Hydrant airplane pilot battles ferocious blaze for weeks, describes devastating scene from the sky

Flying low in the indicated area, I dropped the water stored on the airplane at high speed. The tongues of the fire caressed the belly of the plane. Turbulence shook the aircraft, and I felt my body become one with the machine. A rush of energy overwhelmed me.

- 1 year ago

October 25, 2024

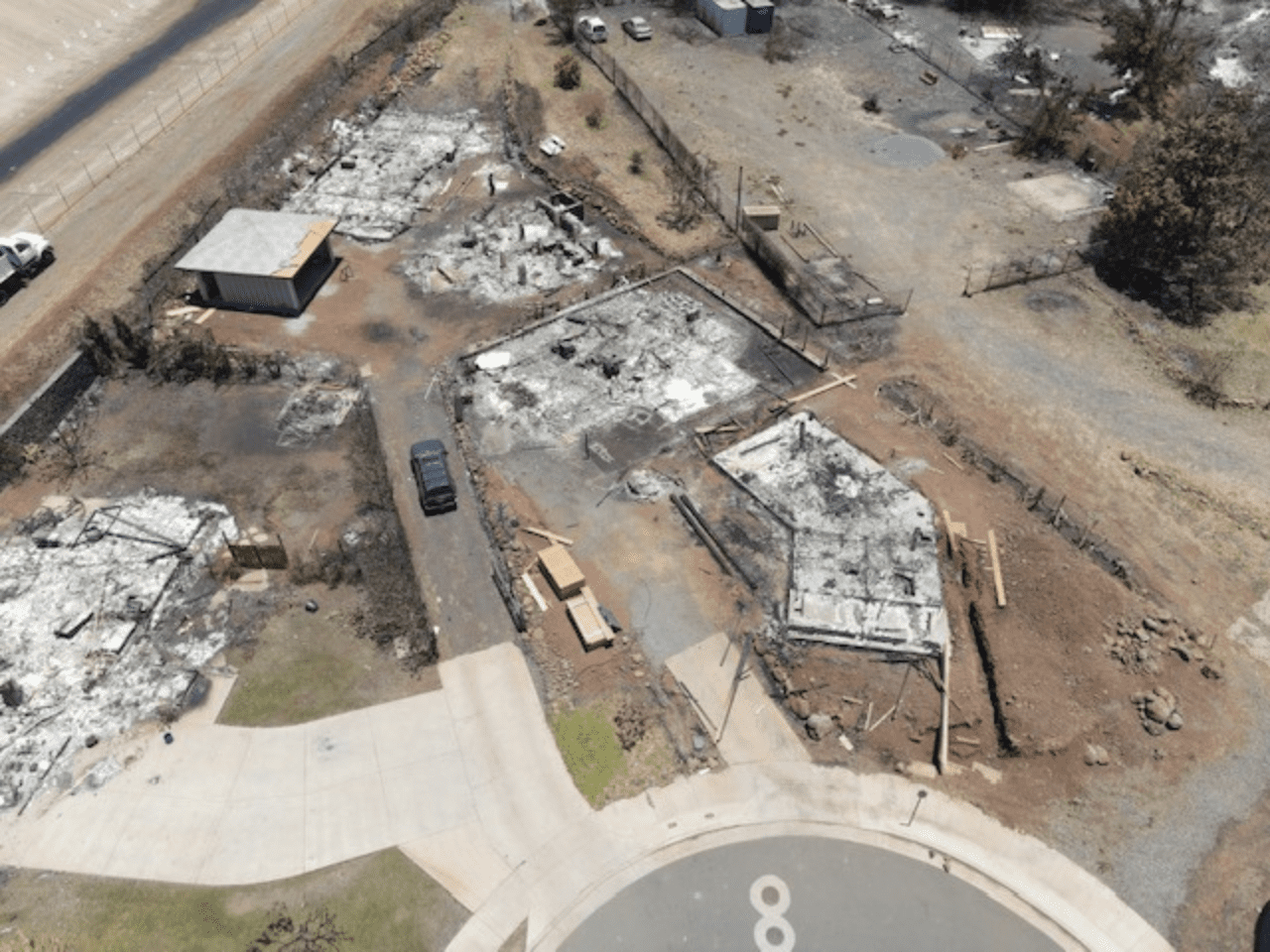

CÓRDOBA, Argentina ꟷ As fire outbreaks multiplied in the province of Córdoba, we went into a state of alert, with several localities classified as catastrophe zones. Flames consumed about 12,000 hectares of land in Calamuchita and another 4,000 in the natural reserve of La Calera. The scene turned into a nightmare as fire ravaged everything, leaving the landscape desolate and dead.

