Surfing champ raises red flag on ocean spill: millions of tiny plastic pellets littered beaches in Spain

The spilled cargo floated to shore like a great white tide. The small pellets broke against the stones and spread across the sand… It felt like an environmental catastrophe.

- 2 years ago

February 21, 2024

GALICIA, Spain ꟷ On the seashore, as the waves crashed against the rocks, dozens of white bags appeared, some whole, others broken. Spilling out from the bags, the beach lay covered in thousands of tiny, plastic pellets. It was as if the ocean returned what did not belong there. The beaches in Galicia went on high alert as the tide spread the plastics across [nearly 400 miles of coastline], from Galicia all the way to Basque Country.

A cargo ship called the Toconao, sailing near the Portuguese coast, dropped 26 tons or 1,060 bags of the pellets. It also dropped other containers carrying tires and plastic wrap. [The containers fell off the ship in early December 2023. The pellets washed up on the Spanish coast at the Bay of Biscay. Also called mermaid tears or nurdles, these pellets are melted down to make products like water bottles and shopping bags.]

The spilled cargo floated to shore like a great white tide. The small pellets broke against the stones and spread across the sand. The beach became flooded with plastics, difficult to clean due to their tiny size, weight, and light color. It felt like an environmental catastrophe.

Read more first-person news on the Environment at Orato World Media.

With sadness and fury, hundreds of volunteers struggle to clear the beaches of plastic pellets, one by one

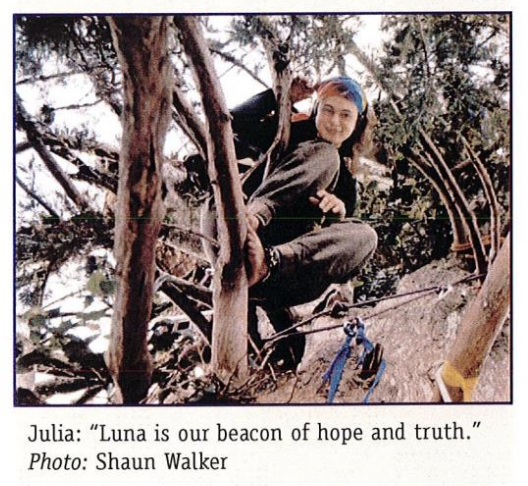

Growing up in a family of lighthouse keepers, I became a doctor. Yet, my life took a turn when I fell in love with surfing. The sport conquered my heart and without expecting to, I became a champion surfer in Spain and a world runner-up. I never imagined as a child becoming an elite surfer, but today all I want is to spend time in the water.

So, on that December morning, when I made my way to the beach from the sea, I saw something truly abnormal. The plastic pellets formed a white blanket that covered everything. A deep sadness and fury consumed me. I felt helpless but decided to release a video on my social media denouncing the spill. My video felt like a desperate cry, and it went viral, mobilizing hundreds of volunteers.

People began sharing the story as they saw masses of the pellets spilled on beaches [all along the coast]. The case went public. The picture in front of us seemed bleak, with mountains of pellets everywhere. It looked like snow scattered across the sand and over the sea. With more than 100 individual beaches affected, we crawled carefully on our knees picking the tiny pellets up by hand.

Hundreds of volunteers, municipal workers, and environmentalists tirelessly moved in unison, some with small shovels or kitchen utensils like strainers. We gazed at each other with confusion in our eyes as we performed the difficult task. For days, we tried everything to eliminate the pellets from our precious beaches, yet nothing proved effective. If you stepped on the pellets, they easily became buried in the sand. Wearing gloves, we tried to help, picking the pellets up one by one for hours, only to gather handfuls. It seemed an impossible task.

Animals and plankton ingest the tiny plastic pellets, affecting the entire marine food chain

The scene felt crazy as wave after wave, the ocean delivered more pellets to the beach. Each tide left me feeling like I accomplished nothing. Frustration set in, then, amidst the chaos and desperation, I came up with an idea. I discovered the bags used to carry diving fins were the perfect size and shape. When shaken, they released the sand but not the pellets.

Although the task felt titanic, I thought, “At least something is working.” Others followed suit. As I researched the pellets, I learned of the danger they present. They work like small magnets, attracting other toxins and absorbing them like a sponge. They become like little toxic bombs. Then, due to their small size, animals like birds, fish, and crustaceans confuse them with fish eggs. If the pellets enter their stomachs they can stop eating and die.

The animals that survive end up with pollutants in their very tissues – including species we eat. Because the pellets fail to decompose, they fragment into plastic particles. Marine plankton ingest them, plankton that serve as the basis of the entire marine food chain.

Two months after the crisis, Galicia, Spain accounts for the collection of a mere 20 percent of these microplastics. Volumes of pellets still need to be collected or are lost at the bottom of the ocean. The authorities in Asturias deployed a special emergency plan to mitigate damage to the environment. They can address the coasts but cannot do anything inland.

We must stop the dumping of pellets into the sea. Pollution by plastics and microplastics remains a serious scenario. They have plagued the planet for years, and this spill returns the focus to solving the urgency of this problem.