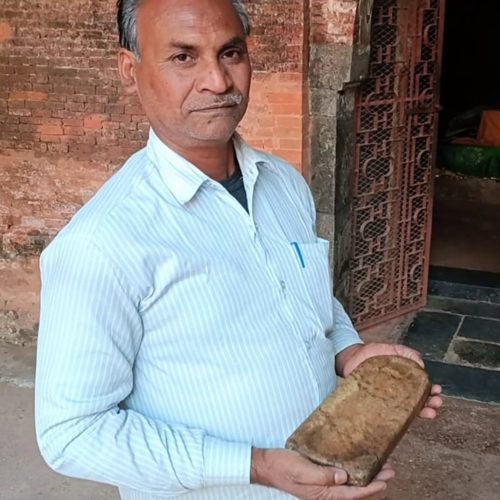

Third generation Khadim in India guards sacred footprint from dusk to dawn

When I arrive in the morning, I take the sacred footprint and mount it on a marble pedestal with the same fervor for religion as my predecessors. I light incense, sprinkle rose water, and rub perfume on the tablet, before performing the traditional Dua-e-Fathia prayer. Then I open the doors of the mosque for visitors.

- 3 years ago

October 27, 2022

WEST BENGAL, India ꟷ At 9:30 a.m., I begin my daily routine of carefully transporting the sacred and precious “Footprint of Prophet Hazrat Muhammad.” As a third generation Khadim [a servant or attendant] of the Qadam Rasul Mosque in Gour, West Bengal, I began my work in 2010. I transport the footprint, etched on a stone table, by bicycle from my home to the mosque every day.

The ride extends six kilometers or 3.7 miles. I cannot describe the absolute blessing of carrying the revered footprint of the prophet, also known as Qadam Rasul. The mosque itself remains under the protection of the Archeological Survey of India (ASI).

Sacred footprint susceptible to theft, guarded by family for three generations

The Khadims of Mehdipur – a small hamlet in Malda – have guarded and carried the sacred stone tablet between dusk and dawn for eight decades. Eighty years ago, miscreants stole the sacred treasure. In total, it was stolen three times.

Click here for more Arts & Cultural stories from Orato World Media.

After the first offense, the thieves buried the tablet in a nearby pond, hidden beneath a pile of water hyacinth. On the second occasion, they threw it into a deep well; and on the third, it was hidden inside the mosque itself. History tells that the Khadims mysteriously retrieved the tablet with the help of a trance.

My grandfather Jinnat Hussein Molla served as the mosque’s Khadim at that time and maintained security. He brought the theft to the attention of ASI, which served as the nation’s top organization for archaeological research and cultural asset conservation. In what seemed like a strange decision, ASI asked my grandfather to provide maintenance and protection for this rich piece of cultural and religious history.

Since then, my family has protected the tablet at our home. We commit our entire lives to serving the prophet. We passed this responsibility from my grandfather to my father Jiyaruddin Molla. Now the task falls to me.

Khadim wishes he had more support for the care of the ancient relic

I wake up early in the morning to complete my Namaz [Islamic worship or prayer]. Then I bring the stone table to the mosque at 9:30 a.m. I stay at the mosque for at least seven hours before returning home. I protect the valuable holy gift at all times, securely storing it on a bunk in my home.

With very little funding or support, I keep the priceless tablet in an old leather pouch. Faulty storage and maintenance led to the white marble surface progressively deteriorating. It should be stored in a wooden box.

During the rainy season, the unpaved roads I traverse every day turn muddy and slippery. I fear stumbling and damaging the tablet. Even if that extends my travel time, I cycle carefully and slowly. I also worry about the security of the tablet in my home.

My family never received compensation for protecting the artifact; we offer the service free of charge. However, as long as I am alive, I will continue my work. Serving God amidst billions of people makes me the happiest person on earth.

[The journalist for this story contacted the Superintendent of the Archeological Survey of India for the Raiganj Range, Hari Om. Om first asserted the mosque “is not an ASI-protected site.” After speaking with his subordinate, he modified his statement and said, “it is an ASI-protected monument, but ASI has no influence on the care of Qadam Rasul.”]

Khadim performs daily rituals, welcomes thousands of visitors from around the world

As a Khadim of the 491-year-old mosque, I see over 100 worshippers congregate daily to offer prayer to the prophet’s footprint. Tourists arrive from throughout India and beyond. I see American, Swedish, Malaysian, and Swiss people.

When I arrive in the morning, I take the sacred footprint and mount it on a marble pedestal with the same fervor for religion as my predecessors. I light incense, sprinkle rose water, and rub perfume on the tablet, before performing the traditional Dua-e-Fathia prayer. Then I open the doors of the mosque for visitors.

Read more stories out of India from Orato World Media.

I devote seven hours a day guarding the sacred object inside the mosque. I change the chadar on the podium (a ceremonial fabric showcasing sacred text), and sweep the mosque inside and out to keep it spotless.

Locals come to perform their daily Namaz and leave, but visitors have many questions. I have to play the role of tourist guide, offering positive replies and information. They often place a small donation on the pedestal. We use the money from donations to commemorate Eid and other festivals.

During Maulid Al-Nabi on the twelfth day of the Arabic month Rabi al-Awwal, we present a spectacular commemoration of the prophet’s birthday. About 5,000 worshippers visit that day. We celebrate Fatiha Dua, Eid-Ul-Fitr, and Eid-Al-Adha.

Reports say over 71 footmarks were etched in the ground after the prophet returned from his meeting with Allah in the cave of Hira. Ours is an original footprint.