From a young age, I dreamed of flying airplanes, flipping through my father’s magazines and encountering passionate aviation stories. Over the years, I became a pilot and began working for an airline. Later, I trained for catastrophes. When fires broke out in Villa Berna, Intiyaco, and Los Cocos, I joined the firefighters, risking our lives to work the front lines. We fought the flames with no rain in sight.

Read more fire stories at Orato World Media.

Pilot drops water along fire lines to assist those on the ground battling the blaze

On Wednesday, September 18, 2024, a fire started in San Esteban, eventually devouring Capilla del Monte. It climbed relentlessly up the hill in Las Gemelas during the early morning of September 20, then descended back down the other side. This active outbreak followed a wave of fires that started much earlier on September 2 in Villa Yacanto. Within 48 hours, that fire covered 86 kilometers and consumed 12,600 hectares of land.

At the same time, 14 more outbreaks erupted in different parts of the province. Three days later, on Thursday, September 5, a ferocious fire devastated one third of the military natural reserve – 4,000 hectares of preserved national forest. Weather conditions only complicated the situation with wind gusts over 80 kilometers per hour, aggravating and spreading the flames. We felt the urgency. This fire had to be stopped at any cost.

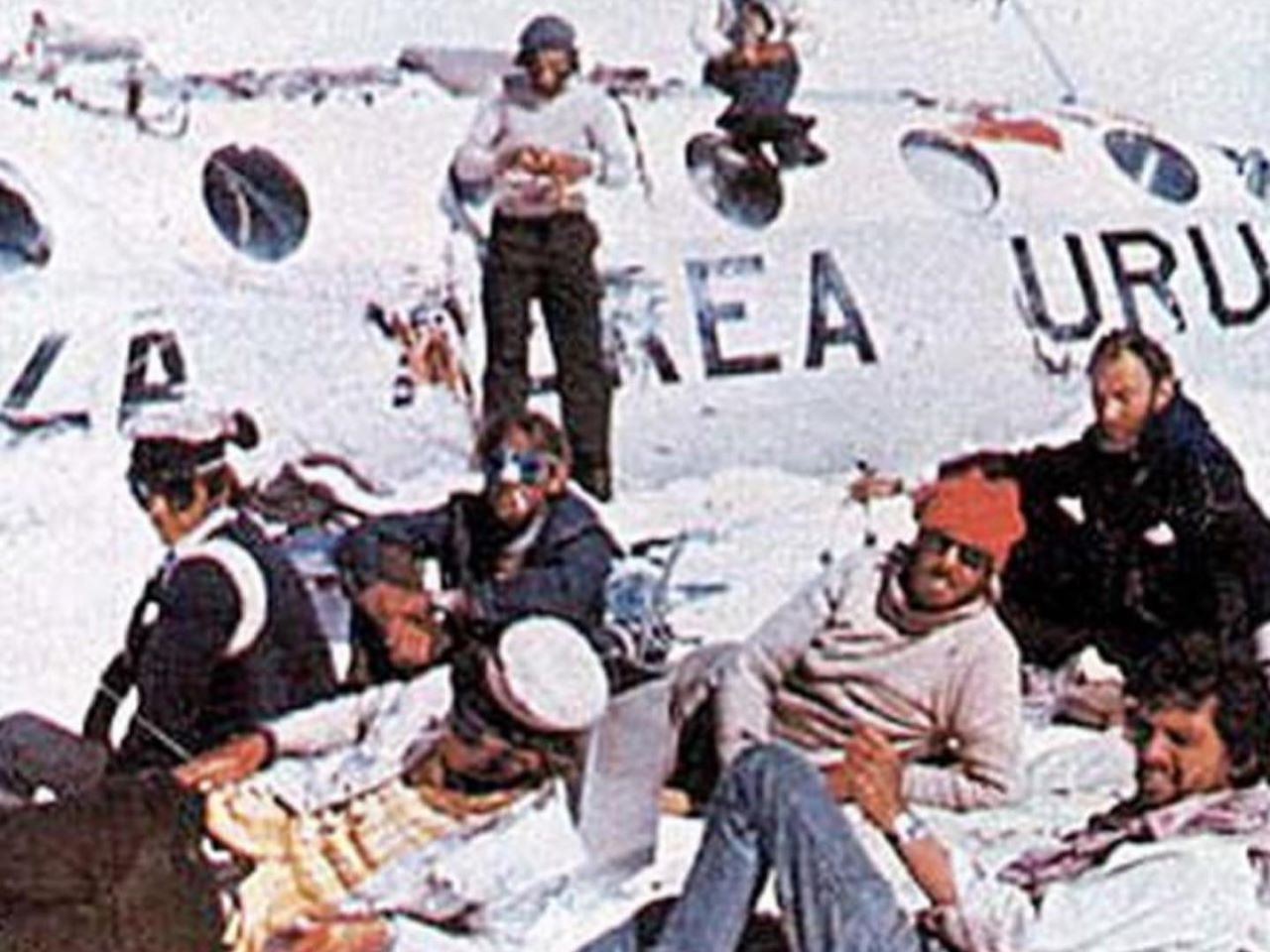

More than seven hydrant planes, six helicopters, and hundreds of firefighters fought the battle without rest. Our main goal was to prevent the flames from reaching urban areas. With unencouraging weather forecasts, we watched as the fire advanced, at times, at one meter per second. Taking turns to rest, we knew we faced a complicated task. Stationed near the front of the fire, my job included supporting the firefighters on the fire line, battling the flames hand-to-hand.

These situations feel very much like war. When the work on the ground becomes complicated or the brigadiers run out of water, we receive orders instructing us on where to drop. From the air, we drop the water on the fire line, then the firefighters complete the next task with machetes or whips to extinguish or control the fire. Sometimes, with a shot, we put the fire out directly. Other times, we don’t even touch it. On this occasion, neither happened.

