Man sexually abused by Catholic priest in Argentina fights back

At the table in a small bar, I spoke for three hours with [the journalist]. I did not look around nor see or hear other people. My world became reduced to that table where I brought to light a story I hid for more than 30 years. For the first time, I said out loud and in public that Walter Avanzini sexually abused me.

- 4 years ago

July 17, 2022

CORDOBA, Argentina ꟷ It was a Saturday unlike any other. I decided to tell my children about the abuse I endured from a Catholic priest as a teenager.

I approached my son Pablo’s room and knocked on the door before entering. He sat at his desk in front of his computer. Posters of sports teams surrounded us. Perched on his bed I blurted out, “Did you see what happened to Agus’ friend?”

Two things prompted me to tell my story at last. I felt shocked when television coverage revealed that actor Juan Darthes abused fellow actress Thelma Fardin. At the same time, my daughter Agustina had been supporting her friend who experienced abuse.

In Pablo’s room I added, “I understand [Agus’ friend] because it happened to me.”

He shares his story with his children before going public

To support someone, we often say “I understand how you feel.” This time, I knew exactly the feelings these women endured. I decided not only to tell my story to my children, but also to the world.

Looking into Pablo’s eyes, I continued. I can always see what he feels and whether he understands me or not. The same is true with my students when I teach, but this was my son. What I said – what I shared with him – in some way influenced the lives of my entire family.

I spoke quietly without crying or hesitating. In that moment I felt like a determined man. I will do this now, I thought, then decide how best to move forward.

Pablo reacted calmly. He looked worried but did not lose his temper. His releasing of those emotions would come later, on social networks, when he accompanied me on interviews, and in the trial I initiated.

I finished talking to Pablo and crossed the entire house. I reached the second living room we built when we expanded. My daughter sat next to her mom. She saw me walk in and knew immediately this would be a different kind of talk.

She made I face I saw before when we talked about something serious. We all shared social views that leaned left and would frequently speak about politics and issues that were important to us. This time, however, was different. She did not expect me to share what I did.

Agustina absorbed my story quickly [about being abused by a Catholic priest]. She became emotional and hugged me. While not easy for her, young people today seem increasingly prepared for these things. They are predisposed to this kind of abuse which went unsuspected by the youth of my generation.

Priest repeatedly calls boy into his room

I never even knew these things happened to people. Today’s youth assume these acts occur and support one another differently. That helped me.

Two or three days later, as is often the case, the emotional release came. Everything I held inside came out. Alone, in the shower, I broke down. Crying, I remembered what I endured. A few moments later, I returned to my normal state.

Perhaps it is a defense mechanism to experience delayed feelings briefly that way. It has happened many times. Sharing my testimony stirs up the story and a couple days later, I realize the impact of speaking, and I cry. The night of my abuse haunts me.

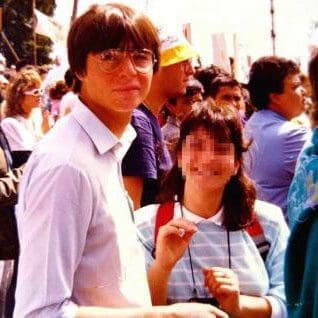

In 1986, at 17 years old, I attended a seminar in the Diocese of Río Cuarto, in the province of Córdoba. The Catholic priest in charge, Walter Avanzini, grew close to me. One night, he called me into his room. It seemed normal. Soon after entering, I instantly realized what was happening was wrong.

It took longer to understand he made me a victim not an accomplice. When he began to abuse me, I became completely paralyzed. Surprise prevented me from reacting. “This can’t be happening; it’s not real,” I thought.

I could not process the first night of abuse and could not refuse to return to his room. It repeated the following night. I have no way to explain the feeling which prevented me from reacting, despite being aware of what was happening.

It seems easy to ask, “Why didn’t you just run away?” I do not know. I’ll never know, but I could not react nor escape.

Parents find out, abuse ignored by the Church

What happened in that room, I wish I could erase from my memory. My abuser once told me, “When you say [in confession] what we did, do not use my name.” What “we” did, he said. For years I thought we did something. Today, I understand I did nothing.

