He travels the most dangerous sea to save shipwrecked migrants

Among the rescued victims, we encountered a five-month-old baby and a pregnant woman. Relief swept through my body seeing them alive and well.

- 2 years ago

October 19, 2023

BARCELONA, Spain — In 2015, amidst the European migrant crisis, I joined Open Arms, an organization in Barcelona founded by activist Óscar Camps to coordinate rescue missions. At 36 years old, I longed to be a lifeguard and dreamed of saving people. In September 2016, I left for the Greek island of Lesbos where the NGO initially operated, and I witnessed some of the most gut-wrenching moments of my life.

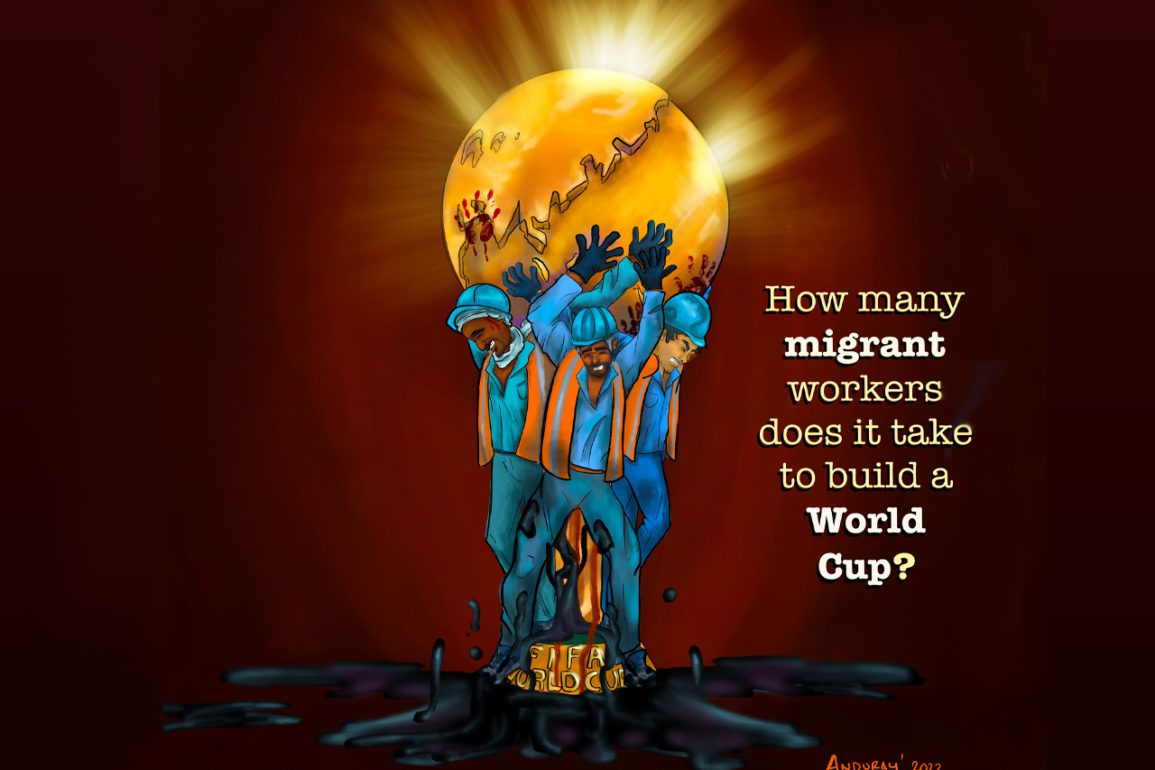

Every year, migrants die crossing the Mediterranean Sea. Fleeing from the dangers of their home countries, the set out in the hopes of starting over. These human beings who face dictatorships, armed conflict, and environmental disasters that destroy their homes look for a better life.

My heart broke as authorities counted the bodies of thousands of dead people. For some, the risky journey to Europe landed them at the bottom of the sea – never experiencing the chance to be free.

Read more migrant stories from Orato World Media.