Trapped in clouds of smoke, pilot searches for the firefighters on the ground

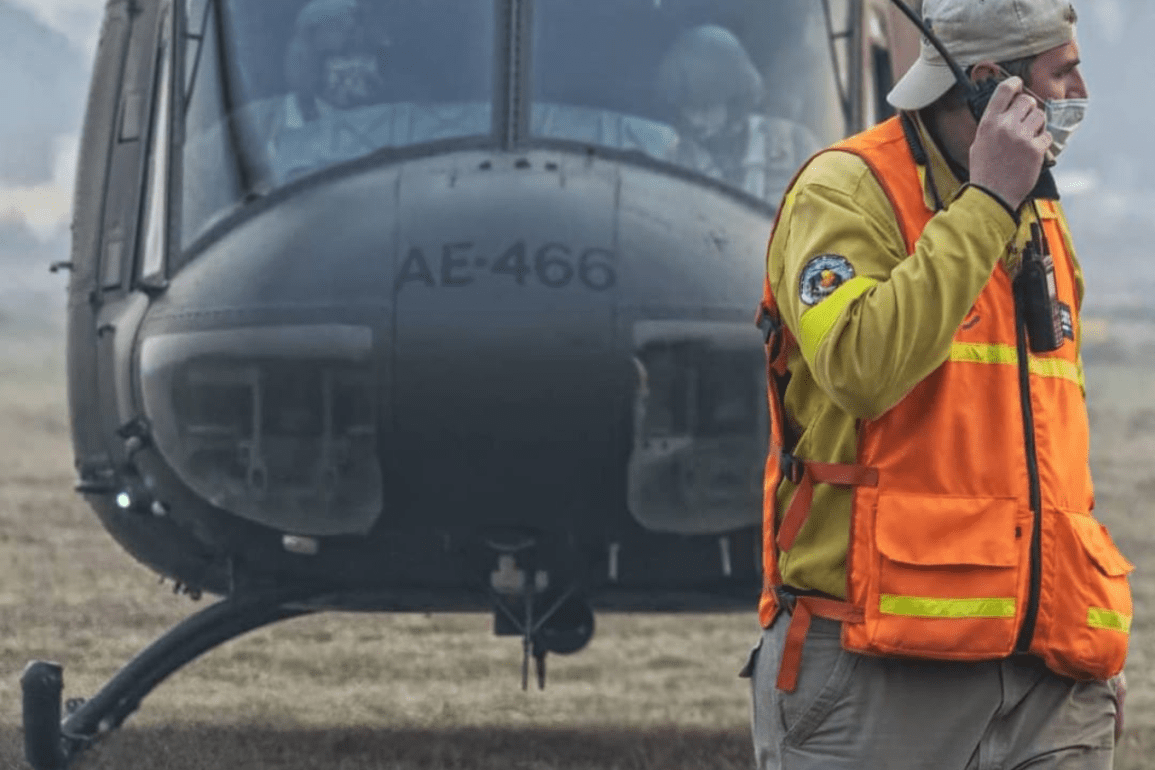

From the first light, I remained on watch next to the plane, loaded with water. I stood ready to take off at any moment. As I waited, I studied the weather, wind conditions, humidity, and temperatures. Several ambulances waited in the area as well. Early in the morning, I communicated with the coordinator, who served as the liaison between the pilots and the ground brigade.

As soon as I received the order, I entered the cockpit of the AT-802, an aircraft used for firefighting and agricultural tasks. I sat in the seat in front of the dashboard – a space no larger than a toilet – where I checked the clocks, buttons, and joystick. Putting on my seatbelt, I spoke in a whisper as I usually do, saying, “I must stop what could be.” Then, with 3,000 liters of water in the belly of the aircraft, I took off. In the air, I avoided the smoke at all costs. Once you enter the smoke, it takes the reigns, and everything becomes cloudy and extremely dangerous.

The magnitude of the fire was so great, visibility remained difficult. The dry, yellow vegetation below, combined with the weather conditions, made them extremely combustible. The slopes of the mountains around Córdoba presented traps and obstacles, often hiding the smoke from view. At one point, I flew into a dark cloud and struggled to get out.

Between me and the firefighters – with whom I remained in constant contact – stood a curtain of smoke. I had to visualize them in my mind. “Where are they,” I asked on the radio. I flew lower and suddenly saw them. The scene looked desolate. Fires destroyed everything in its path as if it swallowed the landscape. I felt beaten, seeing the vegetation and fauna disappear in the wake of the flames.

From the sky, pilot sees the flames closing in on the firefighters

Flying low in the indicated area, I dropped the water stored on the airplane at high speed. The tongues of the fire caressed the belly of the plane. Turbulence shook the aircraft, and I felt my body become one with the machine. A rush of energy overwhelmed me. It was as if the wings of the airplane became my arms, and I felt its power in every part of my body.

I heard a voice over the headphones say, “Left flank.” At that moment, I checked my height because, from very high up, the water can evaporate in seconds from the heat of the fire. I pressed the button, opening a set of covers to perform the water drop. I then dropped more water from the tail. Once we contained the fire on that side, we refocused on the east flank facing town. We needed to get around the fire quickly to prevent spreading. If the fire got out of our control, there would be no turning back.

When considering the cosmic scale of the fire, the plane looks like a little yellow fly circling around. Below, the brigadiers fight the flames. They are the boots on the ground. The radio constantly relays messages as adrenaline kidnaps my body. It feels like living through a scene in a movie. You do not measure success by what happens, but by how much you can save.

As we circled, I saw a group of firefighters in the bush. They could not see that the fire approached them from behind as they battled the fire in front of them. From the air, I witnessed the fire closing in on them. At that moment, another two reinforcement planes arrived.