Guilt and shame embedded themselves inside me. Three or four years passed before I spoke about it. The first people I told included some nuns (one of whom is my life partner today) and my older brother who served as a priest. I had entered seminary but left. I could not take it any longer and needed to let my story out.

Later, I talked to my parents, though it proved difficult. My mother lived with one lung, arthritis, and osteoarthritis. Her delicate health worsened after I shared what happened to me. My parents could not understand why I left seminary so one day, I sat them down and we talked. I cried a lot. In fact, we all cried. The moment, while extremely sensitive, felt liberating.

I began noticing the complicit nature of the Church when my father told a priest friend of the family. He served as the parish priest in the town of Canals and traveled to Río Cuarto to ask the bishop to take Avanzini away for a while.

I found out that internally, Avanzini was a known pedophile. Another priest with a similar background also became ordained. With Avanzini, the Church gave him six months to “recover.”

Priest resurfaces, young man faces fallout from his trauma

I had an insider experience of the Church which offered me an advantage – a true and objective perspective. In a sense, I lived inside the church, even though I was alienated from it. Looking back, I wish I never met so many nefarious characters there, but I did. I knew about their actions, and I became a victim.

Since I was a teenager, I heard nothing more of Avanzini until 1998. In between the time of my abuse and his reappearance in my life, I went on missions to Africa and Nicaragua. One day, I turned on the television to see my abuser in a report on child prostitution. He appeared in the images with the clients of the prostitution ring.

The community quickly protested against him, and I joined, although I still had not publicly told my story. After my dad reported it, Avanzini never stopped being part of the Church or having contact with minors.

In the years following the abuse, I thought I led a normal life, yet something seemed wrong. My relationships with women felt abnormal. In a relationship with my current partner, living together, the first consequences appeared. I suffered from erectile dysfunction.

A psychologist I felt close to helped me. When I told her what happened to me in Río Cuarto, almost instantly, I resumed sexual relations with no problem.

That session proved enough in the moment, but years passed before I spoke again. Talking about my abuse unlocked deeper issues.

Journalist details the story of priest’s crimes

Between 2018 and 2019 the final breaking point occurred, and with it, the end of my silence. When I told my children what happened to me, I simultaneously approached the Survivors Network of Ecclesiastical Abuse, an organization that advises and accompanies victims.

I read some newspaper articles linked to my case about a former nun and member of the Network. Another story came out from two priests who got married. Journalist Lisandro Tosello wrote both stories. I sent him a note to propose he interview me, and he accepted.

At the table in a small bar at the university in the capital city of Córdoba, I spoke for three hours with Lisandro. I did not look around nor see or hear other people. My world became reduced to that table where I brought to light a story I hid for more than 30 years. For the first time, I said out loud and in public that Walter Avanzini sexually abused me. I could not help but to cry.

When I finished telling Lisandro everything, I felt the accumulated tension in my body and the weight of my story. To this day, when I pass that bar, I think, “This is where it all started.” At that time, in that place, I became a public figure – a reference in the fight for justice.