Tablet travels through countries and decades to reach its final destination

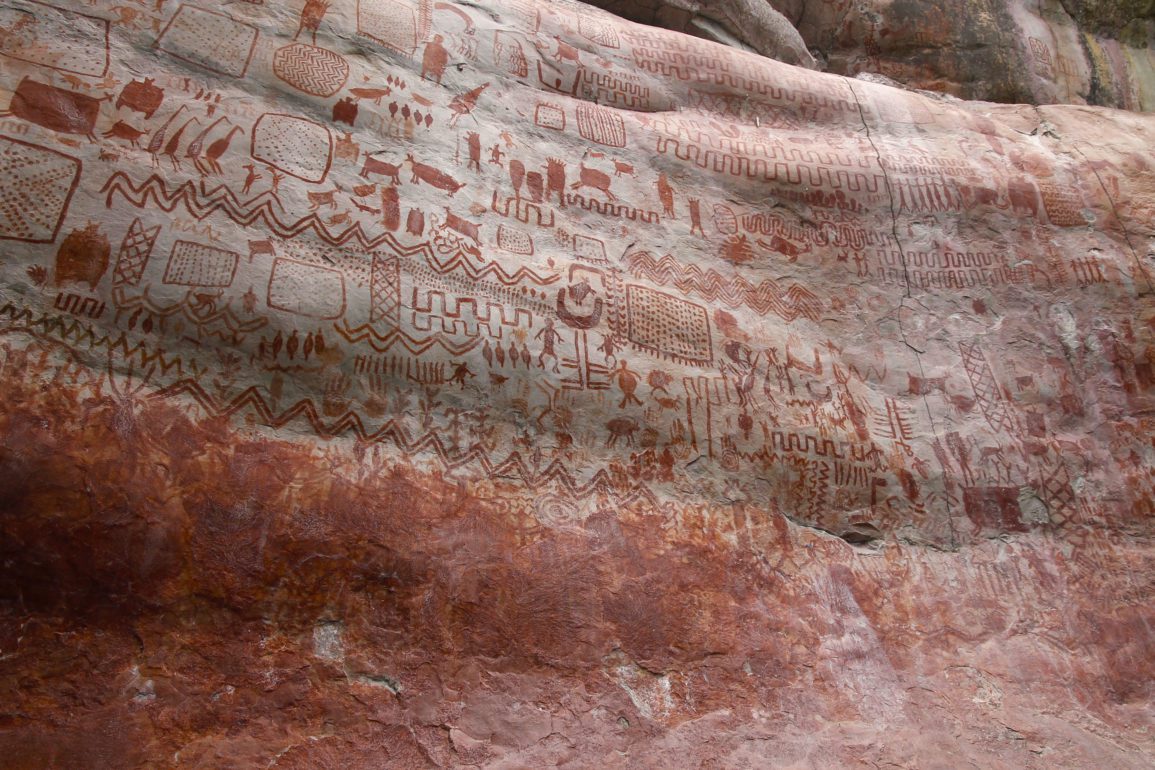

In the early thirteenth century, the Sultanate of Arabia gifted the tablet to an Iranian Sufi saint named Abult Qasim Jalaluddin Tabrizi. Tabrizi traveled from Mecca, Saudi Arabia with the marble tablet. He arrived in Pandua, Bengal. Later, a Bengal sultan named Alaudddin Husain Shah discovered the tablet in Tabrizi’s meditation room and relocated it to Gour.

Eventually, the sultan Nasiruddin Nasrat Shah built a mosque to venerate the artifact. He named the mosque Qadam Rasul. To this day, people recognize the mosque as one of Malda’s most stunning and historical landmarks.

The three-acre archeological complex is home to the mausoleum of Sultan Nasrut Shah, the tomb of Tabrizi, the commander of the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb, and Fateh Khan. A single dome and elaborate stonework create a stunning display. Unexpectedly, the original builders used Hindu Chala architecture, featuring a square interior and a three-sided verandah where the footprint is kept.

According to history, Tabrizi brought the relic to Bengal mainly because the prophet had never visited India. He knew the pilgrims from India could scarcely afford to travel to Mecca for Hajj. At that time, people traveled by sea, on horseback, or on foot.

The right footprint of the prophet – which measures 11 to 12 inches in length – only left Gour one time. The first Nawab of Bengal, Murshid Quli Khan, moved it to his headquarters in modern-day West Bengal. One night another Nawab, Siraj-ud-Daulah, dreamt that the holy artifact belonged to Gour. He ordered it to be returned but it did not make it back to Gour for forty more years, after the death of Siraj.

Tailoring clothes at night to earn a living

The mosque serves as a place of devotion and meditation. I could simply sit here for hours. I feel euphoric from the exquisite sensation, as the aroma of incense and loban waft through the sanctum sanctorum. In all my years, I never experienced an unpleasant incident.

I see people arrive 365 days per year from all walks of life, facing multiple issues. I say leave your anxieties aside, because God will take care of everything. After paying their respects, they leave, but often return. They find comfort and calm; this is what we call faith.

Back home, I live with my wife and son in an 80-square-foot, tiled-roof house in Mahdipur. Of my three children, two of my daughters married. I earn my livelihood through my tailoring business, stitching ripped garments and making new clothes. When I come home from the mosque around 4:30 p.m., I sit down and begin to work.

Whether rain or shine, I will continue to be of service and perform my household duties when I come arrive in the evening. If I do not carry out my responsibilities, officials could close the doors of the mosque. Aside from me, only two guards sit duty in Gour, which has 16 monuments. Gour boasts significant historical and tourism significance for both Islamic and Hindu traditions. Unless something changes, my son will carry on the work when I no longer can.