Moments arise when those battling the fires must retreat

With the flames a few meters away from the firefighters, every second counted. The wind blew hard at more than 80 kilometers per hour. I issued the order for them to run because if the water fell on them, they could be seriously injured or die from the impact. “Run away! The fire is coming,” I shouted. As soon as they reached a few meters away from the drop point, I plummeted at full speed reaching a low flight. I opened the hatch and, together with the other pilots, dropped the water.

Had I been alone, I could not have saved their lives. The firefighters on the ground would have easily been burned by the flames. We turned around and went back to refill before returning to the inferno. For 10 days, we worked tirelessly battling the flames without stopping. The moment the sun rose, we took off and flew until sunset. Though our work ended at nightfall, the firefighters continued working into the night when temperatures dropped and the humidity increased.

I felt feeble before the magnitude of the outbreaks over the ensuing days. At certain moments, I believed we may not stop it. Despair set in as I watched the mega-fires on the surface from my place in the sky. At times, the fire and the wind pressed forward with such ferocity we had to cut out, unable to fly. In those moments, the firefighters retreated in the face of the fire’s relentless advance.

Although you give it your all, sometimes you win and sometimes you lose. Flying above the scene, it looked like hell. Waterspouts, smoke, flames, helicopters, airplanes, brigadiers, houses, and land mix into a devastating spectacle.

Fear becomes useful in the face of the inferno

As atmospheric conditions change rapidly, the shifting temperatures and pressure transmit to the aircraft. You must prepare for a hostile environment. The shifts move the aircraft, and you become part it, like the prelude to a panic attack. As pilots, we live on the edge. You feel the heat of the fire and the jolt when the force of it lifts you up.

At one point, the swirling winds blew the fire out of control in the hot spots and the firefighters needed support. We managed to make 20 turns over a long line of fire that 53 firefighters fought below us. They guided us until we reached the release point. We heard, “Three, two, one, stop!” Minutes later, the smoke blinded me. I jumped from a ravine; uncertain I would make it out. Fear gripped me and the plane was out of control.

With the soul of a cowboy, I learned to fly through mountainous, twisting landscapes. So, I took a sharp right. I entered an air current that flowed like a river and let myself go, escaping the chaos. Fear is my friend. The day I lose my fear, I need to stop working. Being unaware of risk leads to mistakes, and heroes are useless. Each of us has a mission to complete; teamwork and trust remain imperative when time is scarce.

After several weeks, we extinguished all the fires in the sierras. Now, the situation is calm as we guard for ash. Embers remain hot, and if the wind picks up, they can burn. Rain will be a welcome relief. In the aftermath of these battles, people offer us gifts, hugs, and drawings from their children. They call us angels and move us to tears. From the first day I dedicated myself to this profession, I knew the commitment implied risk. And although I put myself in danger, I feel like the grateful one.