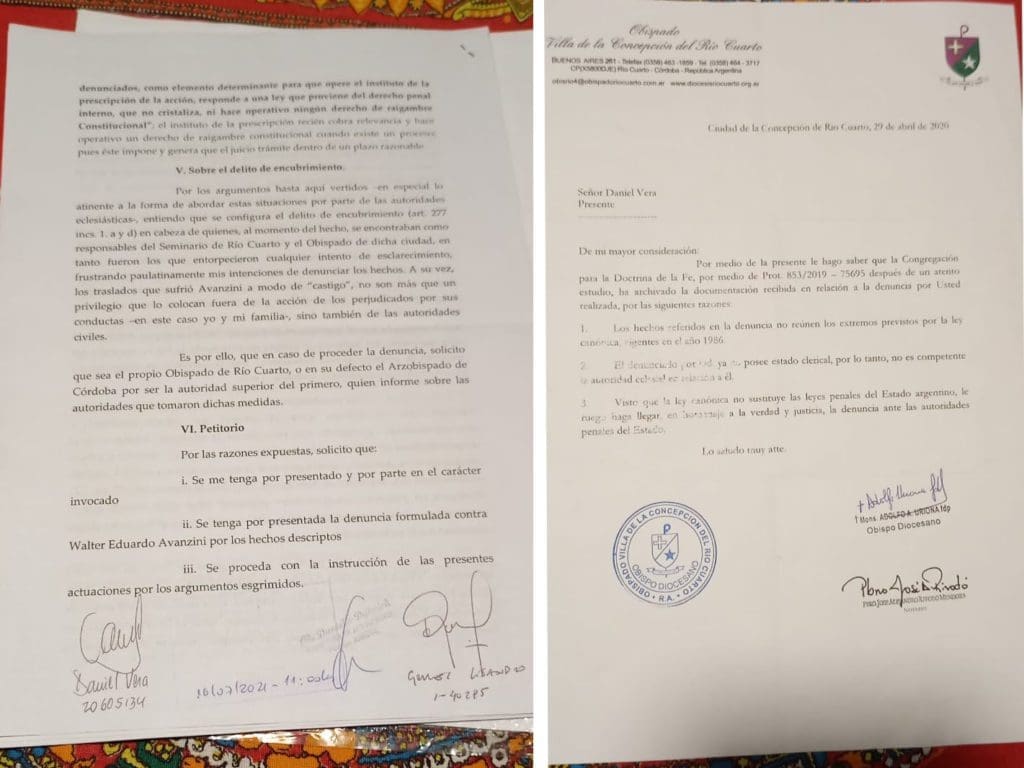

On the advice of the Network’s lawyer, I moved forward with an ecclesiastical complaint and a criminal complaint. What came next proved one of the most horrible things I can remember and one of the most difficult moments for me.

Story of priest abuse breaks, repercussions ensue

On Sunday, June 2, 2019, I walked to the newsstand in my neighborhood knowing my interview would appear in La Voz del Interior – the most traditional newspaper in the province of Córdoba.

Surprise filled me when I discovered not only my story in the newspaper, but my photo at the top of the cover page. I felt naked, as if the entire world knew my story and knew me. Though I sought out the opportunity, I did not anticipate it. The first thought to cross my mind became, “What did I do?”

I went home hoping to see no one. The first message arrived on my cell phone. A classmate of mine sent a photo from the newspaper and a message, “Today, I woke up brave.” In the photo, you can see me standing in front of the seminary where Avanzini studied, now the Catholic Institute.

Then the reproaches began, mainly toward the journalist. The repercussions only served to confirm we made the right choice. The entire week became a chaotic disaster full of calls, messages, encouragement, support, and requests for interviews.

Though I sought it out, I felt unaccustomed to the attention. Sometimes, I could speak. Other times, my emotions got in the way and prevented it.

Loss of family and a voice for the victims

Going public pushed me away from my brother and father who both serve as Catholic priests. It felt like they never took my side. In January of this year, after decades, I finally sat down with my dad and asked him why he never stood up for me. He simply rested his shoulders.

The next time I saw my father, I went to the parish where he worked. I felt afraid to be in a place like that, one so much like the place I experienced abuse. My life partner joined me which gave me strength in the moment. Though I did not want to be there, it wasn’t bad, and I felt comfortable.

A mix of sadness and anger lingered after. I feel sad about the relationship I have today with my dad – a broken relationship. My father, an old man, represents the church hierarchy which I condemn. They remain complicit in what happened to me and so many others. As a result, I face a dilemma. I reject the church and its religious manifestations.

Since going public, I became an example for others. I give interviews and serve as a spokesperson for my organization. As a consequence, many people think of me simply as “the man who was abused.” I want to be seen as more than what happened to me. I am not reduced to that moment.

Victims of abuse bare a scar they may never erase. It remains with you and reminds you of what you experienced, though it is not a physical scar. We accept it and learn to deal with it so it cannot ruin our lives.

I no longer find my scar ugly. I live with it. Not telling my story ruined my early life. I do not enjoy talking about my story. It tires me, but I do it for the people I know and those I do not know who can benefit from my testimony and my fight.

I never hesitate. What I do today remains important. I do what I have to do.