible., let alone confessing I had been assigned male at birth and undergone multiple surgeries on my genitals. Each day felt like a haze, a continuous state of confusion and uncertainty, as if a persistent buzz surrounded me, leaving me lost to navigate reality alone. I didn’t know anyone who had gone through a similar experience.

In contrast to my childhood, trauma significantly impacted my adolescence. The same year I found the green folder at 17, one final surgery took place to address the urinary incontinence I experienced due to the prior procedure. An enormous rage engulfed me, directed toward the world, especially my parents. When my father passed away, I wished the same for my mother. Anger helped me to cope with the weight of a secret I could not understand.

Close to 10 years later, I turned to psychoanalysis. Through these sessions, I began assembling the pieces of my puzzle, weaving my story to confront my mother. I disclosed my discoveries and sought explanations from her, a crucial step in my healing process.

Intersex person breaks silence, speaks freely at Women’s Meeting

Soon after, I understood why my parents kept the truth hidden. In 1981, when I was born, they faced an unfamiliar situation and an entirely new diagnosis. They worked tirelessly to ensure my well-being and the best possible life. Their goal was not deceit, but rather my protection, driven by their imperfect love.

A pivotal moment arose during the 2019 Plurinational Meeting of Women in La Plata, altering my path forever. Publicly addressing an audience for the first time, I participated in an inaugural workshop for intersex individuals. Despite my nerves, I felt determined. The atmosphere offered refuge from skepticism, allowing me to share my story openly. Hearing similar experiences from others liberated me, dissolving my anger and restoring my spirit. Connecting with their stories shifted my perspective, empowering me to speak freely.

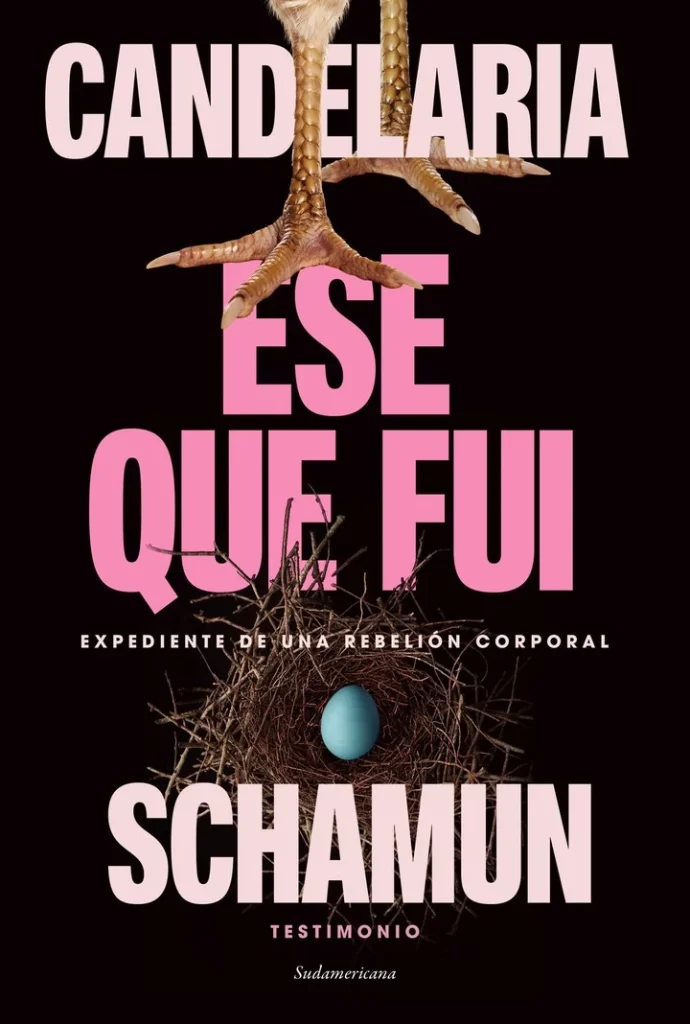

Afterward, I confided in those closest to me and began writing my book. Initially using the pseudonym Vera, which symbolized my quest for truth, I penned the narrative as if discussing someone else. Over time, my mother lost her battle with Alzheimer’s. In her final moments, she saw me as a man. While initially shocking, I soon realized it was her way of reconciling with the past. This revelation brought me peace, aligned with my ongoing writing journey and love for my story.

Intersex advocate shares story to prevent similar struggles

I gradually embraced Esteban as a core part of my identity. Today, I proudly acknowledge his existence. I wrote my story under my real name, leaving the pseudonym behind. This process unfolded calmly, free from anger. I composed the book with clarity and love, aiming to heal and repair my relationship with my parents.

Eventually, I reclaimed and reconnection with 90 percent of my body. The other 10 percent still feel distant to me, due to past trauma. Post-traumatic shock still affects me, manifesting in parts of my life I cannot access or allow others to reach. My body underwent interventions to fit societal norms, causing irreparable harm. This bodily estrangement is a result of being confined to the male-female binary, leaving intersex individuals cast aside.

Sharing my story aims to prevent others from facing similar struggles. It’s a voice for parents in similar situations, highlighting their tenderness and vulnerability. It remains about embracing our imperfections. After my first interview about the book, an older woman reached out. She found solace in hearing someone voice her experiences. If my words can ease others’ silence, every risk was worthwhile. I hope readers find light and peace. Perhaps my pain and sacrifice can bring comfort to others.