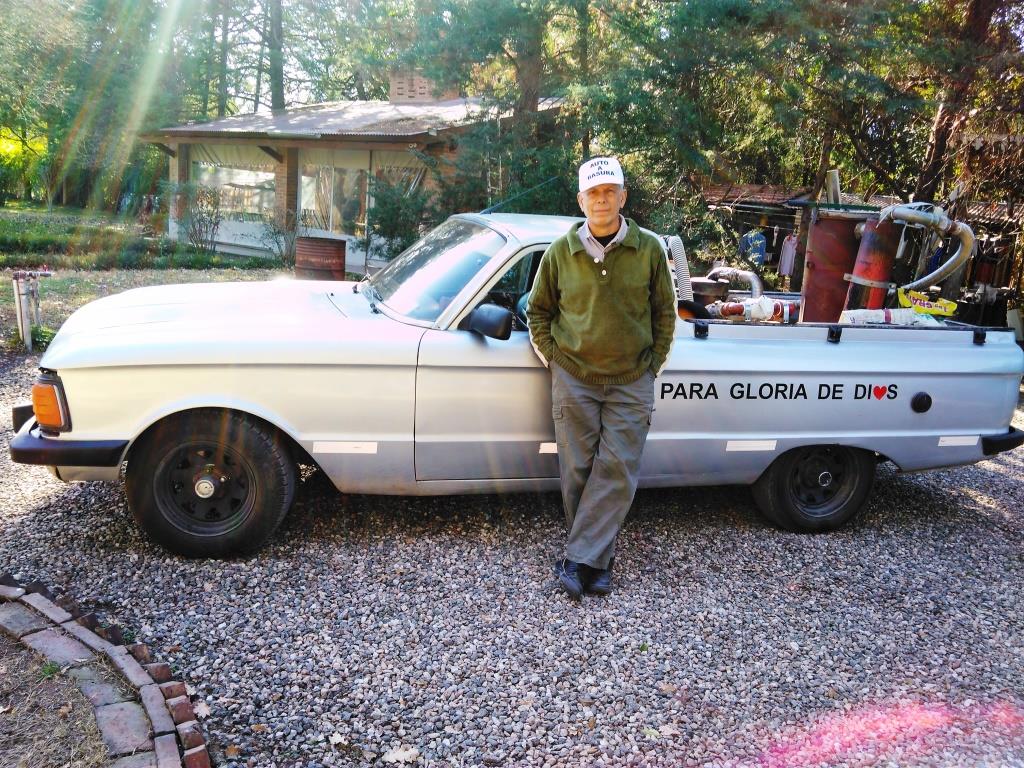

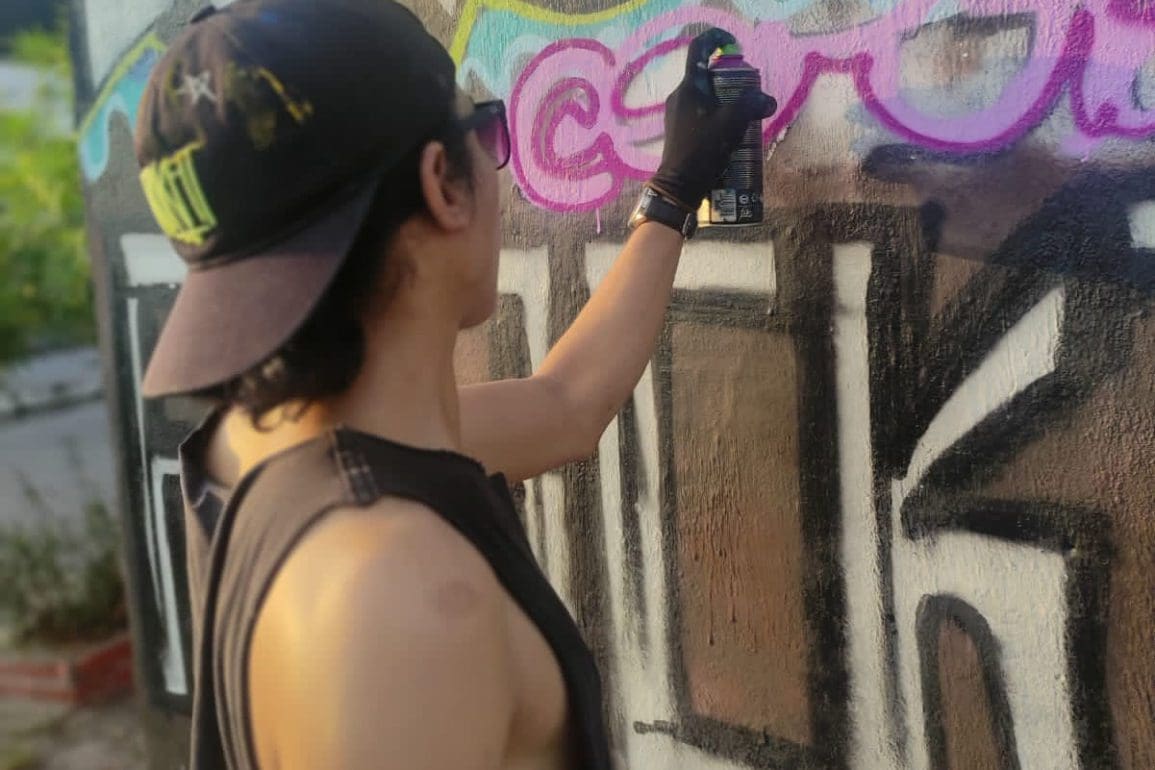

All photos courtesy of Pedro Paczkowski.