Patrols often happened late at night, rescuing scared families from the icy waters

Open Arms began its rescue missions on the northern coast of Lesbos in Greece. The first time I joined a rescue, we swam without equipment to the boats. We quickly assessed the situation and helped the passengers to safety.

Gradually, people started hearing about our work and donations flooded in. With a new source of income, we purchased jet skis, boats, and supplies. In four months of 2016, Open Arms saved 15,000 lives and the media touted our achievements. In the early months of 2017, we saved 6,000 more. Since inception, Open Arms has rescued more than 67,000 migrants fleeing for a better life.

I watched in awe as the organization evolved, adding permanent staff, captains, engine officers, sailors to drive the rescue speedboats, and a cultural mediator. The volunteers emerged in mass and soon we found ourselves with doctors, cooks, nurses, rescuers, and journalists, who rotate schedules every three weeks.

On top of the rescues, we face factors outside of our control, like intense weather conditions and the reactions of migrants when they spot us. Time and again, the missions become intense, requiring our teams to adhere to strict protocols for everyone’s safety. When we finally locate a boat in distress, we scan the area, assessing all the pathways in and out.

Through our translator, we identify ourselves as a rescue team. From the moment we embark, we rush to put life jackets on the migrants. Our hearts pound in our chests as we race against the clock. Often, the people we seek to save become agitated and consumed by fear. When they begin to scream, we warn them, further chaos can make their boat move further from us.

Unfortunately, we don’t always make it there in time

Once we gain control and everyone looks secure, we start letting people onto our rescue vessel. A standby boat floats nearby, full of all the equipment we might need. As the migrants make it onto our ship, a string of nurses and doctors check their health. We hand out food, blankets, water, and bracelets to identify each person.

Sometimes, the shipwrecks present imminent danger. If a gasoline line breaks and chemicals flood the salt water in the ocean, fluids mix together generating an odorless solution that can burn the skin. Some victims climb onto our vessel with severe burns across their entire bodies. As we treat their urgent health needs, we have to remind them constantly, we are here to help. Sometimes they fear us, nervously worrying about where they will be taken.

During our last mission near the Italian island of Lampedusa, we spotted a metal boat sinking in the waters. We sprang into action, giving everyone a vest and saving those already in the water – some of whom struggled under the weight of the boat. Adrenaline coursed through my body as we pulled people to safety.

Among the rescued victims, we encountered a five-month-old baby and a pregnant woman. Relief swept through my body seeing them alive and well. When we re-entered the water, we noticed another shipwreck a few meters away. Sadly, a lifeless body floated beside it. Pulling the dead from the water is an excruciating part of this work. It seems impossible to fight off the guilt, wishing we had arrived sooner.

There’s only so much we can do; the State must take responsibility

Following an agreement between the European Union and Turkey which closed the Balkan route, we saw an increase in the flow of migrants through the Mediterranean Sea. As the most dangerous route they face, Open Arms activists now call it the biggest mass grave on the planet.

According to figures from the Missing Migrants Project, nearly 30,000 people have disappeared in the Mediterranean Sea since 2014. Many migrants we encounter have suffered sexual, physical, and psychological violence throughout their trip. We denounce the negligence of authorities in this humanitarian crisis.

On June 13, 2023, a ship sank in Greece carrying about 750 people. Only 104 survived. Our team was on assignment that day, but the coverage area was larger than the entire country of Germany. We knew the coast guard and Greek government were aware of the of the vessel hours before it sank and it did nothing. [The New York Times stated that Greece treated the incident like a “law enforcement operation, not a rescue.”]

I often think of the more than 600 innocent people who ultimately met their end at sea. In their final moments, did they hope for someone to save them? This job never gets easier and at times, the weight of responsibility feels overwhelming. Each and every person we meet has a story and those stories stay with us forever.

Whether facing dictatorships, wars, or insurmountable challenges back home – these people climb onto fragile boats to make their way to other countries for the slim chance of a better life. They float out onto the dangerous sea where uncertainty meets them. Some make it, but many die along the way. My job – to save as many people as I can from this tragic reality – means everything to me.